This edition first published in hardcover in the United States in 2012 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact

Copyright 2012 by Robert Zorn

Foreword copyright 2012 by John Douglas and Mark Olshaker

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-46830-193-9

To the memory of my father, Eugene C. Zorn, Jr.

When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever

remains, however improbable, must be the truth.

S IR A RTHUR C ONAN D OYLE

C riminal investigation is a collaborative process, and behavioral profiling is one aspect of that investigation. We stressthat regardless of the Hollywood image attached to profilers in recent years, they are not the ones who catch the criminals.

What a good profiler can doand we note that, like every other profession, they come in all degrees of competenceis eitherto refocus or redirect an investigation. We do this by studying the crime scene photographs, detective and evidence reports,medical examiner protocols, interviews with victims or their survivors and friends, and any other relevant data that can besupplied. What we try to come back with is a description of the unknown subject, or UNSUB in police jargon, including sex(generally male); age; race; marital, educational and socioeconomic status; whether he is a local or from somewhere else,and if local, where he might live; likely triggers or inciting factors for the crime; the types of behaviors we would expectto see post-offense; and strategies that might help lead to his identification and arrest.

Depending on the nature of the crime and how it was perpetrated, one or another of these factors may be emphasized. But whatwe cant offer, despite the joking request were often handed by local law enforcement agencies, is his name, address andphone number. Well describe the offender, we tell them, but it is up to you to identify him from your own suspect list, orgo out and find new suspects based on what we tell you.

Some years ago, when we set out to write our book The Cases That Haunt Us, we wanted to take a fresh and objective look at murder cases that for one reason or another had captured the public imaginationand that, for one reason or another, either remained unsolved or the subjects of ongoing and passionate controversy. We intended to do this by applying everything we had learned about behavioral profilingand modern criminal investigative analysis as practiced by the FBIs National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime atthe Bureaus academy in Quantico, Virginia. We took on cases from the 1888 Whitechapel Murders of Jack the Ripper in VictorianLondon up through the 1996 killing of six-year-old JonBenet Ramsey in modern-day Boulder, Colorado.

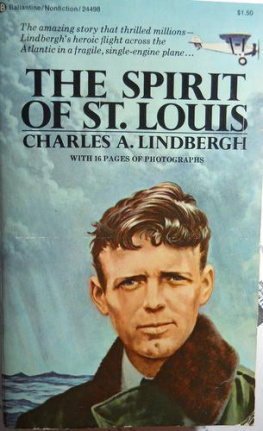

One of the most intriguing, perplexing, and poignantly tragic cases we analyzed was the 1932 kidnapping and murder of littleCharlie Lindbergh, the twenty-month-old firstborn of the Lone Eagle and his wife Anne Morrow, the most famous couple in theworld. It was not for nothing it was dubbed the Crime of the Century.

Pressure to solve the case was intense. Police investigators initially focused on their belief in a small group of co-conspirators.But after a trace of one of the ten-dollar ransom bills led to Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a German immigrant carpenter livingin the Bronx, evidence seemed to begin falling into place. So once they had their man and were able to put him on trial, mosttalk of a conspiracy silenced. And since Hauptmanns 1936 execution in the New Jersey electric chair without ever having admittedinvolvement, the focus of the controversy has been primarily on the question of whether he did it or was framed by a law enforcementestablishment more concerned with closing a notorious case than seeing justice done.

In our own investigation and analysis, we ended up on a somewhat middle, but no less controversial, ground. Going back tosome of the original police suppositions, we concluded that Hauptmann was unquestionably involved with the crime but couldnot possibly have acted alone. We profiled as accomplices at least two other members of the German immigrant community, contemporariesof Hauptmann, living in the South Bronx, one of whom would have been the ringleader or idea man, and the other a compliantfollower.

That was where the matter stood until the summer of 2011, when a man named Robert Zorn contacted us to say he had read The Cases That Haunt Us, believed we were correct in our conclusions and, whats more, thought he had the names and identities to fill in our profileof the Lindbergh kidnappers.

This kind of thing actually happens more often than one might think. Over the years we have been presented with alternativetheories to Jack the Ripper, the Green River killer, the Unabomber, the BTK strangler, the Black Dahlia slayer, and the Zodiac,among others, and none of them has ever panned out. But Mr. Zorns story about his father Gene and his own years-long transatlanticinvestigation after his dads passing sounded at least plausible, so we invited him to come present his findings and evidenceto us in person.

Over the course of six or seven hours Bob walked us through the background, the physical indicators, photographs, handwritingsamples, temporal and geographical links, firsthand accounts of people who had known the subjects and opinions from variousexperts he had consulted. In sum, he connected more dots than we had ever seen connected in this most baffling of all contemporarymurders.

Bobs quest began with his father Genes reconstructed belief that as a teenager living in the South Bronx he had known menwho might have been involved with the crime, so he set off to determine whether his dads analysis held up to close scrutiny.While we had done the profiling, Bob did the work a modern police detective squad would do in qualifying a suspect. He wasmeticulous, thorough, and always healthily skeptical.

When he finished his presentation, we said that while we could not be one hundred percent certain of his conclusion withoutdirect comparisons of fingerprints, handwriting exemplars and/or DNA sequencing, should any of these be available, we werecertain of our own profile and his subjects were the best fit that anyone had ever come up with. They made logical sense,and if this had been an actual police investigation, this is where we would advise them to concentrate their investigativeefforts.

So now we leave it to each reader to confront and evaluate Robert Zorns evidence and argument for him or herself. We thinkyou will be as intrigued as we were in this important addition to the literature of criminal justice and the annals of theCrime of the Century.

J OHN D OUGLAS AND M ARK O LSHAKER

My father remembered the case well. It had happened in 1932, when he was a boy in the South Bronx. As he turned the pages, he started to remember more.

The author contended that Bruno Richard Hauptmann, the man who went to the electric chair for the crime, did not accomplishit alone. Because of Hauptmanns grim silence to the very end, however, his accomplices, including a man with a German accentwho called himself John, were never found. The article mentioned the Bronx and one of its landmarks, Woodlawn Cemetery, aswell as nearby Englewood, New Jersey, where Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh had lived early in their marriage.

Next page