Contents

Guide

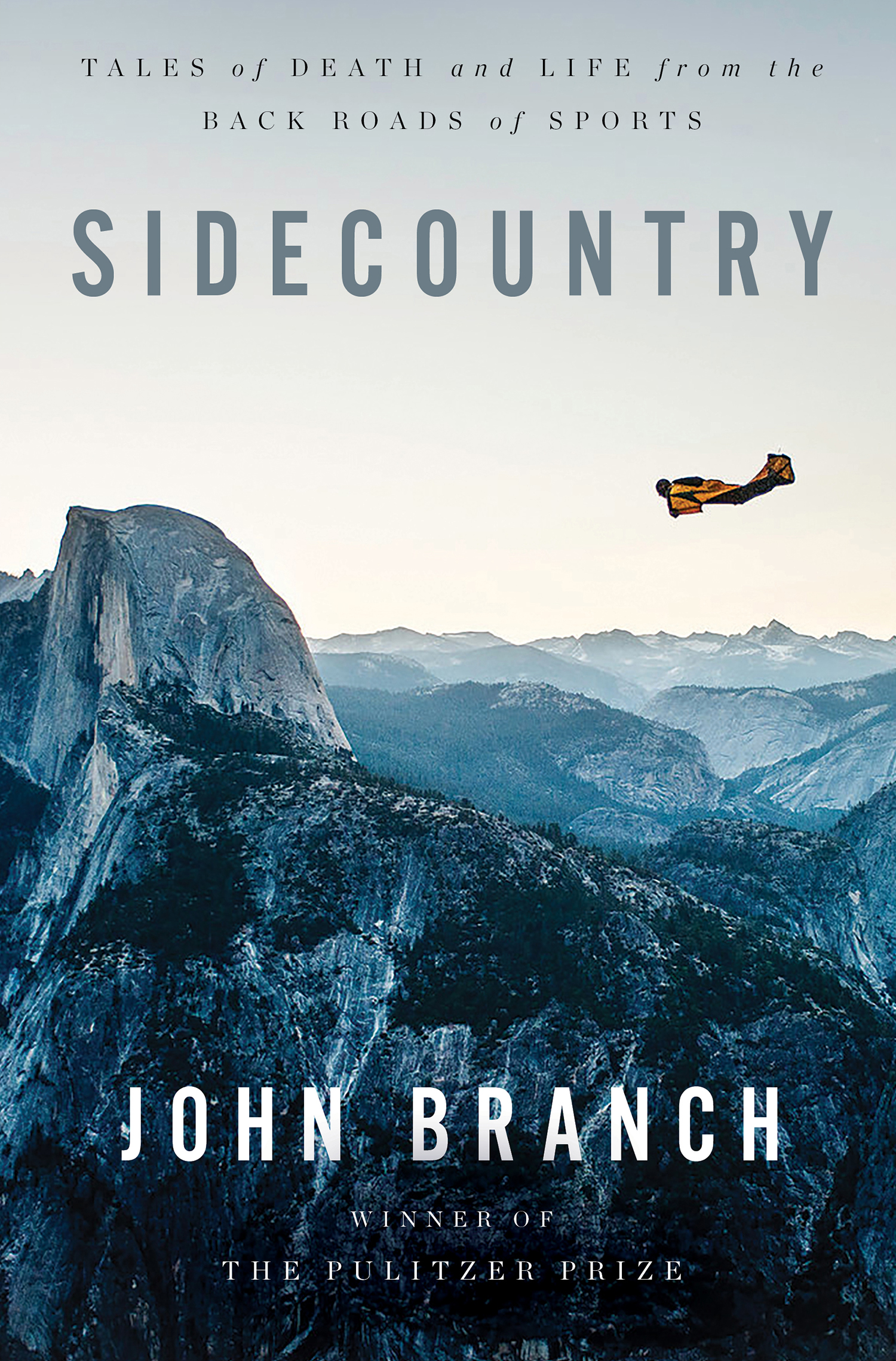

SIDECOUNTRY

Tales of Death and Life from the Back Roads of Sports

JOHN BRANCH

To those daring enough to share their stories with me, in these pages and elsewhere.

CONTENTS

T here was a term that came up a few years ago, when I was reporting what ultimately became a story called Snow Fall, that I had never heard and that I have never forgotten.

Sidecountry.

It is a place just outside the controlled parts of a ski areanot quite the backcountry, but beyond the ropes and wild enough. It seduces the daring with its illusion of safety, thanks to its proximity. It is an adventure within reach, but still out of bounds.

It occurs to me now why I found this word so evocative: it is exactly where I like to go with my reporting and writing. Somewhere on the edges, away from the crowds, exploring worlds known only to a few.

Snow Fall, the first story in this collection, is all about the sidecountry. But so are all the others, in their own way. Theyre just a few steps from the familiar, fresh but imaginable.

When people learn that I am a sports reporter for The New York Times , they invariably ask what sports I cover or what kinds of stories I write.

