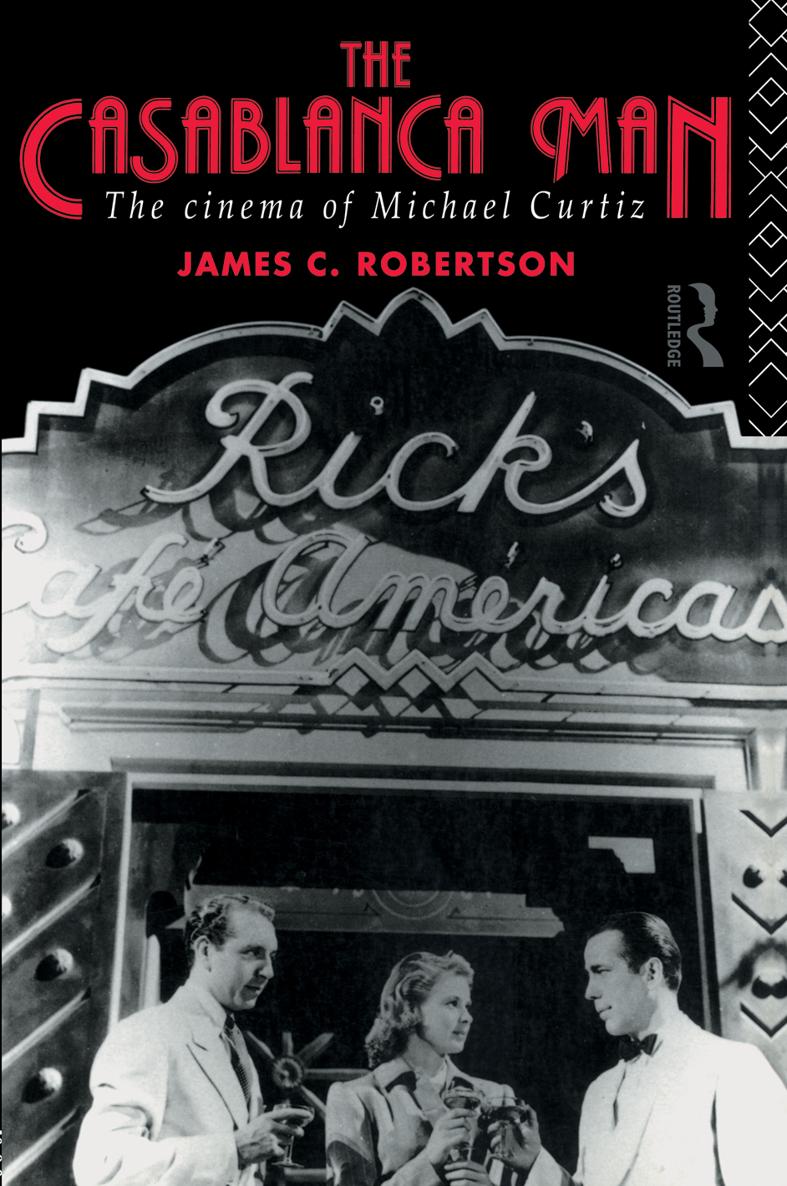

THE CASABLANCA MAN

The cinema of Michael Curtiz

James C. Robertson

First published 1993

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Paperback edition published 1994

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2008

1993, 1994 James C. Robertson

Phototypeset in 10/12 pt Times by Intype, London

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Robertson, James C.

The Casablanca Man: The cinema of Michael Curtiz

New edition I. Title

791.430233092

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Applied for

ISBN 0415115779

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent.

