First published 2020

Copyright Kevin Shillington 2020

The right of Kevin Shillington to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Published under licence by Brown Dog Books and

The Self-Publishing Partnership, 7 Green Park Station, Bath BA1 1JB

www.selfpublishingpartnership.co.uk

ISBN printed book: 978-1-83952-187-4

ISBN e-book: 978-1-83952-349-6

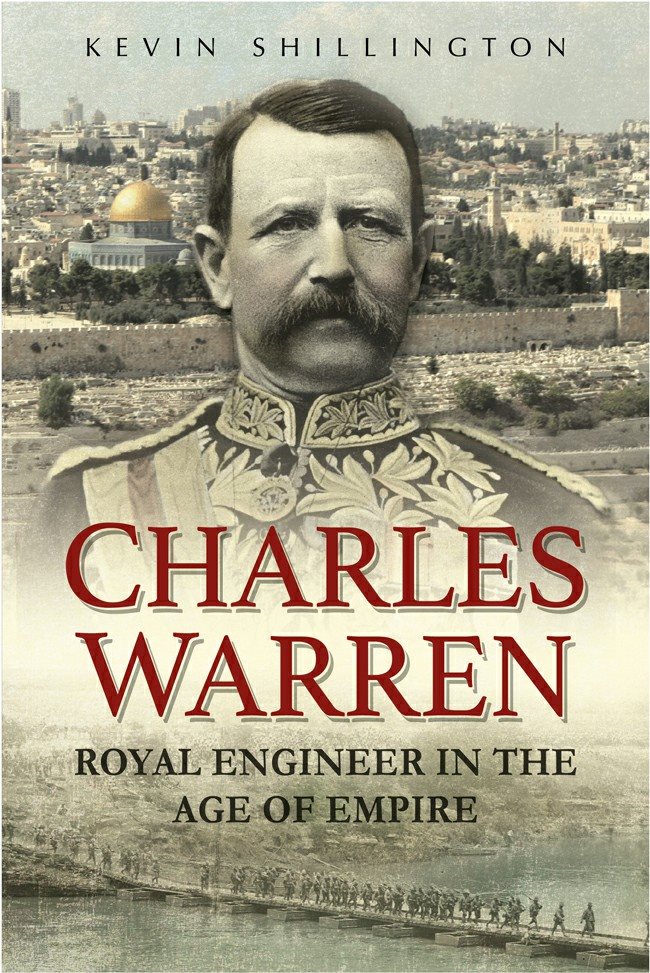

Cover design by Kevin Rylands

Internal design by Tim Jollands

Printed and bound in the UK

This book is printed on FSC certified paper

Contents

List of Maps

Preface

At the time of writing, empire, and statues of imperialists, have been very much in the news. The issue has been given focus in Britain by the countrys widespread failure to recognise the reality of empire, upon which so much of the countrys wealth and claim to world power status was built. That reality was at the expense of colonised peoples, and that is where the concept of benevolent empire falls down.

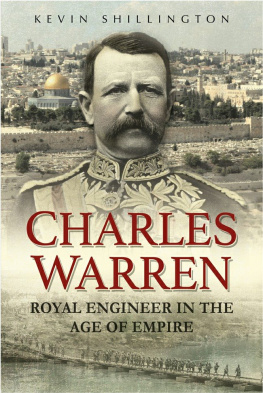

My choice of biographical subject is therefore very apt, for the background to the life of Charles Warren is the British empire during the period of its maximum expansion through the second half of the 19th century. At times, as a Royal Engineer, Charles Warren was a key player in that expansion. The art of surveying and map-making was a central ingredient in the expanding empire of the Victorian era. This placed Royal Engineers, the lite corps of the Victorian Army by virtue of their training, in a powerful and prestigious position in terms of career opportunities, not solely in military affairs. And Charles Warren, a gifted mathematician with a scientific mind, was a Royal Engineer par excellence.

