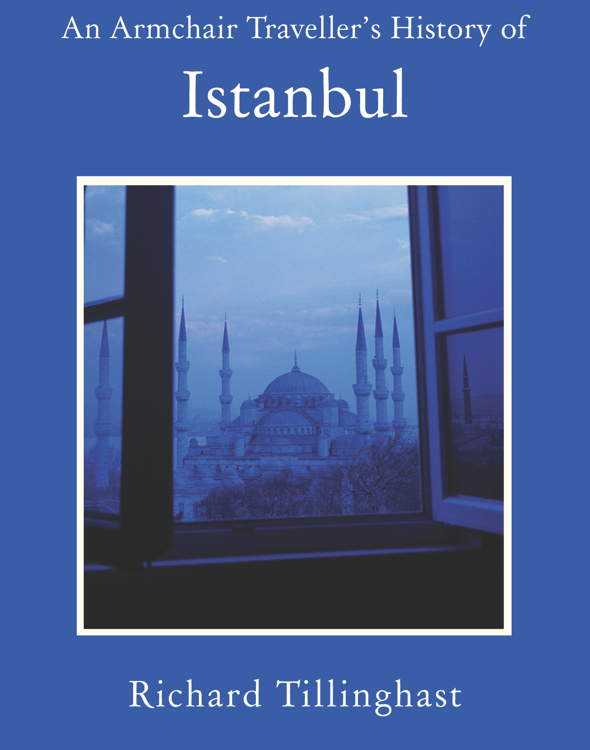

RICHARD TILLINGHAST is a native of Memphis, Tennessee. He first visited Istanbul as editor-in-chief of the travel guide, Lets Go, in the early 1960s. He holds a PhD in English literature from Harvard University and is the author of some fifteen books including Finding Ireland, an introduction to the culture of the country where he lived for a number of years. His 1995 book, Damaged Grandeur, is a critical memoir of the poet Robert Lowell, with whom he studied at Harvard. He has written on travel, books and food for the New York Times, the Washington Post, Harpers Magazine, The Irish Times and other periodicals. His poetry has been published in The New Yorker, the Paris Review and elsewhere; Dedalus Press in Dublin published his Selected Poems in 2009. He has received fellowships and grants from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the Arts Council of Ireland, the British Council and the American Research Institute in Turkey. With his daughter, Julia Clare Tillinghast, he has translated into English selections from the Turkish poet Edip Cansever, collected in a volume called Dirty August. He currently divides his time between the Big Island of Hawaii and the Tennessee mountains.

An Armchair Travellers History of Istanbul

City of Forgetting and Remembering

Richard Tillinghast

Copyright 2012 Richard Tillinghast

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Haus Publishing Ltd

The Armchair Traveller at the bookHaus

70 Cadogan Place, London SW1X 9AH

www.thearmchairtraveller.com

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ebook ISBN 978-1-907822-50-6

Font: DejaVu

Cover illustration: courtesy gettyimages

All rights reserved.

Contents

Part I: Arrival

Part II: Roman and Byzantine Constantinople

Part III: Ottoman Istanbul

Part IV: Modern Istanbul

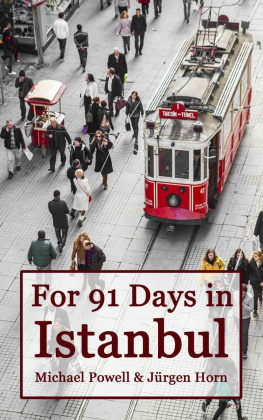

First Impressions

ANYONE WHO KNOWS ISTANBUL will tell you that the best way to arrive in the Queen of Cities is by sea. On my first visit, I came here by boat from Greece. As we steamed up through the Dardanelles, W.B. Yeatss lines came to mind: And therefore I have sailed the seas and come / To the holy city of Byzantium. We docked at Karaky, home in Byzantine days to Genoese sailors. I remember the metallic surfaces that morning, the monotone grey, the harshness of the arrival hall where we disembarked and cleared customs. Istanbul does not present a welcoming face to newcomers perhaps no great city does. It was clear that we were no longer in the Mediterranean, but had entered a climate more Balkan than Aegean, a city that seemed on the face of it to have more in common with Sofia or Belgrade, which were once part of the Ottoman Empire, than with those sun-drenched former seats of empire, Rome and Venice.

