Contents

Page List

Guide

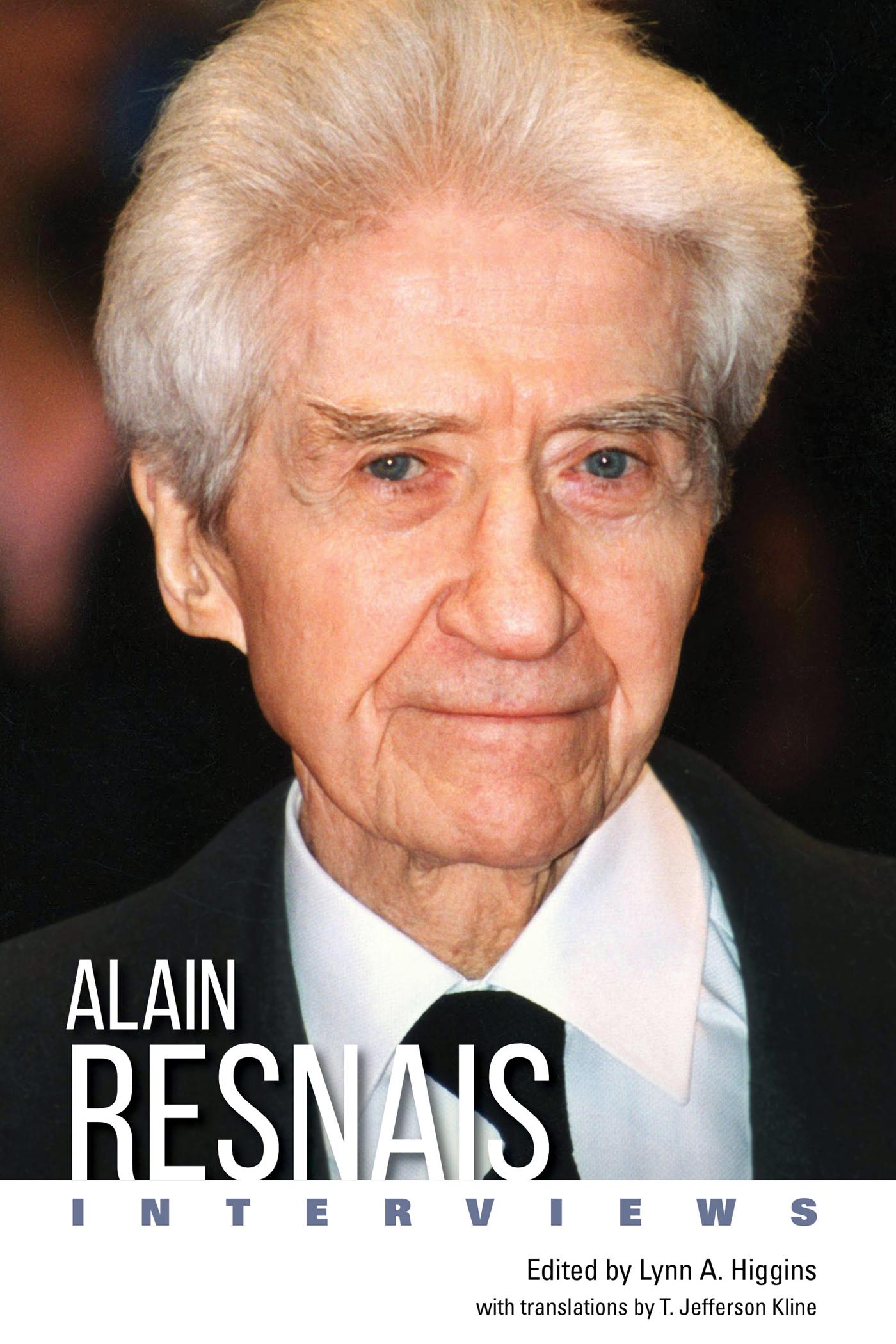

Alain Resnais: Interviews

Conversations with Filmmakers Series

Gerald Peary, General Editor

ALAIN

RESNAIS

INTERVIEWS

Edited by Lynn A. Higgins

with translations by T. Jefferson Kline

University Press of Mississippi / Jackson

The University Press of Mississippi is the scholarly publishing agency of the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning: Alcorn State University, Delta State University, Jackson State University, Mississippi State University, Mississippi University for Women, Mississippi Valley State University, University of Mississippi, and University of Southern Mississippi.

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a generous donation from Dartmouth College.

