PREFACE

Columbus deserved immortal fame for his courage and indomitable will in pursuing his purpose. His principal accomplishment was his giving mariners the keys to the ocean knowledge of the sailing routes where ships could be blown by prevailing winds across the Atlantic in both directions. As to places where he landed he was confused. To the day of his death he persisted in claiming they were parts of Asia.

That one could reach Asia in less than a month by a voyage westward was the most sensational news that had ever come to Europe. Almost everyone at first believed Columbus. Flushed with wild enthusiasm by the misinformation, eager adventurers went west to tap the wealth of India. All drew blanks. No one could find Asia where Columbus said it was. Something was wrong. Where were the rich cities of China which Marco Polo had visited? Where were the famous ports of India with which the Arabs traded so profitably and which the Portuguese under Vasco da Gama had reached by the long route around the Cape of Good Hope?

Merchants and business men as well as kings wanted to know what lands actually lay on the western side of the Atlantic.

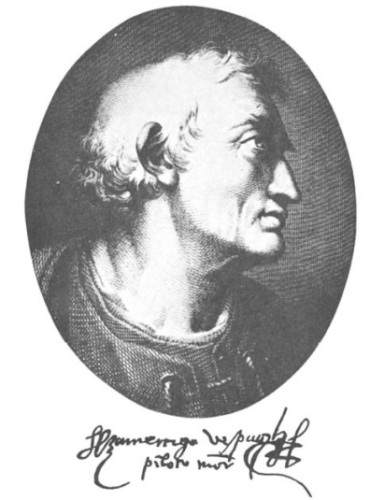

Americo Vespucio, to use the Spanish form of the name Amerigo Vespucci, sailed to the West under the Spanish flag in 1499, with the theory that he might turn a headland into the Indian Ocean. In 1501 he sailed to acquire geographical information for the king of Portugal, who like the Spanish monarch, had been puzzled by the contradictory reports. On his two voyages, Americo discovered the Amazon and Para Rivers, explored over 6,000 miles of continuous shoreline between Venezuela, which he named, and a harbor about 50 South on the coast of Argentina. In 1502 he presented proof of the existence of a hitherto unknown continent, which we may rightly call a New World.

Americo demonstrated that this continent extended too far south to be India. His studies of longitude showed him that its east-west position was thousands of miles from the east coast of Asia, from which it must therefore be separated by another ocean broader than the Atlantic. Americos proofs that there was a new continent which blocked direct westward passage to India, came as a great disappointment to Europeans. But it was verifiable fact.

To say that Columbus discovered America is a subsequent simplification of what actually happened in the drama of falsity and fact throughout which Cristoforo and Americo continued to be good friends.

With a realistic, scientific mind, Americo crossed the Atlantic and found out and reported what was really there. A geographer properly named the new continent America from Americus, the Latin form of the name of the man who discovered it by exploring it. The name was euphonious, in harmony with the names of other continents. It was instantly and forever after on everyones lips.

FREDERICK J. POHL

New York

January 20, 1966

FOREWORD

Two continents are named after Amerigo Vespucci. One-third of the land surface of the globe perpetuates his memory, so that no name in history has a more effective advertising than his, or a wider extension of fame, or a more permanent surety of preservation.

Vespucci has indeed been honored above other explorers, but he has also been vilified by many who have charged him with being an impostor, a charlatan of geography. While some have held that he, by the discovery of America, rendered his own and his countrys name illustrious, there are those who have rejected him, who have denounced him as a boaster, a fame grabber who never commanded a ship, a mountebank who preferred self-contradictions to truth. He has been accused of an unholy ambition to immortalize himself at the expense of Columbus, and he has been sneeringly referred to as an obscure ship chandler. One of the climaxes of vilification was attained by the gentlemanly Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote in English Traits , in 1856: Strange that broad America must wear the name of a thief! Amerigo Vespucci, the pickle-dealer at Seville, who went out in 1499, a subaltern with Hojeda, and whose highest naval rank was boatswains mate, in an expedition that never sailed, managed in this lying world to supplant Columbus, and baptize half the earth with his own dishonest name!

These extremes raise an important issue for inhabitants of the New World. Patriotic pride as well as good sportsmanship impels us to ask whether we have any reason to be ashamed of the origin of the name of our land. Did Amerigo Vespucci discover America, or is the name America an invention based upon false premises, and does it bestow an honor upon the wrong man? The question can be definitely answered, for an impartial study of Vespuccis life and voyages in the light of recent research clears away the cloud of misunderstanding and ignorance by which he has so long been obscured. The investigation will carry its reward, because it is always an exciting mental adventure to follow the mind of a man who perceived the most important fact of his generation before it was seen by anyone else.

The Vespuccian controversy has had a dramatic history. Mundus Novus and the Four Voyages (so-called Soderini Letter) were published in 1504, both purporting to have been written by Vespucci, and both of them were forgeries. The first of the four voyages, dated 1497, gave Vespucci priority of one year over Columbus on the coast of South America and also made him the first explorer of the coastline of Central America, Mexico, and the southeastern coast of the United States.

In 1507 Waldseemiiller first used the name America for the continent of South America, and in 1538 Mercator applied that name to the northern continent. In the middle of the sixteenth century Las Casas attacked Vespucci on legalistic grounds that Columbus had priority, and in 1601 Herrera, accepting the forgeries as genuine, accused Vespucci of falsifying the dates of his voyages.

The three Vespucci letters from Seville, 1500, Cape Verde, 1501, and Lisbon, 1502, were first published as apocryphal, the Seville letter in 1745, the Lisbon letter in 1789, and the Cape Verde letter in 1827.

In 1846 Lester and Foster, in the first biography of Vespucci in English, accepted two of the genuine letters and at the same time uncritically retained the Four Voyages. M. F. Force, in 1879, was the first to suggest that the Four Voyages might be a forgery. In 1895 Harrisse wrote: The four voyages of Americus Vespuccius across the Ocean remain the enigma of the early history of America.

In 1900 Gallois cleared Vespucci of having had anything to do with Waldseemiillers naming of America. The next year Uzielli thought the errors in the Four Voyages were largely due to the lack of an exact text of that narrative. Ober, in 1907, avoided taking sides in the controversy; he held the problem of the first voyage to be insoluble on the basis of the Four Voyages;