Berg, A. Scott. Lindbergh. New York: G.P. Putnams Sons, 1998.

Falzini, Mark W. Their Fifteen Minutes: Biographical Sketches of the Lindbergh Case. New York: iUniverse, Inc., 2008.

Fisher, Jim. The Lindbergh Case. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987.

Gardner, Lloyd C. The Case That Never Dies. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004.

Herrmann, Dorothy. Anne Morrow Lindbergh: A Gift For Life. New York: Penguin Books, 1993.

Hertog, Susan. Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life. New York: Anchor, 1999.

Kennedy, Ludovic. The Airman and the Carpenter. New York: Viking, 1985.

Mitchell, Charles H. Did Hauptmann Die in the Chair? Daring Detective 4, no. 21 (June 1936).

Waller, George. Kidnap: The Story of the Lindbergh Case. New York: The Dial Press, 1961.

Whipple, Sidney B. The Lindbergh Crime. New York: Blue Ribbon Books, 1935.

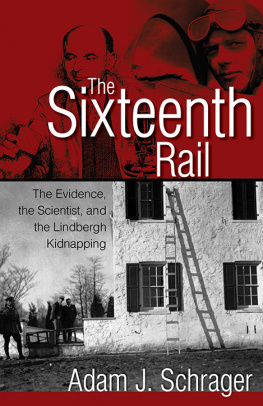

One

THE HERO

At 10:00 p.m. on May 21, 1927, the life of Charles A. Lindbergh changed forever. He had just landed at Le Bourget airfield after a 33 1/2hour flight from New York to Paris, becoming the first person to fly an airplane nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. On the ground, he was confronted with 100,000 crazed and enthusiastic Frenchmen. The next day, the president of France presented him with the Legion of Honor. Medals from the kings of Belgium and England followed.

Upon Lindberghs return to Washington, Pres. Calvin Coolidge presented him with the Distinguished Flying Cross and promoted him to the rank of colonel in the Army Reserves. New York City greeted him with the largest ticker tape parade in the citys history, attended by four million people. Here, he received the Medal of Valor. Lindbergh, the overwhelmed, shy, 25-year-old farm boy from the Midwest, had instantly become the first multimedia herothe worlds first superstar.

The flight marked the beginning of a new life for Lindbergh, one where the public and the press would constantly hound him. This was also the beginning of Lindbergh mania. Two weeks after his flight, the US Postal Department issued a 10 airmail stamp with his plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, depicted on it. There were Lindbergh-themed banks, songs, bookends, calendars, jewelry, tapestries, bed linens, cigars, dinnerware, pins, and good-luck pieces. The world went crazy for anything Lindbergh related!

Lindbergh soon made a nationwide tour to promote aviation. This took him to 92 cities in 48 states, where he delivered 147 speeches and rode 1,290 miles in parades. In December 1927, he embarked on a 9,000-mile aviation tour of Latin America countries. While spending Christmas in Mexico with the American ambassador, Dwight Morrow, he met his future wife, Anne Morrow.

When Lindbergh returned to the United States, President Coolidge presented him with the Congressional Medal of Honor, and his plane was retired to the Smithsonian Institution. Lindbergh was exhausted and longed for peace and quiet. After he married, he needed to find someplace to live, far away from the public and press.

