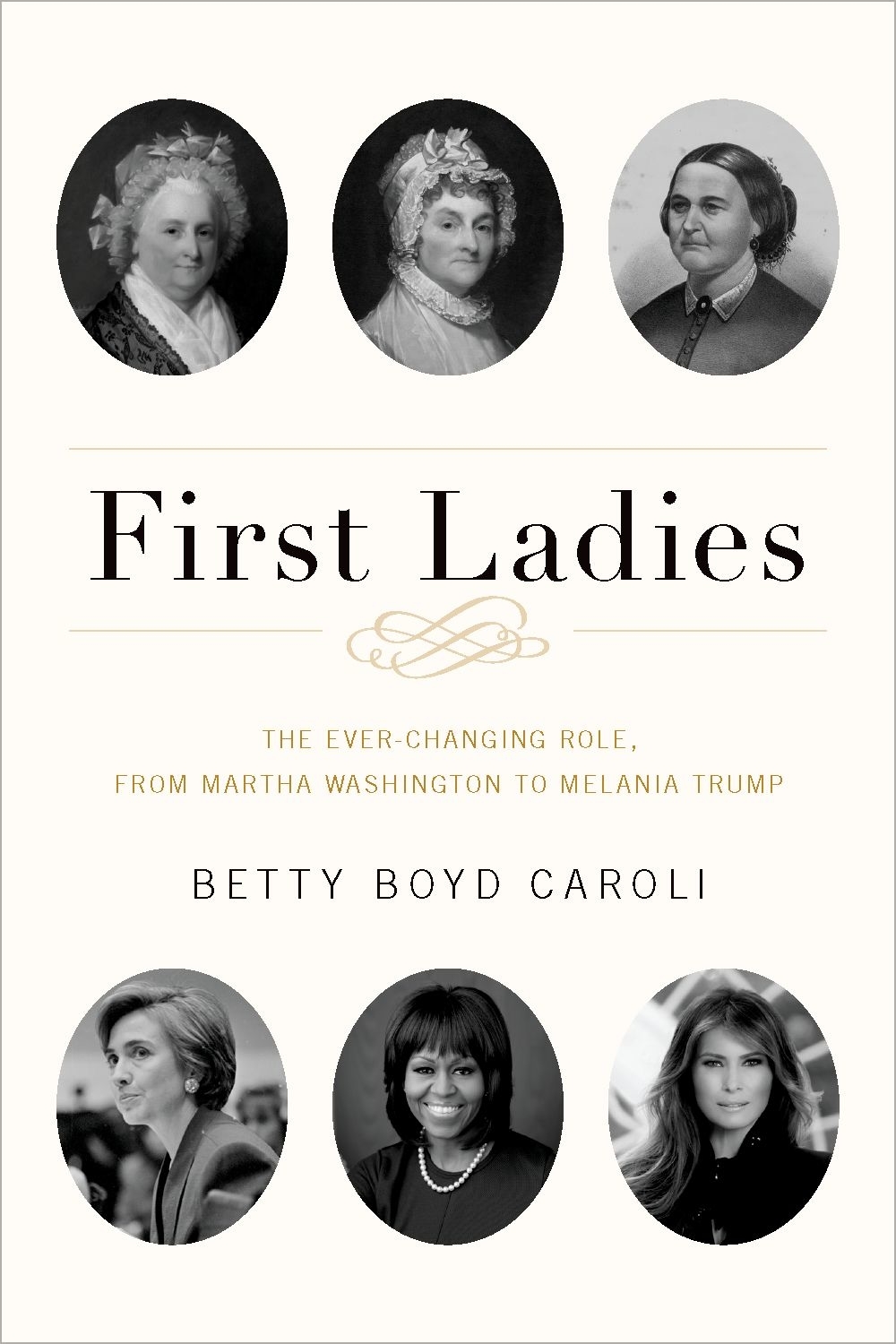

I NEVER WANTED TO WRITE about women who became famous simply because of the men they married, and when an editor suggested I explore First Ladies, I interpreted what she was inviting me to do as presidential history. That was nearly forty years ago, and what I expected to be a one-time treatment of White House occupants turned into multiple editions, encompassing not only presidents but womens history, national politics, and the press.

