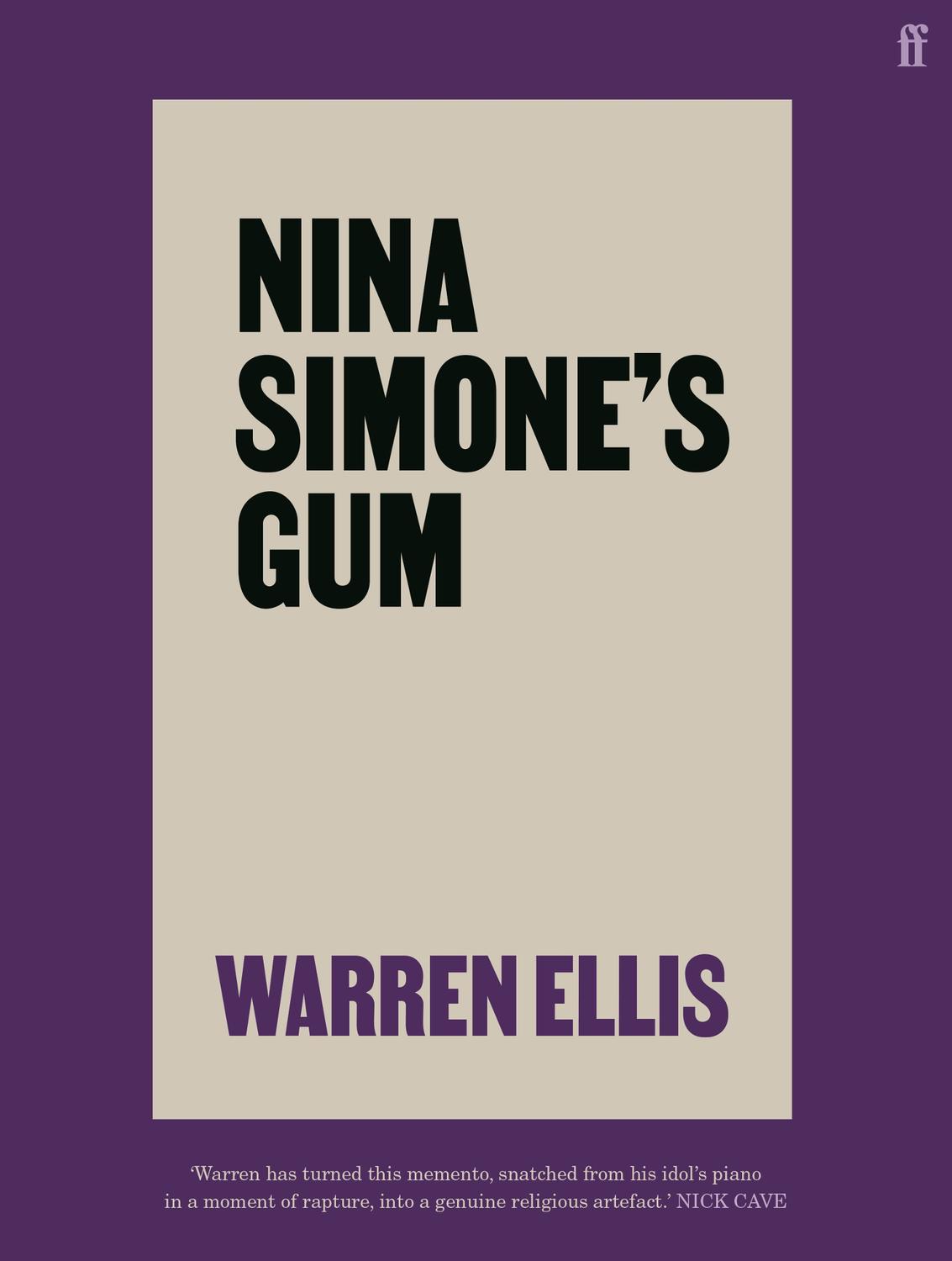

An arm above the last wave.

