ZONDERVAN

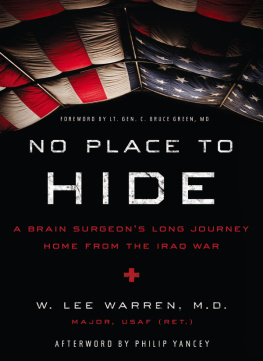

No Place to Hide

Copyright 2014 by W. Lee Warren

ePub Edition March 2014: ISBN 978-0-310-33804-8

Requests for information should be addressed to:

Zondervan, 3900 Sparks Dr., Michigan 49546

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Warren, W. Lee, 1969

No place to hide : a brain surgeons long journey home from the Iraq War / Major W. Lee Warren, MD U.S. Air Force (Ret.).

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-310-33803-1 (hardcover)

1. Warren, W. Lee, 1969 2. Iraq War, 2003-2011Medical care. 3. Iraq War, 2003-2011Personal narratives, American. 4. Joint Base Balad (Balad, Iraq) 5. SurgeonsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

DS79.767.M43W37 2013

956.7044'37092dc23 [B] 2013033127

All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from The Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Any Internet addresses (websites, blogs, etc.) and telephone numbers in this book are offered as a resource. They are not intended in any way to be or imply an endorsement by Zondervan, nor does Zondervan vouch for the content of these sites and numbers for the life of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Cover design: Faceout Studio

Cover photography: Senior Airman Jeffrey Schultze, U.S. Air Force, www.afcent.af.mil

Interior design: David Conn

Printed in the United States of America

14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 /DCI/ 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Lisa

CONTENTS

by Lt. Gen. (Ret.) C. Bruce Green, MD

by Philip Yancey

A fter the fall of Iraq in the spring of 2004, the Air Force Surgeon General determined Wilford Hall Medical Center would lead the 332nd Theater Hospital, Balad ab, Iraq. The base was the hub for logistics and air evacuation out of Iraq, and it was under fire (twenty-plus rocket attacks per week) when our medics arrived. Roughly three hundred medics, a mixture of Air Force, Army, and Australian physicians, nurses, allied professionals, and technicians required to save lives, were sent into harms way to care for wounded warriors and Iraqi citizens injured in the war.

As Wilford Hall Commander, I handpicked the deploying commanders, and every medic knew their friends would follow and inherit their work. It was a harrowing time. We trained for this mission for years, honing skills and modernizing equipment sets, but now friends had to leave families for four to six months to risk life and limb. I will never forget the first two rotations farewells in the auditorium the dedication mixed with fear and excitement in the eyes of the medics, the tears of families, the concern of friends and supervisors seeing the deployers depart.

These medics were incredibly dedicated to saving lives. Their work with the city of San Antonio and surrounding twenty-two counties established a trauma network second to none. Before stepping into Iraq, nurses were added to the team to capture trauma data in a registry for continuous learning. An experienced trauma surgeon, the trauma czar, was chosen to establish the flow for casualties that would optimize survival. In the first weeks these medics eradicated a new drug-resistant bacteria that was contaminating wounds. The survival rate for casualties rose from 90 to 98 percent, and the story began to circulate: Why do Marines carry a twenty-dollar bill in their boot? So that, when wounded, they can tip the helicopter pilot to take them to Balad.

This book captures simply, eloquently, and passionately what it means to be a physician in time of war. Every person who goes to war is changed. My emotional response to these chapters made me pause to consider that our best efforts to support medics were inadequate. It captures the reality so many experienced and the difficulty of returning to everyday life. Over ten years of war, we safely air evacuated more than ninety thousand injured and ill from Iraq and Afghanistan five thousand were the sickest of the sick. This very personal story captures the essence of what it takes to be a military physician and the challenge for our nation to reintegrate all who deploy to war.

Lt. Gen. (ret.) C. Bruce Green, MD

20th AF Surgeon General

T he stories told in this book are all true, as experienced during my time in Iraq in 2004 2005. I obscured details in some of them, as well as the names of some doctors, nurses, and medics, to protect their anonymity. I also changed the names and identification numbers of all Iraqis and terrorists and all American soldiers with the exception of Paul Statzer, who gave me permission to use his name and story.

I changed some names for practical reasons. For example, there were three Todds with me in Iraq. To avoid having to say Todd the neurosurgeon, or Todd the therapist, or Todd the heart surgeon, I simply renamed two of them.

Since there were so many different people on the worship team and so many different chaplains, I combined a lot of the people into two characters John and Chaplain W.

I am sure that some of the events I discuss in the book would sound different if told from the perspective of other doctors at the base or the soldiers or terrorists or Iraqis who were part of my story. In the chaos of battlefield medicine, it was common for us to hear from a soldier that our patient was a terrorist, or that the injuries had been caused by an IED, only to find out later that the patient was actually a good guy or that the IED was actually a land mine. Chalk it up to the fog of war as well as to the differences in the accounts of any two witnesses describing the same event.

The dialog in this book was recreated from memory, and since it has been eight years since I was in Iraq, I am sure that some of the dialog, while true to the spirit of the conversation it recreates, nevertheless expresses it in words that differ from those actually spoken.

Finally, I didnt include all 120 of my emails home in this book. I modified and combined some of them to make sense in the context of this book. They were also edited for grammar (somehow I managed to make a few grammatical errors while emailing from the combat zone), and names were changed where appropriate.

S it on your body armor on the flight in.

Excuse me?

The C 130 pilot laughed. It was December 28, 2004, and we were in the Base Exchange, or BX, at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar. He looked at his colleague and said, The major heres never been in Iraq, sir.

The shorter one wore silver oak leaves on his flight suit a lieutenant colonel. And like the pilot whod just given me the advice, he also wore pilots wings. He leaned closer and said, He said you should sit on your Kevlar. As opposed to wearing it. The bullets come in from below.

They walked away chuckling, no doubt at the bewilderment on my face.

I checked my watch: 1600 hours. Four p.m. Eight hours to go.

I shrugged their advice off uneasily and continued checking off the last few items from the list of things that Id been told since arriving here two days before from San Antonio I would need at my new deployment. Things that had not been on the official packing list but that others had found useful, such as earplugs for the plane ride I was waiting for.

The one that would deliver me to the war.

Next page