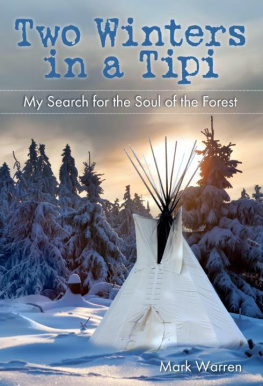

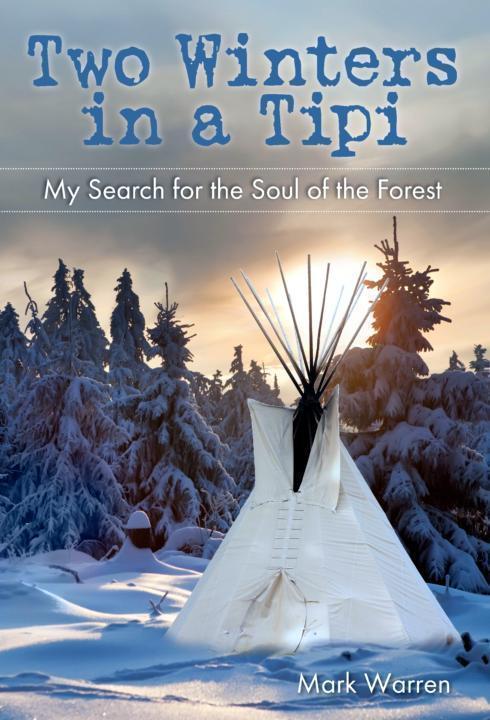

My Search for the Soul of the Forest

Mark Warren

For Elly,

just across the river

ix

ne moonless night during my tipi years, I slipped from my bedding, dressed, and stepped out into the cold. I often did this simply to stand under the stars and listen to the nocturnal sounds coming from the forest bordering the meadow. Clicks, chirrs, and wing flaps marked the pulse of nature's business hours, and I loved nothing more than to audit the flow of nightlife, to feel connected to it if only peripherally.

ne moonless night during my tipi years, I slipped from my bedding, dressed, and stepped out into the cold. I often did this simply to stand under the stars and listen to the nocturnal sounds coming from the forest bordering the meadow. Clicks, chirrs, and wing flaps marked the pulse of nature's business hours, and I loved nothing more than to audit the flow of nightlife, to feel connected to it if only peripherally.

I had practiced this same vigil when I lived in a house, but back then it wasn't a nightly habit. When I did stand on my porch in the wee hours, I was fully aware of how much was going on out there in the shadows, but I knew it then as something separate from my life. Ultimately I would turn my back and return to oblivious sleep in a soft bed surrounded by insulated walls, drawn curtains, and evenly distributed heat. Though a tipi is wonderfully snug, private, and sheltering, a thin line divides outside from inside. Once you step out, you realize that there really has been no transition; you were already a part of the surroundings.

Far down the length of the field, against the lighter shade of starlit grass, eight dark shapes clustered together on a rise. They stood still as boulders. After a few minutes, two of the amorphous shapes drifted apart in slow and silent movements, giving the appearance of black buoys floating on pale, luminescent water. The movement marked them as nocturnal foragers: a herd of deer browsing the succulent new shoots of early spring. It was a scene so pastoral, serene, and otherworldly that it struck me as an invitation; I wanted to be a part of that picture.

For more than an hour, I stalked low in the tall winterkilled grasses as I made my way toward the rise. I moved with patience and fluidity, eventually on hands and knees, and then on my belly. The previous season's dead grasses stood two feet high, wan and brittle, providing cover. The wind was blowing gently toward me, carrying my scent away from the deer. The desiccated grass vibrated with a sustained whisper of tapping leaves and stems, like paper-thin blades trying to sharpen themselves against one another.

Just a few yards from the herd, I slowly raised my head, settled in, and watched them graze. Their profiles were crisply defined. Their heads bobbed down, and when they came up, I could see and hear their jaws grinding laterally as their dark eyes held a steady vigil on the borders of the field. The constant edge of alertness on which they lived was palpable.

Then one of the animals fixed its stare on meand stiffened. Every fiber of its being seemed focused on identifying what I was. There was no stamping of hoof, no snort, no sudden burst of alarm, or dash to escape. The other deer seemed not to notice our silent standoff. Then the vigilant deer stepped away, the others following as if the herd were interconnected by a single delicate thread. Without consciously deciding to do so, I rose to a crouch and flowed with them, deer-like, bent forward at the waist, my torso horizontal.

Still, they didn't bolt. They moved deliberately but without panic, and I was perfectly able to keep up. They were allowing me a moment in the brotherhood of the wilderness. Soon their gliding bodies picked up speed by increments, testing my capabilities, until I was running upright, strong and effortless, fueled by the brisk night air. I was not chasing them but running with them, inside the herd. Quickly veering to either side, I could have touched one's flank. But I didn't. I wanted to do exactly what they were doing. To stretch out my stride with God-given grace. To feel the freedom of flying through the night grass. I had come to be with them-now I was of them.

A boundless energy filled me with preternatural strength, making me feel light and fleet, gathered against gravity as my feet seemed hardly to touch the ground. The wind blew in my face, making a hollow whisper in my ears that masked all other sounds and gave the experience a surreal, dreamlike quality.

We ran like this for sixty yards, together, choreographed by some tacit agreement granted by divine intervention, serendipity, or perhaps the generosity of deer. The night expanded-like that so-called flash of life in the compressed seconds before death. The stars fixed the moment in place with a thousand distant flashbulbs that ensured my detailed memory of the night.

That was nearly thirty years ago. These days, I don't sleep so close to that edge of possibility, nor am I as fleet of foot. More important, insulated walls sequester me, layers of material separate me from the earth, and the vigilance of a thermostat incubates me. As with other men's castles, an abstraction of the moat that encircles it greatly defines mine.

All my life I have paid attention to nature. I followed it as though it were a phantom figure slinking off into the woods, and I had to track it, to know what it was. Such was my nature, which led me through a gamut of adventures, both grand and minute: calling in more than a hundred raucous crows to wheel at treetop level above my hiding place for a half hour as they screamed a chorus of complaint over my newly perfected raven croak; discovering the wildly intoxicating flood of scent exuded from a red-spotted millipede or a crushed black snakeroot seed; walking under the dark mystery of hemlocks while the fold and foam of mountain water manufactured a liquid white light from within; stalking and observing the secret lives of bear and fox, vole and cricket.

I had moved closer to nature with every day of my life. I was, after all, a naturalist, whose life mission was to learn as much as I could about the wild things so that I could teach others. Learning is my passion. Perhaps teaching has served as a justification for the learning. I didn't realize just how much moving into a tipi would accelerate my learning experiences. But catapult me forward it did, like the night I ran with the deer.

ne moonless night during my tipi years, I slipped from my bedding, dressed, and stepped out into the cold. I often did this simply to stand under the stars and listen to the nocturnal sounds coming from the forest bordering the meadow. Clicks, chirrs, and wing flaps marked the pulse of nature's business hours, and I loved nothing more than to audit the flow of nightlife, to feel connected to it if only peripherally.

ne moonless night during my tipi years, I slipped from my bedding, dressed, and stepped out into the cold. I often did this simply to stand under the stars and listen to the nocturnal sounds coming from the forest bordering the meadow. Clicks, chirrs, and wing flaps marked the pulse of nature's business hours, and I loved nothing more than to audit the flow of nightlife, to feel connected to it if only peripherally.