The first Oxford University Press edition of First Ladies appeared in 1987, and the book grew as I added the records of four more First Ladies for subsequent OUP editions in 1995, 2003, and 2010. The last of these did not include two important chapters from the earlier editions: First Ladies and the Press and The Women They Married. Readers delving into those topics should consult the earlier editions.

Book club editions of First Ladies came out in1989, 1993, 1997, 2001, and 2009. In spite of having the same title as the OUP editions, the book club versions are very different, without source notes and lacking material on womens history and the press that I included in the OUP books.

Along with the different editions of First Ladies I produced two illustrated histories that enriched my appreciation of the subject: Americas First Ladies and Inside the White House. Researching and writing about one presidential family (The Roosevelt Women, 1998) and one presidents marriage (Lady Bird and Lyndon: The Hidden Story of a Marriage That Made a President, 2015) also altered my thinking.

I have profited from the insights and assistance of more individuals and institutions than I can possibly acknowledge here. Each edition of First Ladies carries its own list, and here, for the final edition, I am singling out persons and groups that have been particularly helpful these last few years. Topping the list is my literary agent, Susan Rabiner, whose sage advice and stalwart support have continued unabated since we first worked together on Todays Immigrants, Their Stories. Over the years, the team at Oxford University Press has changed but not their professionalism and collegial support. Tim Bent, currently Executive Editor, and his assistants have enthusiastically backed my work through this fifth edition.

New York City offers authors many congenial settings for exchanging ideas and networking. I have profited from several but want to thank particularly the members of the seminar, Women Writing Womens Lives, and two smaller groups: the Narrative Writing Group and the Gotham Book Group.

Livio Caroli initially found the label First Lady a curious designation, so unlike anything heard in his native Italy. But over time, he has become an ardent backer of my research, and, coincidentally, Italy has imported First Lady into its lexicon. He richly deserves the dedication.

New York City, October 1, 2018

LIKE MANY HISTORIANS of womens records, I was not initially attracted to the prospect of writing a book on presidents wives. (Hillary Rodham Clinton had not yet made the kind of headlines that encouraged serious discussion of the job of First Lady.) What value could there be in studying a group of women united only by the fact that their husbands had held the same job? The 1970s and 1980s had finally focused attention on women who achieved on their ownwho, then, would want to read about women who owed their space in history books to the men they married? If presidents wives had remained footnotes to history, perhaps that was what they deserved.

My curiosity was piqued when I looked at what had been published on the subject. Even a cursory reading of the standard reference work on women revealed a striking pattern among presidents wives. Most of them came from social and economic backgrounds significantly superior to those of the men they married. Many of the women wed in spite of strenuous parental objection to their choices, and some of the men were younger than their brides. Recurring phrases hinted that the women assumed more control over their lives than I had imagined, and I began to wonder if I had mistakenly assigned them a free and easy ride alongside their prominent husbands. Several of the wives had eased the financial burdens of their households by managing family farms, teaching school, and working as secretaries after their marriages. Other information pointed to a pattern of early exposure to politics, and I was struck by the number of uncles, fathers, and grandfathers who had at one time held political office. Perhaps the women deserved a closer look.

As soon as I examined the womens unpublished letters, I was intrigued. Who could read Lucretia Garfields poignant puzzlings in the 1850s about what being a wife meant and not then go on to learn how her marriage turned out? What about the indomitable Sarah Polk whose blunt letters and letters of others singled out as particularly opinionated and astute? Who would not want to read what the magazines of the 1840s said about her? Was the handwritten memorandum on the subject of Mary Lincolns insanity trial to be believed? What about the mysterious Eliza Johnson who was much maligned as a hill woman of little education? Why did her son, then enrolled at Georgetown, write her a beautifully penned, grammatically perfect letter and ask her to excuse the mistakes? These and dozens of other questions arose.