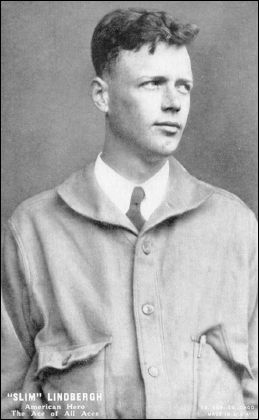

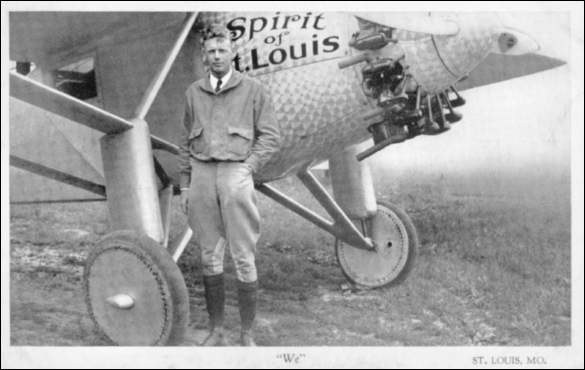

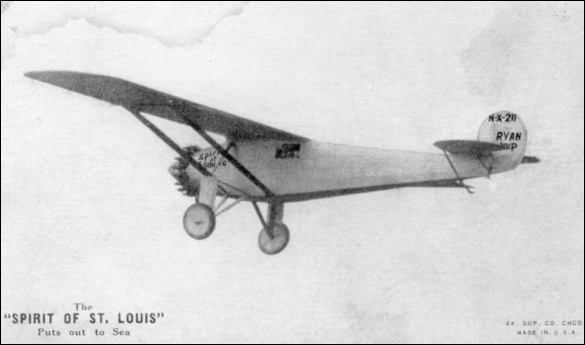

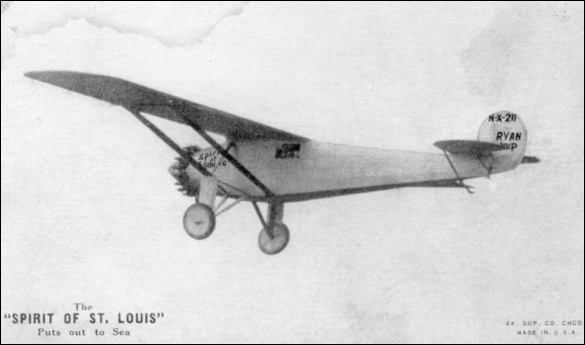

Charles Lindbergh electrified the world. At only 25 years old, he would attempt to do what many men had already failed to dofly nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. Wanting to win a $25,000 prize offered by hotel owner Raymond Orteig, Lindbergh, defying all odds, designed and built a single-engine monoplane that he named the Spirit of St. Louis. (Courtesy of James G. Davidson.)

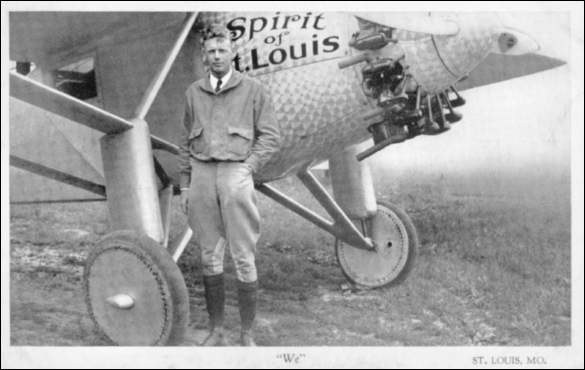

The Ryan Aircraft Company in San Diego, California, built the Spirit of St. Louis. Charles Lindbergh helped design the aircraft and lived in the hangar while supervising its construction. He began referring to himself and his plane as we. When he returned from home, he wrote about the flight in a book titled We that was republished in 1953 as the Pulitzer Prizewinning The Spirit of St. Louis. (Courtesy of James G. Davidson.)

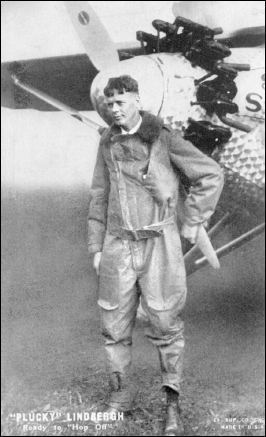

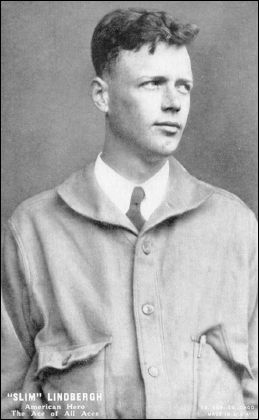

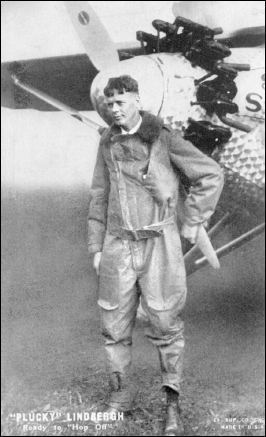

Even before his flight, Charles Lindbergh had acquired many nicknames, including Slim and Plucky. After his flight, Lucky Lindy was added. In May 1927, Lindbergh flew from San Diego to St. Louis, where he showed his investors his plane, and then he flew on to Roosevelt Field on Long Island. (Courtesy of James G. Davidson.)

There were several pilots on Long Island who hoped to take off at the same time as Charles Lindbergh. All of the competitors planes had multiple engines and a crew except for Lindbergh, who chose a single-engine plane and no crew. Daily, crowds came to the airport to see who might be taking off on this epic flight. Because of foul weather, it appeared everyone would be grounded for some time. (Courtesy of James G. Davidson.)

Sensing a break in the weather, Charles Lindbergh chanced an early-morning flight on May 20, 1927. At 7:52 a.m., overloaded with gas and with a crowd of 500 watching, the