Also by Steve Hendricks

The Unquiet Grave:

The FBI and the Struggle for

the Soul of Indian Country

To

Rocco Chinnici, Giovanni Falcone,

and Paolo Borsellino,

who, to borrow from the last,

died but once

while others die every day.

Carlyle said a lie cannot live.

It shows that he did not know how to tell them.

Mark Twain

Contents

Prelude

NEAR THE BASILICA di SantAmbrogio in Milan stands a column of rough stone erected by the Romans in the time of the Caesars. It is Corinthian in style, a fluted cylinder topped by leaves and scrolls. The flutes have not weathered the ages well, the leaves are chipped, the scrolls broken. On the lower part of the ruin are two holes a millennium and a half old and a hands breadthor, to the point, a heads breadthapart. The Milanesi say that if you put your nose to either hole, you can smell sulfur. Put your ear to one, and the roiling of Hells flames and the cries of its sufferers can be faintly heard. The holes were created by the horns of Satanthat is agreed. Beyond that, stories diverge. By one history, Satan came to Milan to lure Saint Ambrose, patron of the city, into deepest sin, but Ambrose would not be tempted, and in a fury il Diavolo sunk his horns into the column. Another story says the encounter between good and evil was more muscular, that Ambrose and Satan locked arms in a cataclysmic grapple and Ambrose threw Satan off with such force that his horns were lodged in the column. Another claimcompletely scurrilous, the Milanesi will tell youis that the contest with Satan took place in the Holy Land, that its protagonist was not Ambrose but Christ, and that many years after Christ threw Satan headlong into the column, the column was imported to Milan.

In Milan a known fact is always explained by competing stories, more than one of which will be plausible. Some of the stories will be frivolous, even absurd. With time, the elements of all will mix, their separate origins becoming unclear. With time enough, even the one fact once known with certainty will become all but unknowable.

