Transcriber's Note:

Minor typographical errors have been corrected without note. Significant changes have been listed at the end of the text. Archaic, dialect, variant and quoted spellings remain as printed. Inconsistent hyphenation has been made consistent except when used for emphasis or within quotations.

BYGONE PUNISHMENTS.

Works by William Andrews.

Mr. Andrews' books are always interesting.Church Bells.

No student of Mr. Andrews' books can be a dull after-dinner speaker, for his writings are full of curious out-of-the-way information and good stories.Birmingham Daily Gazette.

England in the Days of Old.

A most delightful work.Leeds Mercury.

A valuable contribution to archological lore.Chester Courant.

It is of much value as a book of reference, and it should find its way into the library of every student of history and folk-lore.Norfolk Chronicle.

Mr. Andrews has the true art of narration, and contrives to give us the results of his learning with considerable freshness of style, whilst his subjects are always interesting and picturesque.Manchester Courier.

Literary Byways.

An interesting volume.Church Bells.

A readable volume about authors and books.... Like Mr. Andrews' other works, the book shews wide, out-of-the-way reading.Glasgow Herald.

Turn where you will, there is entertainment and information in this book.Birmingham Daily Gazette.

An entertaining volume.... No matter where the book is opened the reader will find some amusing and instructive matter.Dundee Advertiser.

The Church Treasury of History, Custom, Folk-Lore, etc.

It is a work that will prove interesting to the clergy and churchmen generally, and to all others who have an antiquarian turn of mind, or like to be regaled occasionally by reading old-world customs and anecdotes.Church Family Newspaper.

Mr. Andrews has given us some excellent volumes of Church lore, but none quite so good as this. The subjects are well chosen. They are treated brightly, and with considerable detail, and they are well illustrated. The volume is full of information, well and pleasantly put.London Quarterly Review.

Those who seek information regarding curious and quaint relics or customs will find much to interest them in this book. The illustrations are good.Publishers' Circular.

Curious Church Customs.

A thoroughly excellent volume.Publishers' Circular.

We are indebted to Mr. Andrews for an invaluable addition to our library of folk-lore and we do not think that many who take it up will slip a single page.Dundee Advertiser.

Very interesting.To-Day.

Mr. Andrews is too practised an historian not to have made the most of his subject.Review of Reviews.

A handsomely got up and interesting volume.The Fireside.

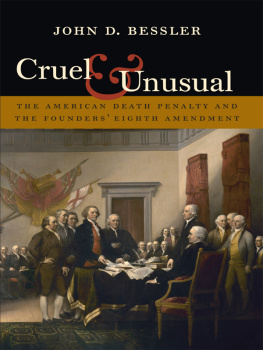

TITUS OATES IN THE PILLORY.

(From a Contemporary Print.)

Bygone ...

Punishments.

Preface.

About twenty-five years ago I commenced investigating the history of obsolete punishments, and the result of my studies first appeared in the newspapers and magazines. In 1881 was issued "Punishments in the Olden Time," and in 1890 was published "Old Time Punishments": both works were well received by the press and the public, quickly passing out of print, and are not now easily obtainable. I contributed in 1894 to the Rev. Canon Erskine Clarke's popular monthly, the Parish Magazine, a series of papers entitled "Public Punishments of the Past." The foregoing have been made the foundation of the present volume; in nearly every instance I have re-written the articles, and provided additional chapters. This work is given to the public as my final production on this subject, and I trust it may receive a welcome similar to that accorded to my other books, and throw fresh light on some of the lesser known byways of history.

William Andrews.

The Hull Press,

August 11th, 1898.

[1]

Bygone Punishments.

Hanging.

T

he usual mode of capital punishment in England for many centuries has been, and still is, hanging. Other means of execution have been exercised, but none have been so general as death at the hands of the hangman. In the Middle Ages every town, abbey, and nearly all the more important manorial lords had the right of hanging, and the gallows was to be seen almost everywhere.

Representatives of the church often possessed rights in respect to the gallows and its victims. William the Conqueror invested the Abbot of Battle Abbey with authority to save the life of any malefactor he might find about to be executed, and whose life he wished to spare. In the days of Edward I. the Abbot of Peterborough set up a [2] gallows at Collingham, Nottinghamshire, and hanged thereon a thief. This proceeding came under the notice of the Bishop of Lincoln, who, with considerable warmth of temper, declared the Abbot had usurped his rights, since he held from the king's predecessors the liberty of the Wapentake of Collingham and the right of executing criminals. The Abbot declared that Henry III. had given him and his successors "Infangthefe and Utfangthefe in all his hundreds and demesnes." After investigation it was decided that the Abbot was in the wrong, and he was directed to take down the gallows he had erected. One, and perhaps the chief reason of the prelate being so particular to retain his privileges was on account of its entitling him to the chattels of the condemned man.

Little regard was paid for human life in the reign of Edward I. In the year 1279, not fewer than two hundred and eighty Jews were hanged for clipping coin, a crime which has brought many to the gallows. The following historic story shows how slight an offence led to death in this monarch's time. In 1285, at the solicitation of Quivil, the Bishop of Exeter, Edward I. visited Exeter to enquire into the circumstances relating [3] to the assassination of Walter Lichdale, a precentor of the cathedral, who had been killed one day when returning from matins. The murderer made his escape during the night and could not be found. The Mayor, Alfred Dunport, who had held the office on eight occasions, and the porter of the Southgate, were both tried and found guilty of a neglect of duty in omitting to fasten the town gate, by which means the murderer escaped from the hands of justice. Both men were condemned to death, and afterwards executed. The unfortunate mayor and porter had not anything to do with the death of the precentor, their only crime being that of not closing the city gate at night, a truly hard fate for neglect of duty.