Copyright 2021 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2021

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021938282

Hardback ISBN 978-1-4968-3394-5

Trade paperback ISBN 978-1-4968-3393-8

Epub single ISBN 978-1-4968-3395-2

Epub institutional ISBN 978-1-4968-3396-9

PDF single ISBN 978-1-4968-3397-6

PDF institutional ISBN 978-1-4968-3398-3

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Contents

Jean Michel Carta and Michel Mesnil / 1960

Andr Labarthe and Jacques Rivette / 1962

Robert Benayoun, Michel Ciment, and Jean-Louis Pays / 1966

O. Revault dAllonnes / 1967

Jacques Belmans / 1968

Richard Roud / 1969

James Monaco / 1975

Richard Seaver / 1975

Robert Benayoun / 1980

Tom Milne / 1980

Alain Masson and Franois Thomas / 1984

Frederic Tuten / 1984

Jean-Daniel Roob / 1986

Franois Thomas / 1986

Birgit Kmper and Thomas Tode / 1995

Franois Thomas / 1999

Pascal Mrigeau / 2003

Franois Thomas / 2006

Gary Crowdus and Richard Porton / 2010

Franois Thomas / 2012

Franois Thomas / 2014

Index

Introduction

Now considered one of the most innovative and influential filmmakers of the twentieth century, Alain Resnais (19222014) did not set out to become a director. In the interviews here, he more readily considers himself a craftsman than an artist, citing the practical choices that shaped his career. (His early films were commissions, for example.) What can we make of a filmography that includes a pathbreaking short documentary about the Nazi extermination camps (Nuit et brouillard / Night and Fog, 1955) and a feature juxtaposing the German Occupation of France with the bombing of Hiroshima (Hiroshima mon amour, 1958) on the one hand, but also a short documentary advertising a plastics factory (Le Chant du styrne, 1958) and a formalist jewel (LAnne dernire Marienbad/Last Year at Marienbad, 1960) that seems disconnected from any reality at all external to itself? And those are just the early years! Resnais went on to experiment with musical comedies, operettas, adaptations from theater and one from a novel, animation, and more. His range of genres should nevertheless not surprise us, given the far-flung passions that inspire his work, from Breton mythology to comic books and from Surrealism to neuroscience. Yet, viewed retrospectively, Resnaiss corpus of work has remarkable continuity, and his career was foreshadowed as far back as his early childhood. Both the variety of his choices and the overall coherence of his artistic vision are readable in the interviews collected here.

Born in 1922, Resnais was the only child of a pharmacist in Vannes, a small city in Brittany full of medieval buildings, in a region known for its mysterious Stone Age formations and ancient Celtic legends. The provincial town was also stolidly bourgeois, and children were expected to conform to rigorous norms of behavior and belief. Raised as a strict Catholic, the young Resnais was allowed to visit only the parish movie house, not the secular one next door. His horizons further limited by asthma, he was home schooled as a child and inclined toward quiet entertainments, such as reading comic strips and adventure stories. And from the beginning, there were movies. At the age of eight, he invited friends to enjoy silent Laurel and Hardy comedies projected on a wall and accompanied by recorded music. Anticipating his future vocation as a film editor, he cobbled together leftover snippets of advertising footage to illustrate stories of his own invention. For his thirteenth birthday, his parents gave him a Kodak 8mm camera, with which he filmed his friends starring in adventures drawn from popular novels about the fictional criminal Fantmas.

At fourteen, Resnais was sent to school in Paris. Finally, he could see whatever movies he liked, without parental or church supervision. Throughout his life, he retained vivid memories of films viewed during the 1930s and 1940s. He loved the Surrealist silent short Un Chien Andalou (1929), by Luis Buuel and Salvador Dali. The 1933 American musical 42nd Street, with its kaleidoscopic dance numbers choreographed by Busby Berkeley, stirred his ambition to make a musical. He was impressed by the social and psychological subtleties of Jean Renoirs La Rgle du jeu (The Rules of the Game, 1939), and he appreciated the musicality and spare allegorical sensibility of Robert Bresson. He discovered Luchino Visconti, King Vidor, and Michael Curtiz, and of course, he loved the silent Fantmas adaptations by Louis Feuillade.

Shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, Resnais headed south to prepare his baccalaureate exams. He never did complete his bac, but in Nice, he became friends with Frdric de Towarnicki, who would later be known as a journalist, translator, and author. Sharing a passion for comic strips, especially the fictional detective Harry Dickson (whose adventures Resnais had collected since childhood), the two youths focused their energies on adapting this American Sherlock Holmes to the screen. They would pursue this venture for more than two decades before abandoning it. In the meantime, the project brought Resnais into contact with a network of interested supporters that included writer-musician Boris Vian, producers Pierre Braunberger and Anatole Dauman, and eventually the author of the Dickson stories, Jean Ray. Back in Paris during the German Occupation, the two young men remained friends, and when Towarnicki, a Polish Jew, was forced into hiding, Resnais crisscrossed Paris on a bicycle to take him meals.

Also during the Occupation, Resnais decided to study acting and enrolled in the Cours Simon, a Parisian school for the performing arts. He soon concluded he lacked the temperament to become an actor, however, and so in 1943, he applied and was accepted into the newly created national school for advanced study in cinematic arts (the IDHEC). What he chose to study was editing (le montage). Over the next few years, he would edit his own short films and others made by friends, including Franois Truffauts first short film, Une Visite, and Agns Vardas first feature, La Pointe Courte (both 1954). Originally a photographer in the theater, Varda gave the young Resnais a Leica camera, with which he shot studio portraits for actors. Later, he would publish a volume of photos with commentary by Spanish expatriate author and anti-Franco activist Jorge Semprun. Resnais and Varda remained friends, and he would call on Semprun to collaborate on scripts for several of his own films.