Chapter 1

A Kidnapping

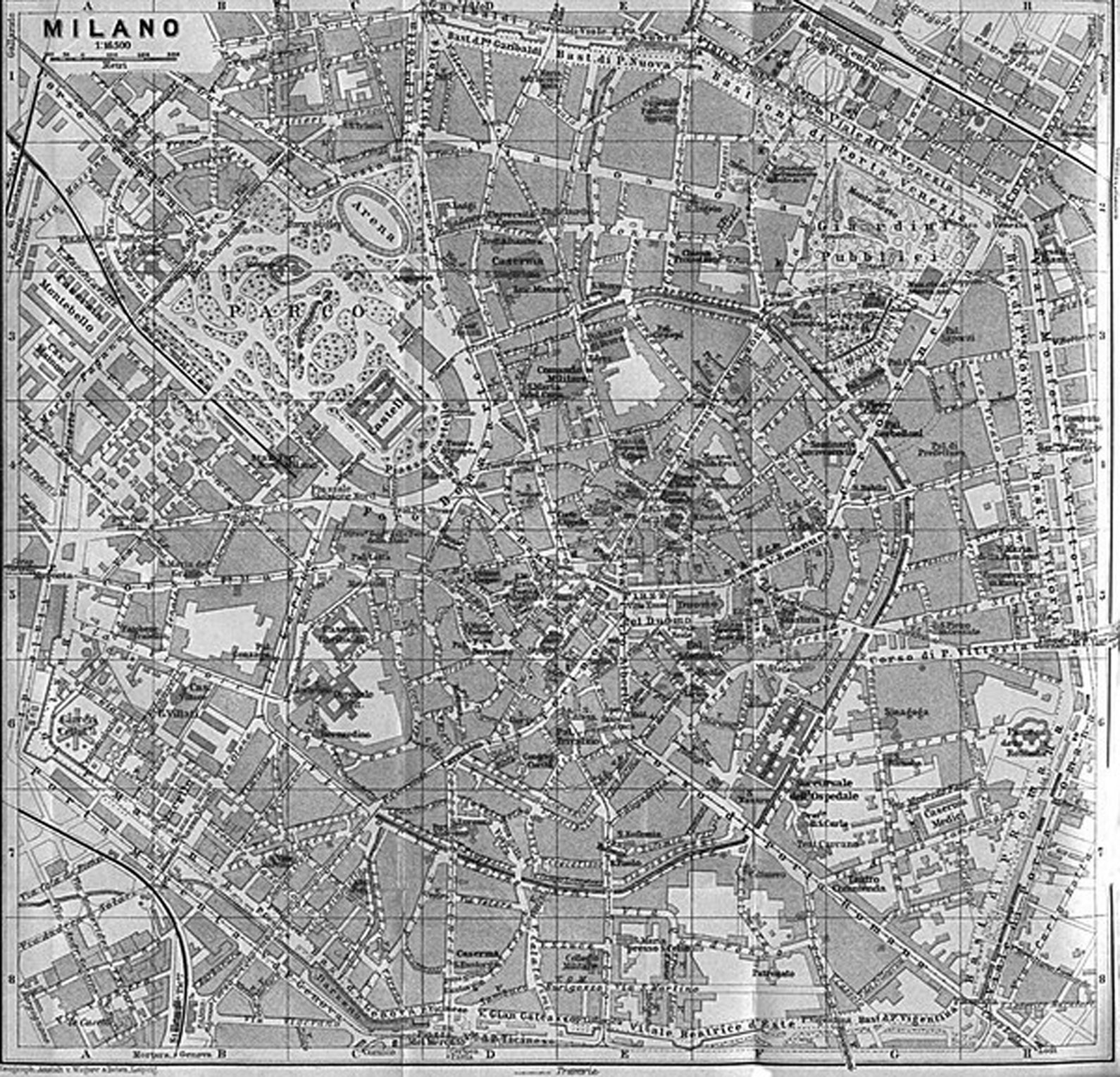

MILAN IS COLD in winter. December slips over Monte Rosa from Switzerland, down the massif of the Pennine Alps and across the wide plain of the river Po, where Milan sits exposed. The winter lifts a dampness from the rice fields around the city, and the dampness makes the chill the ruder, but the Milanesi, conditioned by two millennia of incursions, meteorological and otherwise, ignore the season. In January the sidewalk tables of the coffee bars on Corso Vittorio Emanuele II are filled with citizens and their guests, their dark coats buttoned to their necks, their hands, gloved in pliant leather, wrapped around espressos as if it were the normalest thing to be taking a caff out of doors when other liquids begin to freeze. To be Milanese is to declare the business of life more important than a mere assault from God.

It was unremarkable, then, that on a cold day in the winter of 2003 a man passed a portion of his lunch hour on an inhospitable bench in a sad Milanese piazza named Dergano. Dergano once marked Milans northern frontier but was now lost in the citys rambling, uncertain transition to suburb. The center of the piazza was asphalted, and thirty or forty cars were parked in rows orderly even by the standards of Milan, which believes itself less chaotic than the rest of Italy. Humanity, which is to say vivacity and interest, had been relegated to the piazzas periphery. There were a few benches, which had been retouched by artists of the street and which sagged. There were a few trees, which, barren this time of year, added to the piazzas sorrow. On two of the piazzas sides stood unadorned modern buildings, their fronts covered in cheap marble of the kind known to the floors of discount stores worldwide, their occupants a large chain bank and larger chain grocery. The piazzas other sides had escaped the crime of modern architecture. Their buildings were simple but charmingplastered in gentle pastels, linteled in great blocks of stone, cheerfully inferential of lives they had seen. A bakery, a wine shop, and a small mobile phonery were housed there.

The man on the bench was of the indeterminate age between youth and decline, perhaps forty. His forehead had begun to wax, his scalp to wane, but gracefully; not for some years would he face the choice of shearing what hair remained or combing it over a bare dome. His build was casually athletic but with a padding of flesh bespeaking a desk job. When he smiled, which was not often today, the left corner of his mouth tugged slightly downward, as if a piece of him refused to surrender entirely to joy. His aspect was altogether ordinary, save in one respect: he had sandy, almost blond hair, a minor oddity in dark Italy.

Colleagues knew Luciano Pironi by his nom de guerre Ludwig. That he had a nom de guerre did not imply distinction. Ludwig was a mere maresciallo , a marshal, in the Carabinieri, a branch of the Italian Army once important but no longer. The Carabinieri take their name from the horsemans sidearm, the carbine, which likely takes its name, in corrupted form, from Calabria, in Italys south. The Calabrians learned early that men with rifles light enough to be used at a gallop could give the next duchy over a good whacking. Today the Carabinieri only police Italys cities, and that only partly. The State Police, what Americans might call the National Police if they had one, share the job. Each force pursues its own cases, interrogates its own suspects, and makes its own arrests. In theory they divide their jurisdictions amicably, but sometimes one force withholds leads and witnesses from the other. There are two emergency phone numbers in Italy, 112 for the Carabinieri, 113 for the State Police. In a time of crisis, a citizen can pick his rescuer, and 113 is regarded the wiser choice. Other police agencies supersede the Cara-binieri and State Police in certain fields, like the Finance Guard, which has jurisdiction over money laundering and smuggling. The multiplicity of police is a legacy of Mussolini, who slept poorly in his ducal bed if he thought he had given one force too many guns or too much opportunity to use them. He carved off authority and built rivalries with the same fevered inefficiency with which he built oversized train stations. The multiple forces survived because they fit the Italian condition: Italy was not unified until the late nineteenth century, and then only grudgingly. Italians have never trusted their national government nor, in the main, each other. The political birthright of the Italian is suspicion.

The most visible of the Carabinieri are foot patrols. They wear uniforms of black with red stripes down their pants and white sashes across their chests that shine at a distance but are dingy up close. They patrol in pairs so that, as Italians say, there will be one who can read, one who can write. To be a carabiniere , in idiomatic Italian, is to be a martinet . That life, however, was not for Ludwig. He belonged to a unit of plain-clothed Carabinieri detectives, the Raggruppamento Operativo Speciale, the Special Operations Group, which had been created in 1990 to combat the Mafia and terrorists. In Milan, the ROS was concerned mainly with terrorists. The ROS might almost have been considered elite, except that little that was attached to the Carabinieri bore elitisms happy stigma. Hence the noms de guerre, originally adopted to make it harder for criminals to harm lawmen but maintained, in part, to give an air of importance to a job that lacked it. Luigi had become Ludwig because of Teutonic origins: his mother was German, his father Italian; German had been his first language. He had colleagues who had taken the names Hyena and Brasco, as in Donnie Brasco, the undercover FBI agent played on screen by a virile Johnny Depp. Ludwig, shading to the commonplace, suggested a calmer temperament.

Next page