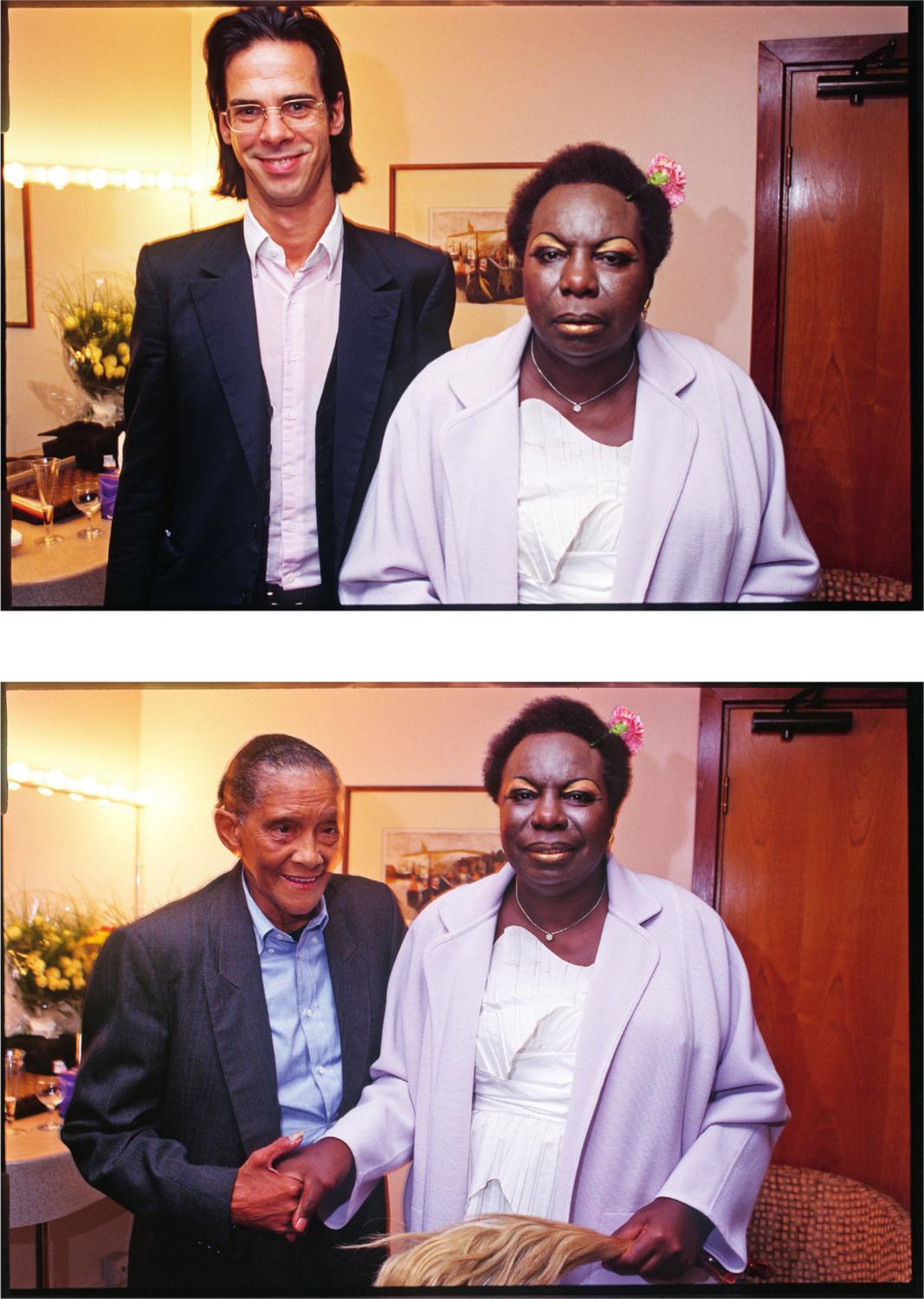

It was 1 July 1999 and I was hanging around backstage at the Meltdown Festival in London. I was the director of the festival that year. It was the Nina Simone evening. Germaine Greer had just come off stage after reading Sappho in the original Greek to a genuinely perplexed audience. Nina Simone was locked in her room and was not seeing anyone. People were running around screaming stuff at me. It was a typical Meltdown evening of genius and barely contained chaos.

Nina Simone was a god to me and to my friends. The great Nina Simone. The legendary Nina Simone. The troublemaker and risk taker who taught us everything we needed to know about the nature of artistic disobedience. She was the real deal, the baddest of them all, and someone was tapping me on the shoulder and telling me that Nina Simone wanted to see me in her dressing-room.

Nina sat in the middle of the dressing-room dressed in a white billowing gown. She wore bizarre metallic gold Cleopatra eye make-up. Pressed against the wall of the room sat several attractive, worried men. She sat, imperious and belligerent, in a wheelchair, drinking champagne. She looked at me with open disdain.

I want you to introduce me! she roared.

Yes, I said.

I am Doctor Nina Simone!

OK, I said.

I knew that I stood within the presence of true greatness, and was happy that, for a small second, I existed within her orbit and that my life would be marked by this moment. I loved her.