Few arrive in Istanbul nowadays the way I did back then. Times have changed; these days I fly like everyone else. And no matter how well I have planned my arrival, in a matter of minutes the city draws me into its own irrational and unpredictable way of doing things. So here I am in the passenger seat of a taxi, no seat belt, with a driver who hurtles through traffic in a way that would never be countenanced in Europe or North America. I have driven in Paris, in Rome, and even in Istanbul itself before the recent population explosion and the coming of the motorways, but I would not care to take the wheel on a road like this.

Lanes mean nothing to my cabbie, who says his name is Osman, nor to anyone else on the road. Because traffic is so congested this Saturday night, Osman drives most of the way on the right-hand shoulder, edging around lorries, weaving in and out among taxis and passenger cars at breakneck speed, sounding his horn almost continuously. We pass a truck with a cargo of onions just visible underneath an old kilim that has been tied down over them. At the edge of the motorway I catch a glimpse of a family of three, huddled in a primordial group on the edge of the road. The man wears black trousers and a white shirt and sports a moustache the generic costume for an urban Turk of a certain class. His wife, wearing a head scarf, holds the baby. What is their story? Why are they standing there at the side of this dangerous highway?

The little family is a fleeting glimpse in the headlong rush of traffic. In Osmans cab the windows are rolled down: we are listening to Turkish arabesk, that haunting music that tells you that this is not Europe, and will never be Europe no matter whether they eventually admit Turkey into the EU or not. I am able to make out some of the words of the song. A man is singing about his father, dead now, a man like a lion, may Allah build him a fine tomb. My driver surprises me by asking my permission to smoke, and I say sure, go ahead, even though I loathe cigarette smoke. I dare not impinge upon the mans sense of who he is.

Osman thumps his chest and proclaims that he is a great driver. I tell him he drives like a lion. He reminds me of the babozuk, or deliba irregulars who fought with the regular Ottoman armies when they captured Constantinople broken-headed or crazy-headed free spirits, as out of control and fear-inducing as the wild cymbal crashes and wailing pipes the army bands played before they attacked. Finally we reach the city and drive along the Golden Horn, absorbed into the great fulcrum of energy that is Istanbul.

Istanbul and Constantinople

A CITY IS A LIVING BEING, with a memory of its own. The more we know of what Istanbul remembers, and even what it tries to forget, the more we enter into its essence. Istanbul has its characteristic sounds ships horns from the Bosphorus, the cries of seagulls, taxis hooting, workmen hammering away at copper and brass in ateliers around the Grand Bazaar, street vendors hawking their wares, and the call to prayer, that haunting recitation one hears five times a day, from before sunrise until after dark, knitting together the hours.

And Istanbul has its smells: lamb kebabs and corn on the cob roasting over charcoal braziers, diesel exhaust from boats and trucks, cigarette smoke, an indefinable aroma of drains from a city with a 2000-year-old sewer system; all of these odours dissolving in the bracing salt air of the sea. On a hot day one is refreshed by the acrid fragrance of fig trees, and the sweet perfume of acacias.

In early autumn, thousands of storks and large birds of prey fly over the city on their annual migration from Europe to Africa. In the spring, on their journey north, they return. The skies are full of them and the creak of their wings as they pass over. Storks are the anarchists of the bird world. They dont line up or form Vs as geese do they straggle all over the sky. For the Persian-Jewish Istanbullu poet Murat Nemet-Nejat in his memoir Istanbul Noir, this migration is an emblem of larger patterns:

Istanbul lies on the multiple migration paths of birds. More than the place where East meets West or Byzantium fuses with Islam, both of which are certainly true, Istanbul is a central location, a point of passage, in a natural movement that has been going on for millions of years, of which the Silk Road is the nearest human reflection. Istanbul has been destroyed and rebuilt, more precisely, re-imagined, innumerable times, creating its history of rich melancholy; but underlying these changes lies a deep, inescapable continuum, experienced just below consciousness. This dialectic between chaos and healing unity is at the heart of the city...