Copyright 2016 The Independent Print Limited.

First edition published by Mango Publishing Group.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, file transfer, or other electronic or mechanical means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations included in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses as permitted by copyright law.

This is a work of non-fiction adapted from articles and content by journalists of The Independent and published with permission.

For permission requests, please contact the publisher at:

Mango Publishing Group

2850 Douglas Road, 3rd Floor

Coral Gables, FL 33134 USA

For special orders, quantity sales, course adoptions and corporate sales, please email the publisher at or +1.800.509.4887.

Library of Congress Cataloging

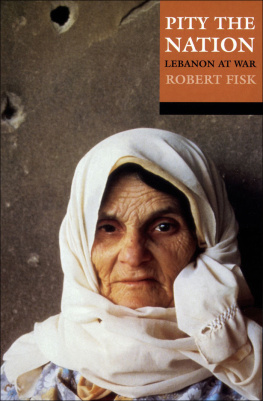

Names: Fisk, Robert; Cockburn, Patrick; Sengupta, Kim

Title: Arab Spring Then and Now / by Robert Fisk, Patrick Cockburn, and Kim Sengupta

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016919560

ISBN 9781633534933 (paperback), ISBN 9781633534926 (eBook)

BISAC Category Code: POL059000 POLITICAL SCIENCE/World/Middle East

Front Cover Image: ValeStock/Shutterstock.com

Back Cover Image: The Independent

ARAB SPRING THEN AND NOWFrom Hope to Despair

ISBN: 978-1-63353-492-6

Printed in the United States of America

"Several experts on the Middle East concur that the Middle East cannot be democratized."

Recep Tayyip Erdogan,

President of Turkey

Editors Note

The wave of demonstrations, protests, riots, coups and civil wars that engulfed North Africa and the Middle East, known as the Arab Spring, was touched off on 17 December 2010 in Tunisia. Bloody civil wars followed in Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen and major uprisings broke out in Bahrain and Egypt. Countries that experienced large and small street demonstrations and protests included Algeria, Iran, Lebanon, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Oman, Sudan, Djibouti, Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Western Sahara, and the Palestinian territories. The initial wave faded by mid-2012, morphing into what some have called Arab Winter large scale conflicts or a return to authoritarianism. Only the Tunisian uprising resulted in a form of constitutional democracy.

This book seeks to capture and contrast events in six countries (Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Bahrain, Yemen, and Syria) during two moments in time THEN (Arab Spring - 2011) and NOW (Arab Winter - 2016). The events are reported and interpreted by three of The Independents distinguished and widely acclaimed foreign affairs journalists who have specialized in coverage of the Middle East for many years Robert Fisk, Patrick Cockburn, and Kim Sengupta.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Saturday, 31 December 2011

ONE MAN WHO CHANGED THE WORLD IN 2011

In truth, Mohammed Bouazizi only survived a few days into 2011. On 4 January, in a coma and swathed in bandages that covered his terrible burns, he died in a hospital near Tunis, aged just 26. He was an ordinary man, just a humble fruit vendor trying to make an honest living and support his family.

On 17 December 2010, however, after one routine petty harassment too many from the authorities, something inside his long-suffering soul snapped. He dowsed himself in petrol and set himself ablaze. In doing so he lit a fire across the Arab world that blazes to this day.

His act of self-immolation stirred protests in his home town of Sidi Bouzid, that quickly spread across all Tunisia. In a bid to save his regime, President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who had ruled the country for the previous 23 years, paid a visit to Bouazizi's bedside a few days before he died. But on 14 January, Ben Ali was swept from power.

The 'Arab Spring' had started. The protests spread first to Egypt, where President Hosni Mubarak would be ousted on 11 February, then to Libya, Yemen, Bahrain and Syria. Some regimes made reforms, some resisted, and some were toppled. But not a single one was unaffected.

Anyone familiar with the Arab world had long known that sooner or later its problems - corrupt regimes that tolerated no independent political movements, feeble economies and mass unemployment in populations in which two-thirds were aged under 25 - would explode. But no one knew when or where the spark would come, still less that it would be provided by Mohammed Bouazizi.

His father died when he was aged three, and though his mother remarried, his stepfather was in poor health and unable to earn. The son attended secondary school, but left to become the main provider for his family, selling fruit and vegetables from a barrow in Sidi Bouzid's market. The young Mohammed was liked by everyone. He was honest and hardworking, trying to give his younger siblings the chance to stay at school. "My sister was the one in university - he would pay for her," his sister Samia said, "and I am still a student and he would spend money on me."

Bouazizi tried to join the army, but was turned down. Efforts to find a regular civilian job met a similar fate. So he was stuck with being a street vendor; every day, he went to the market and bought produce, before pushing his barrow to the local souk. The day's work done, he went back to his family, trying to forget the police who would often make his life a misery because he didn't have the money to bribe them off. And so life went on. Until 17 December, 2010.

That day, he was harassed again, and hauled before a more senior police official, Faida Hamdi, who confiscated his cart and scales. According to Bouazizi's family, either she or her subordinate officers slapped him and insulted his dead father. That this humiliation was directly or indirectly inflicted by a woman only made it worse. He tried to complain to Hamdi's superiors, but they wouldn't see him. Despairing, Bouazizi bought a can of petrol, returned to the municipal building and set himself on fire.

In 17 days, he was dead. The authorities tried to keep the funeral private, but 5,000 people attended. Today, Bouazizi is a symbol of the quest of people throughout the region for human dignity and freedom. The main square in Tunis has been renamed after him; the European Parliament posthumously awarded him its Andrei Sakharov Prize.

The story has not a happy ending. Syria's agony continues, while Egypt's 'caretaker' military has dragged its heels on giving up power; repressive autocracy could yet return in another guise. Back in Sidi Bouzid the mood is sour, too. A few months after his death, Bouazizi's family moved to Tunis, prompting some neighbours to accuse them of turning their backs on their home town, to cash in on their fame. There were even rumours that he hadn't meant to set himself on fire, that he had been drunk.

Nonsense, his friend Mohammed Amri told reporters, almost a year after Bouazizi's death. He was "a serious man who had one dream - to work, buy a car and build a house", he added. Modest goals, but in an Arab world denied them for decades, enough to spur a revolution.