The First Ladies Fact Book

The Childhoods, Courtships, Marriages, Campaigns, Accomplishments, and Legacies of Every First Lady from Martha Washington to Michelle Obama

Bill Harris

Revised by Laura Ross

Copyright 2005, 2009, 2011 by Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Published by:

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc.

151 West 19th Street

New York, NY 10011

www.blackdogandleventhal.com

Distributed by:

Workman Publishing Company

225 Varick Street

New York, NY 10014

Cover design by Liz Driesbach

Contributing Writers:

Jim Callan

Michael Lewis

Stephen Spignesi

Richard Steins

Laura Ross

Thomas J. Craughwell

Photo Research:

Sarah Parvis

ISBN: 978-1-57912-891-3

eISBN: 978-1-60376-313-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc.

Contents

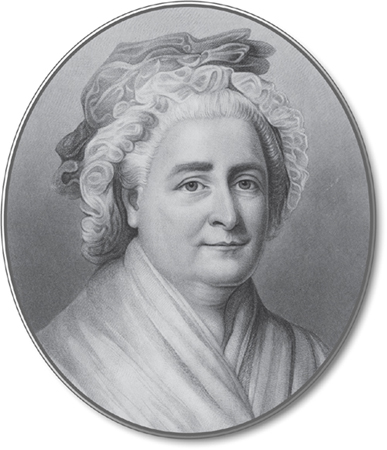

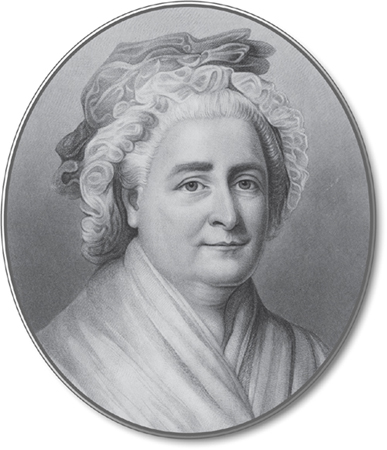

Martha Washington

Martha Dandridge Custis Washington

Born

June 2, 1731, Chestnut Grove, New Kent County, Virginia

Parents

John Dandridge and Frances Jones Dandridge

Marriage

1750 to Daniel Parke Custis

Children

Daniel Custis (1751-56); Frances Custis (1753-57); John (Jacky) Custis (1755-81); Martha (Patsy) Custis (1757-73)

Widowed

1757

Remarried

1759 to Colonel George Washington (1732-99)

Died

May 22, 1802, Mount Vernon, Virginia

Lady Washington

When sixty-year-old Martha Washington arrived in New York in the spring of 1789 to join her husband, the newly inaugurated president of the United States, she had no notion of what to expect, nor of what was expected of her as the First Lady of the United States.

George Washington himself was facing a similar challenge. The Constitution outlined most of his state duties, but it was quite silent on the ceremonial roles he would have to play. He had recently given eight years of his life to freeing the American people from a monarchy, and they regarded him as one of their own; but, in fact, President Washington was a wealthy Southern planter and by nature a patrician in a society that had, in theory, done away with such social distinctions. With no role model before him, George had to figure out what it meant to be presidential, and how to conduct himself as the leader of this fledgling nation of free people. The new office itself was different from any other the world had ever seen. The American president is the head of state with all of the ceremonial obligations that go with it, and he is also the head of the government, directly responsible to the needs of the people he serves. George was also very sensitive to the fact that the ways he handled the office would establish a precedent for all of the American presidents who would follow him.

The members of his official family had debated for weeks over how the citizenry should address him and, by custom, his successors. Vice President John Adams was firmly on the side of the Senate, which had voted that the proper way ought to be His Highness, the President of the United States and Protector of Liberties. The House of Representatives, however, in a less formal and more democratic frame of mind, insisted that it should simply be Mr. President. Although Mr. Adams said the latter fell on his ear as the officer of some local insignificant organization, the egalitarian Mr. President won out in the end.

The debate extended to how the First Lady should be addressed as well, and although it, too, came down to a simple Mrs., Martha had come to New York enthusiastically hailed as Lady Washington, an honorific given to her by the soldiers under her husbands commandfor it was plain for anyone to see that Martha was every inch a lady. One of the French officers who served in the Revolution once said that she reminded him of a Roman matron, and nothing suited her bearing more aptly.

It was what was expected of the daughter of one of the first families of Virginia. Born Martha Dandridge, the daughter of a wealthy tobacco planter, John, she grew up in a world of private tutors, attentive servants, and spirited horses. And after she was introduced into society at age fifteen, her life was filled with a constant round of balls, parties, and formal dinners. When Martha was seventeen, she married Daniel Parke Custis, a man even wealthier than her father, and she became the mistress of the Custis plantation, called the White House, not far north of the Virginia capital at Williamsburg, which was the epicenter of the colonys social life.

Marthas status grew, especially among eligible bachelors, when Daniel died eight years later, leaving an estate that made her the wealthiest widow in Virginia, not to mention the most attractive, at the age of twenty-five.

She chose to shun their advances, concentrating instead on running the Custis plantation and raising the surviving two of her four children: four-year-old John, who was called Jacky; and a girl of two named for her mother but, like her, affectionately known as Patsy. But then a new man caught her eye. His name was George Washington.

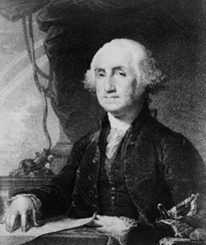

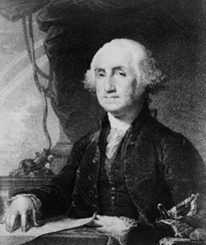

Painter Gilbert Stuart created many images of George Washington. This one appears on the dollar bill in a reversed engraving.

Colonel Washington had made a name for himself as a hero of the frontier war against the French and Indians, and Martha had met him several times when he appeared at Williamsburg for consultations with the governor. She had been impressed by his appearance, tall and lithe with cool blue eyes, and she was quite taken by his quiet dignity, formality, remoteness, and even his shyness around women, all qualities that were glaringly in short supply among the swains who were pursuing her. But it was all just a passing fancyshe was certain of that.

Martha Washington married her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis, in 1750 and moved into his mansion, which he called the White House!

Martha met him again at a dinner party in the early spring of 1758, and they lingered in the parlor together after the other guests had left. It was an evening of polite conversation between two plantation owners, and only George had any inkling that it was anything more than that. His intentions finally dawned on Martha when her children were brought in to say goodnight and the soldier enchanted them as well.

Martha and George met again soon afterward when he invited himself to her home on his way back from another trip to Williamsburg. She had talked herself out of any idea of romance by then, but he brought it back to the top of her mind by the way he treated her servants and, more important, in the easy bond he established with her children. There would be two more visits before he asked Martha to marry him, and by then she was joyfully ready to accept his proposal. But first, he went off to take care of some urgent unfinished business with the French, which he promised her would be his last military campaign.