CONTENTS

Michael Curtiz discusses Mission to Moscow with Joseph E. Davies and Walter Huston

Harry M. Warner, Joan Crawford, Jack L. Warner, and Michael Curtiz

Curtiz talking to Juano Hernandezs son

Michael Curtiz in pensive mood while preparing for Jim Thorpe All American

Elvis Presley and Curtiz in earnest conversation on the set of King Creole

Spencer Tracy bids a grim farewell to Bette Davis in 20,000 Years in Sing Sing

Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Ian Hunter in a scene from The Adventures of Robin Hood

James Cagney as George M. Cohan in Yankee Doodle Dandy

In the Paris railway station scene from Casablanca, Humphrey Bogart receives bad news from Dooley Wilson

Claude Rains as Captain Louis Renault in the famous climactic airport scene from Casablanca

Manart Kippen as Stalin in Mission to Moscow

Zachary Scott, Jack Carson, and Joan Crawford discuss business in Mildred Pierce

John Garfield shoots Victor Sen Yung in The Breaking Point (1950)

Like all authors, I am indebted to many people, not least to Michael Curtiz himself for my enjoyment of his films over the past half century. This book owed much to a very generous award from the British Academy which enabled me to conduct research at the University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles and at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills. At USC Leith Adams and Stuart Ng, the Warner Brothers archivists, and Ned Comstock in the Department of Special Collections were unsparing in their efforts to assist me and drew my attention to vital material I should otherwise have missed. I am truly grateful to them not only for their professional expertise, without which this work would be the poorer, but also for their personal kindnesses which made my visit to Los Angeles so memorable and informative beyond the subject research concerned. Samuel Gill at the Margaret Herrick Library also placed useful material in my path. My gratitude is also due to The Scarecrow Press and to Warner Brothers for permission to quote from material to which they own the copyright. The film stills are reproduced by courtesy of the National Film Archive Stills Division and of the film companies involved. The staffs of the British Film Institute Library, the USC Cinema-Television School Library, the Margaret Herrick Library, and the National Film Archive Stills Division never failed to meet my many requests for research material with unfailing cheerfulness. Finally, my editors, Rebecca Barden and her predecessor Helena Reckitt, were encouraging and provided me with much moral support.

HUAC | House Un-American Activities Committee |

IRA | Irish Republican Army |

MGM | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

OWI | Office of War Information |

TCF | Twentieth Century-Fox |

USC | University of Southern California |

For just over half a century the author has been an incurable but inexpert film fan whom Yankee Doodle Dandy, Casablanca, and Mildred Pierce much impressed when as a boy in his early teens he first saw them in the 1940s. As an adult he has seen each of them again many times, initial wonderment being gradually transformed into a fascination extending to other post1945 films of Hungarian-born director Michael Curtiz as well as to some of Curtizs earlier works which he had been too young to see upon their original release. Puzzled in later life as to why a director who could turn out such outstanding films remained comparatively unrecognized relative to other eminent contemporary Hollywood directors, he at length set out to discover as much about Curtiz and his films as possible.

Nowadays Curtiz is best known for the superb Casablanca, for a handful of other 1930s and 1940s features, for his genre versatility, for his fractured English, and for his verbal abuse of players. However, there was clearly much more to his career than all this, for his overall output from 1912 to 1961 remains one of the highest in cinema history. More than two-thirds of his approximately 160 films were made outside his own country, while about half of them were sound movies not in his native tongue. This of itself ranks as a considerable achievement even if all his films had been mediocre, but in fact some like Captain Blood (1935), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), and Angels With Dirty Faces (1938) as well as the three 1940s films already mentioned are acknowledged classics of their various genres and many others are of well above average quality. Yet at Curtizs death in 1962, when the cinema was in manifest decline, he was accorded little more than token recognition.

At that time an academic debate was in full swing between writers who saw the director as the main element, or the auteur, of a film, purveying an identifiable attitude or message, and critics who denied that the directors function was all-important. As early as 1917 in Hungary Curtiz expressed the view that the director acted as the supreme

Thus Curtiz might have been an example for the auteurists to cite in support of their theory. However, because his individualism was hidden from public view and he could not be associated with any one genre, they implicitly regarded him as merely a studio workhorse. This was an interpretation to which his long service for Warners lent surface plausibility. Those who challenged the validity of auteurism, the disciples in varying degrees of distinguished American film critic Robert Warshow who had died in 1955, viewed Curtiz in much the same way since the course of his Hollywood career seemed to confirm the accuracy of their general approach.

The disagreement over auteurism persists to this day. In Curtizs case neither faction was ready to claim him directly in his immediate