Copyright 2007 by Francisco Goldman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Parts of this work have appeared in

The New Yorker and the New York Review of Books.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

eBook ISBN-13: 978-1-5558-4637-4

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

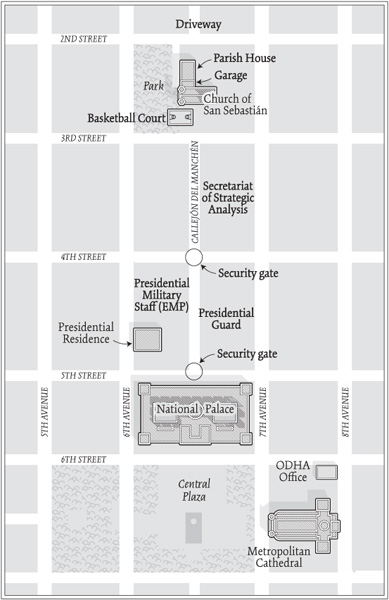

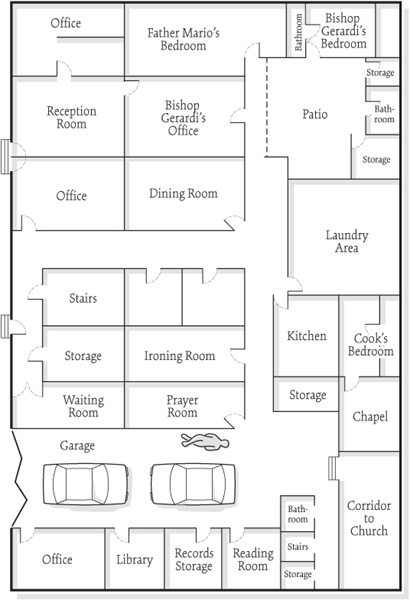

ONE SUNDAY AFTERNOON, a few hours before he was bludgeoned to death in the garage of the parish house of the church of San Sebastin, in the old center of Guatemala City, Bishop Juan Gerardi Conedera was drinking Scotch and telling stories at a small gathering in a friends backyard garden. Bishop Gerardis stories were famously amusing and sometimes off-color. He had a reputation as a chistoso, a joker. In a meeting with him, you would get this whole repertoire of jokes, Father Mario Orantes Njera, the parishs assistant priest, told police investigators two days later. I wish you could have known him. Guatemalans admire someone who can tell chistes. A good chiste is, among other things, a defense against fear, despair, and the loneliness of not daring to speak your mind. In the most tense, uncomfortable, or frightening circumstances, a Guatemalan always seems to come forward with a chiste or two, delivered with an almost formal air, often in a recitative rush of words, the emphasis less in the voice, rarely raised, than in the hand gestures. Even when laughter is forced, it seems like a release.

Guatemalans have long been known for their reserve and secretiveness, even gloominess. Men remoter than mountains was how Wallace Stevens put it in a poem he wrote after visiting alien, point-blank, green and actual Guatemala. Two separate, gravely ceremonious, phantasmagoria-prone cultures, Spanish Catholic and Mayan pagan, shaped the countrys national character, along with centuries of cruelty and isolation. (At the height of the Spanish empire, ships rarely called at Guatemalas coasts, for the land offered little in the way of spoils, especially compared with the gold and silver available in Mexico and South America.) In 1885, a Nicaraguan political exile and writer, Enrique Guzmn, described the country as a vicious, corrupt police state, filled with so many government informers that even the drunks are discreetan observation that has never ceased to be quoted because it has never, from one ruler or government to the next, stopped seeming true.

Bishop Gerardi was a big man, and still robust, though he was seventy-five years old. He was over six feet tall and weighed about 235 pounds. He had a broad chest and back; a prominent, ruddy nose; and thick, curly gray hair. After the murder, his friends recalled not only his sense of humor and affection for alcohol but also his voracious reading, his down-to-earth intelligence, and a nearly clairvoyant understanding of Guatemalas notoriously tangled, corrupt, and lethal politics, which made him by far the most trusted adviser on such matters to his superior, Archbishop Prspero Penados del Barrio, a less worldly figure. Soon after Penados was named archbishop, in 1983, he had recalled Gerardi from political exile in Costa Rica. As the founding director of the Guatemalan Archdioceses Office of Human Rights (Oficina de Derechos Humanos del Arzobispado de Guatemala), which was usually referred to by its acronym, ODHApronounced OH-dahGerardi became one of the Catholic Churchs most important and visible spokesmen and leaders.

The gathering in the garden on that last afternoon of Bishop Gerardis life was a celebration of the completion of Guatemala: Never Again, a four-volume, 1,400-page report on an unprecedented investigation into the disappearances, massacres, murders, torture, and systematic violence that had been inflicted on the population of Guatemala since the beginning of the 1960s, decades during which right-wing military dictators and then military-dominated civilian governments waged war against leftist guerrilla groups. An estimated 200,000 civilians were killed during the war, which formally ended in December 1996 with the signing of a peace agreement monitored by the United Nations. The Guatemalan Army had easily won the war on the battlefield, but making peace with the guerrillas had become a political and economic necessity. Still, the Army was able to dictate many of the terms of the agreement and engineered for itself and for the acquiescent guerrilla organizations a sweeping amnesty from prosecution for war-related crimes. This piata of self-forgiveness was an ominous beginning for an era supposedly based on such democratic values as the rule of law and access to justice, as well as demilitarization.

The peace agreement endorsed a truth commission sponsored by the UNthe Historical Clarification Commissionwhich was intended to establish the history of the crimes of the previous years. But many human rights activists, including Bishop Gerardi, who had participated in the peace negotiations, doubted that the UN commission would be able to provide a thorough accounting of events. The commission was not permitted to identify human rights violators by name or assign responsibility for killings. Testimony given to the commission could not be used for future prosecutions. As a counterweight, under Gerardis guidance, ODHA had initiated a parallel and supportive investigation, the Recovery of Historical Memory Project (Recuperacin de la Memoria Histrica), known as REMHI (REM-hee), which in April 1998 produced Guatemala: Never Again. Bishop Gerardi wrote an introduction to the report.