They imagine that I go to big games, hang around locker rooms and interview renowned athletes. Ive done a lot of that, and still do. But I sometimes go months between games and I dont cover a specific sport.

I dont find people interesting just because theyre famous. I dont find games fascinating just because they have a big audience. I tend to find more meaning in smaller stories.

Im used to the reaction: a mix of doubt and disappointment. Wait a minute what kind of sports reporter are you?

Over the years, Ive settled on this murky explanative shorthand: I try to write stories you didnt know you wanted to read.

In 2020, I covered the death of Kobe Bryanttheres the flicker of name recognition people seem to wantbut the story that stuck with me was not really about him. It was about the pastor and the congregants at the little church near where Bryants helicopter crashed.

The hope is to give readers something different, something unexpected. They would never ask for it, because they wouldnt know to ask. My quest is to provide the unforeseen pleasurealways the best kind.

They dont know that they might want to read a story about a deadly avalanche, or about two climbers hoping to be the first to scale 3,000 feet of famed granite a particular way. No one told them that they might fall for the endlessly losing Lady Jaguars, or the eternally running Hopi boys, or the faithful workers living the last days of a famed horse track. They know nothing of the dead men left high on Mount Everest or their grieving families in India. Maybe theyve never heard of abalone or speedcubing or competitive dog grooming. They would never think to ask me about a girl on my daughters soccer team, no matter what happened to her mother.

My job can feel like a dare: Can I get this story into the New York Times sports section?

These stories are some of my favorite dares. Many dont seem to be about sports at all.

A good number of these are adventure stories. All of them are adventures of the spiritpeople pushing themselves in some way, toward perfection, toward acceptance, toward closure.

That is what all these stories have in commonwhat all good stories have in common: they are about ordinary people tangled in something extraordinary. They are people pushing their own limits, with no quest for fame or money. The people in these stories want to dare, to persist, to brave, to venture, to confront, to believejust because. The rewards are internal. The risks can be real.

We could all imagine ourselves stepping through these gates, whether pulled by adventure or pushed by circumstance.

When reporting Snow Fall, I told people that I was working on a story about an avalanche. I knew that was not quite right. It was about people caught in an avalanche. And if I needed a reminder of the difference, it came on a late spring day, when I went searching for the memory of an avalanche hidden in the emerald green nooks of the Cascade Mountains.

The day before, I had wandered into the woods alone and thought I found it. I came across the bulky end of a snowslide runout, like the fat head of a skinny snake that slinked uphill and out of sight through a thicket of trees and shrubs. The pile was about ten feet tall, maybe forty feet wide.

Somewhere nearby was a stream called Tunnel Creek, heavy with spring runoff. I could hear it. I tried to climb to the top of the snow pile. It was slushy and slick, but there were things to grip and step on, like fir boughs and thick, broken logs and a million pine needles. It was as if the pile had eaten a Christmas tree lot. I could smell the needles and sap. The pile was full of rocks, too. The ice was like Grandmas holiday Jell-O, holding together a salad of pieces frozen inside.

Thats when I realized that an avalanche carries a lot more than snow. It is not the puffy, whooshing plume familiar from videos taken from a distance. At ground level, it is a scouring pad. It is mass times velocity, a force unleashed, usually by humans, that flows downhill on the strict laws of gravity and momentum. It scrubs the earththe vegetation, the rocks, even the animals and people unlucky enough to be in the way.

Like liquid cement, the ice flow hardens when it stops, gripping and suffocating everything inside. Hope for life rests in good fortune or the fast action of rescuers. Otherwise, extraction comes naturally, if at all, in the warming days of spring. That was what I had discovered, alone in the woods one spring day, atop the melting mound of a winter avalanche.

It was weeks before I started writing. It was months before the story had a title. It was a year before it won a Pulitzer Prize.

It was the wrong avalanche.

I learned this the next day, when I returned with a snowboarder named Tim Carlson. He had been one of sixteen people swept up in the stoke of a February morning who formed a loose group that met at the base of nearby Stevens Pass. They took a chairlift up, then another. Once at the upper reaches of the ski area, they took off their skis and boards and hiked through the boundary gate to the summit of a ridge called Cowboy Mountain. Below them was nothing but fresh powder.

This was the sidecountryan adventure within reach, if you dare.

Carlson was there when the group whooped and glided down the steep ravines toward Tunnel Creek. And he was there at the bottom, having lost track of most others by taking another route, when he saw it: a massive pile of snow with a single ski pole sticking out of the top like a flag. His electronic avalanche beacon chirped. He was the first to start digging. He was the first to find a body.

That was winter. Now it was spring.

We didnt make it as far as the avalanche debris pile Id found the day before. Carlson cut uphill before we got there. He led me into a vast meadow, a gentle rise nearly impassable because of thick willows blooming green with spring leaves. The meadow was backed by a steep mountain gouged by what looked like near-vertical ravines shaped by spring runoff. They were like squiggly rain gutters of a giant fortress that stretched thousands of vertical feet into the days low clouds.