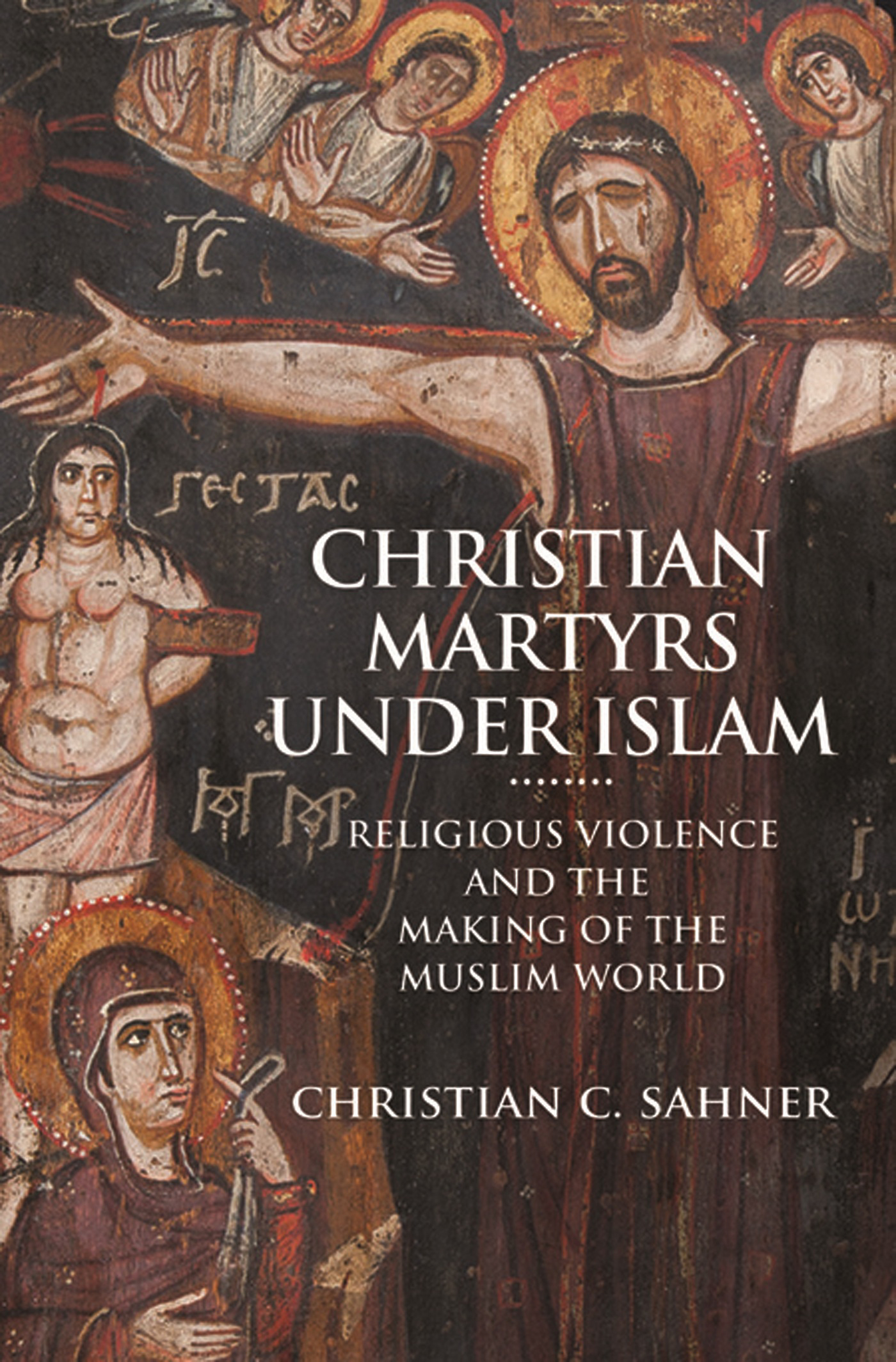

Christian Martyrs under Islam

Christian Martyrs under Islam

Christian Martyrs under Islam

Christian Martyrs under Islam

RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE

AND THE MAKING OF THE MUSLIM WORLD

Christian C. Sahner

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton & Oxford

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-17910-0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017956010

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Fred Appel and Thalia Leaf

Production Editorial: Debbie Tegarden

Text Design: Leslie Flis

Jacket Design: Leslie Flis

Jacket art: Crucifixion with Two Thieves, by permission of Saint Catharines Monastery, Sinai, Egypt. Photograph courtesy of Michigan-Princeton-Alexandria Expeditions to Mount Sinai

Production: Jacquie Poirier

Publicity: Katie Lewis

Copyeditor: Elisabeth Graves

This book has been composed in Miller

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For my parents.

[Jesus said to the crowd:] But before all this occurs, they will arrest and persecute you, delivering you over to synagogues and prisons, and they will have you led before kings and governors because of my name. This will be the time for you to testify. Remember, you are not to prepare your defense beforehand, for I myself shall give you a mouth and a wisdom, which none of your opponents will be able to resist or refute. You will be betrayed even by parents, brothers, kinsmen, and friends, and they will put some of you to death. You will be hated by all because of my name, but not a hair on your head will perish. By your perseverance you will gain your souls.

