Do

Fhreadaidh Dhmhnaill Bhin

Fred Macaulay

(1925-2003)

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sybil Macaulay for the great help she gave me in reading and criticising the whole manuscript of this book; without her encouragement it might never have seen the light.

I also want to thank Ray Burnett for first arousing my interest in Columba, Christian Aikman for telling me about the Sharpening Stone, Ronnie Campbell for showing me where it was and my publisher Neil Wilson for all his help and his soothing advice about maps. Finally I must not forget my two dear black Labradors, Clova and Phemie, who walked about in the Great Glen with me and spent so much time squeezed under my desk while I worked.

Authors Note

The reader may feel a little confused by the many Gaelic names of people and places they will encounter in these pages, some of which appear in pure Gaelic. some in an English equivalent and some halfway between the two. I have tried to give these names the forms in which they are most often found in the literature and hope that the result is not too aggravating.

CONTENTS

I

The Great Glen

This great opening is called by the generall name of Glenmore [Gleann Mr]. The extremitys of these mountains gradwally declyning from their several summitts, open into glens or outlets, where yow have various views of woods, rivers, plains, and laiks, and the torrents, or falls of water, which every here and there tumble down the presipices, and, in many places, seem to breck through the cliffs and cracks of the rocks, strick the eye more agreeably than the most curious artificiall cascades.

In a word, the number, extent, and variety of the several prospects; the verdure of the trees, shrubs, and greens; the odd wildness of the hills, rocks, and precipeces; with the noise of the rivoletts and torrents, brecking and foaming among the stones, in such a diversity of collowrs and figures; the shineing smoothness of the seas and laiks, the rapidity and rumling of the rivers falling from shelve to shelve, and forceing their streams through a multitude of obstructions, have something so charmingly wild and romantick as even exceeds discription.

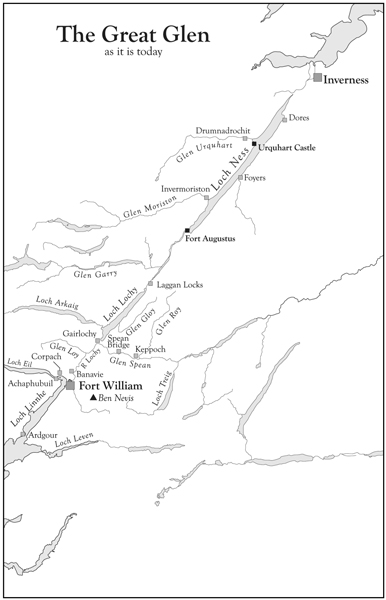

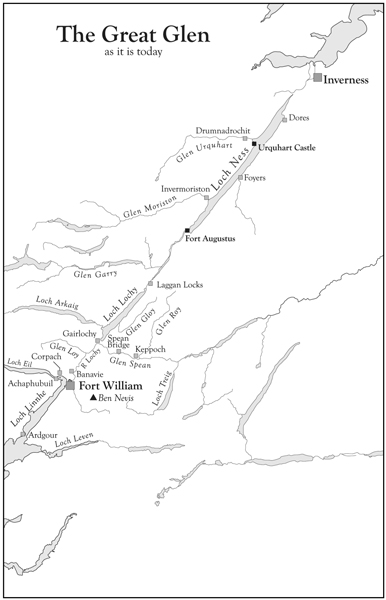

John Drummond of Balhaldy

IF THE TSAR of all the Russias had drawn a line on the map with a ruler from Inverness to Fort William to show where a new railway was to run, as we are told Tsars were wont to do, it could hardly have been straighter than Gleann Mr (the Great Glen). It is a glen formed not by the action of water seeking its way forward along the easiest path, but by the movement of the earths crust ruthlessly splitting rocks asunder along a fault line. It was formed nearly 400 million years ago by a colossal upheaval during which the most northerly part of the land mass was sheared and pulled away roughly 65 miles towards the south-west. The wide and relatively flat bottom of the glen was then carved out by glaciers during the Ice Age, but rock movement is not yet complete and many earthquakes are still recorded, most of them, fortunately, only very small ones.