I did what she asked and introduced her to the crowd, and then stood in the wings and watched her negotiate the stairs to the stage it was clear that Nina Simone was not well. I watched as she walked slowly, painfully, to the front ofthe stage. She stood ferocious and majestic before her audience, arms at her sides and fists clenched, staring down the crowd. In the audience, five rows back, I could see Warrens face, awestruck and glowing as if from a dream.

Nina Simone sat down at the Steinway. She took a piece of chewing gum from her mouth and stuck it on the piano. She raised her arms above her head and, into the stunned silence, began what was to be the greatest show of my life of our lives savage and transcendent, and the last performance of Ninas in London.

The show ended in mutual rapture and Nina Simone left the stage a different person restored, awakened, transfigured and we too were changed and would never be the same. Not ever. As I turned to leave, Warren was crawling up onto the stage, looking possessed and heading for the Steinway.

Twenty-one years have passed. The piece of chewing gum belonging to Nina Simone, which Warren retrieved from the piano at the Meltdown Festival and rolled up in her hand towel, is being placed on a marble pedestal in a velvet-lined, temperature-controlled viewing box. We are in the Hallway of Gratitude, part of the Stranger Than Kindness exhibition at the Royal Danish Library. As the chief conservator places the little piece of grey gum on the plinth like a hallowed relic, we are all silent, awed.

Warren has kindly released the gum into the world. He has turned this memento, snatched from his idols piano in a moment of rapture, into a genuine religious artefact. It will sit there on its plinth in Copenhagen as thousands of visitors stand before it in wonder. They will marvel at the significance of this most ordinary and disposable of things this humble chewing gum how it could transform, through an infusion of love and attention, into an object of devotion, consecrated by Warrens unrestrained worship, not just of the great Nina Simone, but of the transcendent power of music itself.

The chief conservator of the Royal Danish Library adjusts a small yellow light that shines directly onto the piece of gum, and we all stand back a little, and with held breath, watch it glow.

Nick Cave

1 July 2020

When I was maybe 4 or 5, my older brother Steven, who was 6 or 7, woke me up with his giggling. He was sitting on his bed in front of the window, bathed in light, peering through the crack between the roller blind and the frame. I could only see his outline, backlit by the light, like the shadow scissor-cut out of a facial profile. There was a glowing white light illuminating the window facing the backyard. Light bursting from the space between the roller blind and the window frame.

What is it? I asked.

Come and look.

I went and sat next to him on his bed. He pulled the roller blind away from the frame. The backyard was full of clowns. The sky was full of light. Like a giant flashbulb that flashed for ever. On the lawn was an egg-shaped caravan. It had been converted into a food cart, the window flap held up to make an awning. Inside were clowns making hamburgers. They had a griddle fashioned from corrugated iron to cook the mud patties and would place them between two large gum leaves then pass them to the clowns gathered under the awning. There were clowns everywhere. Smiling and contorting, doing somersaults. Hiding behind trees. Taking aim. Throwing the hamburgers at each other, playing in the large eucalyptus trees near the bedroom window and the crimson bottlebrushes that grew over the wooden back fence. Standing on the top branches of the yellow wattle trees. Scaling trees like cats, hanging upside down with their legs curled around the branches, their clothes covered in mud stains and eucalyptus leaves. They made no noise. Our laughing woke our father in the other bedroom. He asked if everything was OK.

Theres clowns in the backyard! I yelled.

My father replied half asleep from his bedroom, They will be gone in the morning. If they arent, your mother will scare them away when she hangs the washing out on the clothes line.

After some time, my brother and I got tired and fell asleep. We woke in the morning and looked out the window. They were gone. The caravan had vanished. The backyard never looked the same after that.

Every night before bed our father would stand in the doorway of our bedroom with his head bowed, bathed in the amber hallway light, and recite a prayer.

Our Father,

Who art in heaven,

Hallowed be thy name;

Thy kingdom come,

Thy will be done,

On earth as it is in Heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread;

And forgive us our trespasses,

As we forgive those who trespass against us;

Lead us not into temptation,

But deliver us from evil.

For thine is the kingdom,

The power and the glory,

For ever and ever.

God Bless Mummy, Daddy, Steven, Warren and Murray,

All the little girls and boys,

All the doctors, nuns, nurses and teachers,

Please love us all.

And guard us and guide us,

For ever and ever,

Amen.

Id lie in bed wondering who the mysterious Gartis and Gytus were. I believed the prayer was written by my father. When I started going to church I wondered why the priest didnt recite all of the prayer my father had given to him.