He was born into empire and accepted it as a fact of life. Through his childhood, his father fought as an infantry officer in India and the First Opium War against China. And through his adult career, Charles Warren tried to find a moral imperative within the imperial project. From todays perspective, that may appear a contradiction in terms. But the reality of empire, however one judges it, is never as clear and simple as may appear at first glance, and the ambiguities of empire are well revealed through the life of Charles Warren.

He had a strong sense of duty, instilled in him from an early age by his father, and he accepted whatever task was presented to him. This ranged from pioneering archaeology under the Old City of Jerusalem, to hunting for lost British spies in the desert of the Exodus, even Metropolitan Police Commissioner at the time of the Jack the Ripper murders. But it was in Southern Africa where he most directly faced the contradictions inherent in an expansive British empire. And it was here, over the basic concepts of empire benevolent or rapacious that Warren, a man with a strong religious moral code, first clashed with Cecil Rhodes. Through their clash of moral perceptions, Warren won some victories, but so too, ultimately more powerfully, did Cecil Rhodes.

* * *

There has to date been only one full biography of Charles Warren, written by his grandson Watkin Williams. Published in 1941, fourteen years after Warrens death, it was based largely upon his private papers. The researcher, of course, must treat these sources with a certain level of caution; for they are themselves a selection from the originals and one is left with the intriguing thought of what might have been left out.

To make up for that lack of unpublished private papers, I have researched extensively in libraries and archives and visited all the major places of his long and active life, from Ireland of his early childhood, Sandhurst and the Royal Military Academy of his training, the home of the Royal Engineers in Chatham and his various postings around the world, from Gibraltar where he started his career, to Jerusalem where his name first came to wide public attention, to Southern Africa where on several occasions he played an important role in the nature of the imperial presence there. I have visited Singapore; indeed, the only place that featured prominently in his career that I have not visited is the Sinai desert. At the time of my research it was considered too dangerous on account of current conflict, although no more dangerous, one must admit, than when Warren was there in 1882.

Historians have tended to cast Warren either as the Metropolitan Police Commissioner who failed to catch Jack the Ripper or the General who lost the Battle of Spion Kop, one of the greatest British military disasters of the Anglo-Boer War. He has thus been a much neglected figure. As I have found in researching and writing this biography, it is an important and fascinating story, with many contemporary resonances.

It has been a long haul bringing the book to fruition, and over the years Warren has often had to be placed on the back burner as other, commissioned work has taken over. But it has been a project that I have always been pleased to return to. One of its greatest rewards has been tracking down some of his descendants, swapping stories of family traditions and memories and comparing them with my own discoveries. It is to his descendants and to all those who have helped me over the years that I dedicate this book.

Kevin Shillington

Dorset, England

June 2020

KEVIN SHILLINGTON, an independent historian and biographer, is a graduate of Trinity College Dublin who holds a PhD from SOAS, University of London. His recent books include History of Africa (4th edition 2019) and Patrick van Rensburg: Rebel, Visionary and Radical Educationist (2020).

CHAPTER 1

Background and Early Life

In March 1838 Major Charles Warren (Senior) and his young family boarded ship at Madras. It was the first stage of the long journey home to England for three years well-earned leave. Steam-powered ships were in their infancy, and the Warrens would have travelled under sail, probably calling at numerous ports along the way before heading up the Red Sea for the Gulf of Suez. The weeks of inactivity aboard ship would have provided the 40-year-old major with an unaccustomed amount of time to spend with his wife and young children, as well as to reflect on the past eight years in the service of the East India Company.

He had first arrived in India in October 1830 as a Captain of the 55th Regiment of Foot. He came with his wife of six months, Mary Anne Hughes, who early the following year gave birth to a son. They named their first-born John. It was a name common to every generation of Warrens. Charles had a brother John, Rector of a parish in Cambridgeshire, and their father was Very Revd John Warren, Dean of Bangor Cathedral in North Wales. Over the next six years in India Mary Warren gave birth to three daughters, Margaret, Mary and Charlotte.

Next page