After the Ice Age the glaciers melted their progress is charted by the parallel roads of Glen Roy leaving what eventually became a series of lochs with the rivers that drain and feed them, the whole creating an almost continuous watery boundary between this furthest section of what is now Scotland the last slice we might term it and the rest of Great Britain. It is rather as though a giant had placed his right hand on the major land mass and torn the top portion away with his left hand and had then, instead of discarding it, put it back, but out of alignment. It is still grinding its way south-westwards.

As the Ice Age receded the earth warmed up and plant life began to appear. The monocultures of spruce with their tightly packed trees and dark, barren forest floors, which cover many of the hills today, were mercifully absent until the last century, but the magnificent Scots pines, which can reach 50 to 70 feet in height, early began to clothe the slopes of the glen, followed by the Druids sacred tree, the oak, and by other species such as birch, willow and alder. Smaller bushes bog myrtle and juniper pushed up and fragile flowers began to spread over the floor of the glen. Then came the animals reindeer, lynx and brown bear, probably all gone by the tenth century. Wild boar and beaver persisted for longer. Deer too were there but perhaps in smaller numbers than today because of the presence of wolves which did not die out until the 18th century, the last having been killed, it is said, in 1743.

The modern motorist might well be forgiven for thinking the glen far from straight as he weaves his way round interminable twists and bends to avoid outcrops of rock or invasive loch or river, but there are places where he is bound to acknowledge its straightness; at the foot of Loch Ness, for instance, where that great water stretches away to the north, further than the eye can see; or at the slope by Aberchalder where the four miles of Loch Oich and the dry land which separates it from Loch Lochy and, on a clear day, Loch Lochy itself are laid out before him, while from somewhere south of Corriegour beside Loch Lochy there is another straight vista down to the hills opposite Fort William and to the Ardgour hills fringing the Firth of Lorne.

The water levels in the lochs and rivers have altered down the centuries and we can only guess what they were at any particular time. These levels have been influenced recently by the dams built to supply electricity, but before then they were subject only to natural processes, to rainfall and rock movements and the unceasing force of the wind.

The glen is bounded on either side by great hills, in the south including Ben Nevis, the greatest of them all. In winter there are wide snowfields on the slopes of these hills and even in midsummer patches of snow remain on the northern faces. A fall of snow shows up every undulation, every rock, every hollow which the softer days of spring and summer hide in clouds of heather and deer grass.

In fierce winds the lochs turn grey and fringe their tossed waves with spumes of white. On still, damp days they pull down thick mists and hide beneath them, drawing the shining birches and the dark heather into their fitful whiteness to wait, unseen or partly seen, until the sun breaks through. Sometimes the lochs are still and, like giant looking-glasses, hold the trees and the hills in a spell beneath their waters.

Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemaeus), the astronomer and geographer who lived from 90-168AD recognised the Caledones, who lived along the Great Glen, as the dominant tribe in the north of Scotland, whereas the Romans gave the name of Caledonia to the whole area which, from their point of view, was inhabited by totally barbarous tribes. These barbarous tribes came to be known as Picts Latin picti (painted people) perhaps from their delight in painting their bodies, which they may well have done to frighten their enemies and not merely as a decoration, though whether they were as highly decorated as some illustrations suggest we may never know.

One might think that the Great Glen must have been welcome as a highway for travellers from the broken rock-strewn coastline of the south-west to the cold waters of the North Sea, from the fertile plains of Moray to Moluags blessed isle of Lismore, yet a look at the many maps plotting the presence of, for instance, Pictish monuments and archeological sites, thanes, nunneries and monasteries, would suggest that not very much was going on there in the early Christian period although plenty of Bronze Age remains have been uncovered. There was little good agricultural land and most of the glen was, of course, a long way from the sea, which was the favoured medium for the transport of people and goods until the last two hundred years or so. As journeys through this glen must have involved fighting ones way over hills and rocks and negotiating lochs, rivers, waterfalls and bogs there may have been little settlement along this apparently favourable route in earlier centuries.