Luke 21:1219

Do not call those who are slain in the way of God dead. Nay, they are living, only you perceive it not.

Quran al-Baqara 2:154

Contents

Contents

Preface

Preface

Some readers may open this book seeking answers about the tumult that currently roils the Middle East. I hope that it is interesting and useful for them. My goal, however, has never been to write a history that connects past and present. Indeed, aside from these brief words of introduction (and a few scattered thoughts in the conclusion), this book does not engage in comparisons between religious violence in the early Islamic era and violence today. Such comparisons are legitimateas much for the similarities they reveal as the differences. But that is an exercise best left to another writer for another time.

Research on this book started in 2011, just as the movement of popular protest known as the Arab Spring was beginning to sweep across the region. In the years since, this moment of optimism has given way to political bedlam and sectarian conflict. Especially notable has been the rise of the Islamic State and its persecution of ancient Christian communities and other minorities in Syria and Iraq. To watch these events unfold has been to hear distant echoes of a medieval world I encountered through my research: mass enslavement, burdensome taxes, forced conversions, crucifixions, and still worse. Although the Islamic State alleged to revive the traditions of the early caliphate, it was clear that it often misinterpreted, exaggerated, and twisted these to suit its modern agenda. I also observed Christians reviving the practices of their early medieval forebears, venerating the victims of recent religious violence as saints and martyrs.

It is important to acknowledge these symbolic parallels up front. At the same time, this book aspires to tell another story: to provide the first comprehensive history of Christian martyrdom in the formative centuries after the rise of Islam, a phenomenon that is largely unknown to the public as well as many academic specialists. More broadly, it aims to explore how violence configured relations between the early Muslims and their Christian subjects, the role that coercion and bloodshed did or did not play in the initial spread of Islam, and the manner in which Christians came to see themselves as a beleaguered minority in the new Muslim cosmos. These are central questions for the study of early Islam and Middle Eastern Christianity more broadly, yet finding clear answers to them can be surprisingly difficult.

In the pages to come, I suspect that readers of all religious and political stripes will find some points to cheer and others to contest. As a historian, my only goal is to represent the past as accurately as possible, not on the basis of personal conviction but on reasoned analysis and balanced treatment of the evidence. I will consider this book a success if it manages to spur others to learn more about the rich history of Middle Eastern Christians, especially their relationship with Muslims. In these troubled times, it is necessary to remember that peace has defined this relationship across the ages to a much greater extent than bloodshed.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This book began as a doctoral dissertation in the Department of History at Princeton University. While there, I could not have asked for better advisers than Peter Brown and Michael Cook, fine scholars and even finer mentors. In addition to shepherding the thesis to completion, they read and critiqued drafts of the revised book manuscript. John Haldon and Robert Hoyland assessed the original dissertation and have provided support ever since.

Garth Fowden, Elizabeth Key Fowden, Luke Yarbrough, and two anonymous reviewers from Princeton University Press read drafts of the entire book, saving me from countless errors and proposing changes that clarified my own muddled thoughts. Uriel Simonsohn read appeared in the Journal of the American Oriental Society 136 (2016), which is reproduced here with the generous consent of the editors.

I would like to acknowledge the following teachers and colleagues who contributed to the completion of this book in ways both big and small: Sean Anthony, David Bertaina, Andr Binggeli, Betsy Brown, the late Patricia Crone, the late Slobodan uri, the late Robert Gabriel, George Kiraz, Mustafa Mahfuz, Emmanuel Papoutsakis, Helmut Reimitz, Michael Reynolds, Peter Sarris, John Slight, Stephen Shoemaker, Kenneth Wolf, and Fritz Zimmermann. Various individuals helped me procure photos, and they are gratefully acknowledged in the captions. I would especially like to thank Fr. Justin Sinaites for obtaining high-resolution photos from St. Catherines Monastery, Mt. Sinai. Thanks go to Shane Kelley for producing the fine maps.

Over the years, my research benefited from the support of the following academic institutions: in Oxford, the Rhodes Trust; in Princeton, the Department of History, the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, the Group for the Study of Late Antiquity, the Center for the Study of Religion, and the Program in Near Eastern Studies in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Education; in Beirut, the Institut franais du Proche-Orient; in Amman, the American Center for Oriental Research; and in New York, the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation. I would especially like to thank the Master and Fellows of St Johns College, Cambridge, where I spent two blissful years as a research fellow, with ample time to complete this project and explore new ones. I am also grateful for the support of my new colleagues in the Faculty of Oriental Studies and St Cross College, Oxford. Thanks also go to Fred Appel, Debbie Tegarden, Elisabeth A. Graves, and the staff of Princeton University Press for expertly guiding this book to publication.

Next page

Christian Martyrs under Islam

Christian Martyrs under Islam