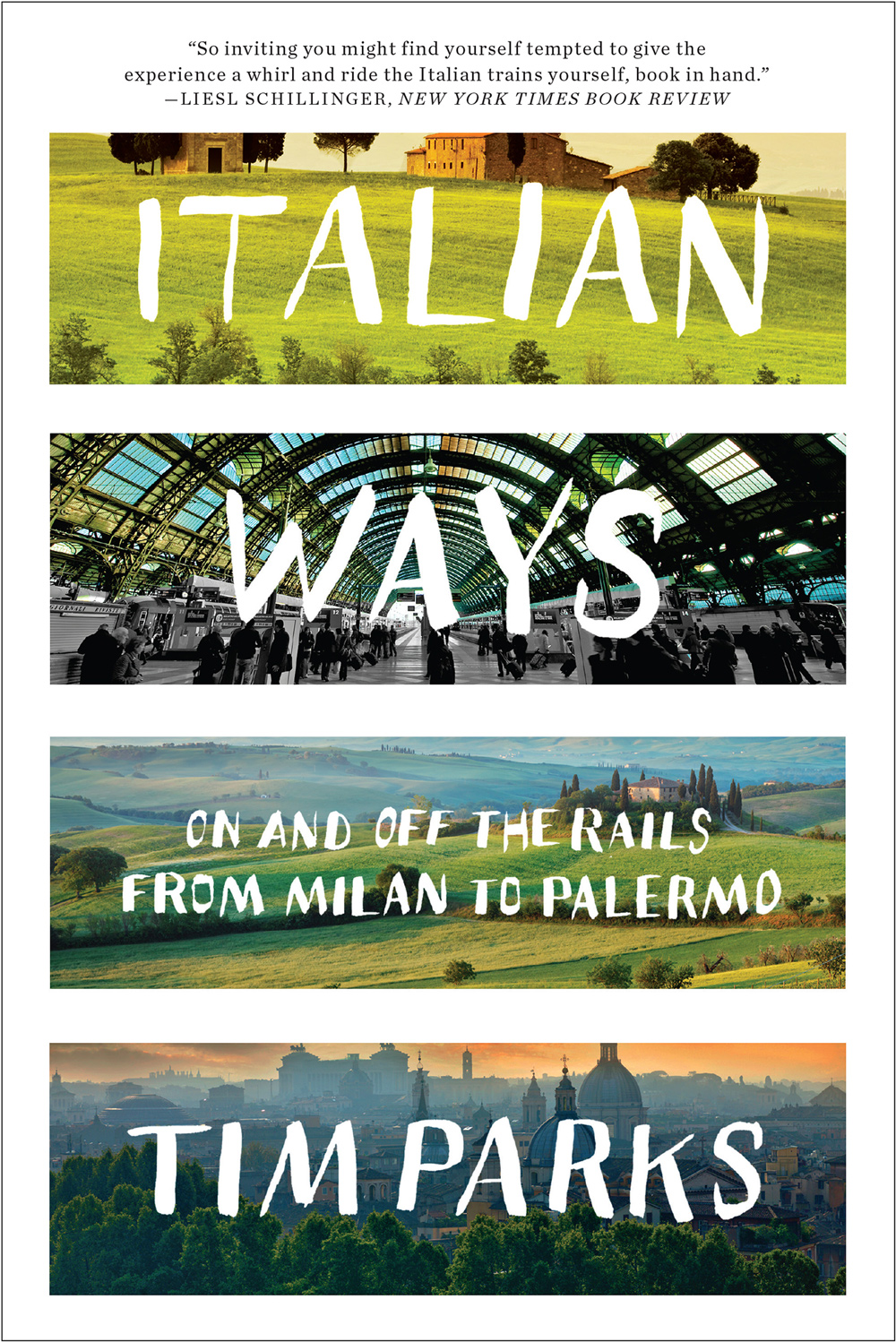

ITALIAN WAYS

ON AND OFF THE RAILS FROM

MILAN TO PALERMO

TIM PARKS

For all those who love to read on trains.

CONTENTS

A TRAIN IS A TRAIN IS A TRAIN, ISNT IT? PARALLEL LINES across the landscape, wheels raised on steel, the power and momentum of the heavy locomotive leading its snake of carriages through a maze of switches, into and out of the tunnels, the passenger sitting a few feet above the ground, protected from the elements, hurtled from one town to the next while he reads a book or chats to friends or simply dozes, entirely freed from any responsibility for speed and steering, from any necessary engagement with the world hes passing through. Surely this is the train experience everywhere.

Yet only in India have I been able to stand at an open door as the carriage rattles and sways through the sandy plains of Rajasthan. The elegant melancholy of the central station in Buenos Aires, designed in a French style by British architects, its steel arches shipped from distant Liverpool, has much to tell about Argentina past and present. Certainly the history and zeitgeist of Thatchers and then Blairs England could very largely be deduced from the present confusion of the countrys overpriced, clumsily privatized, manifestly unhappy railways. In America the lack of investment in train travel speaks eloquently of a country always ready to appear righteous but pathologically averse to surrendering car and plane for a more eco-friendly, community-conscious form of mobility.

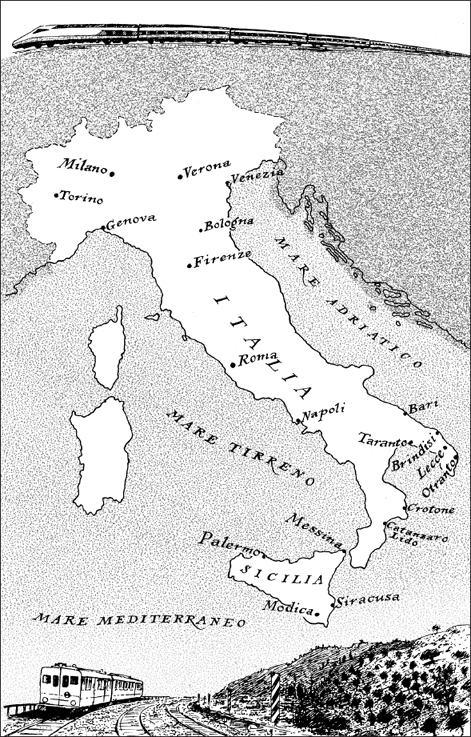

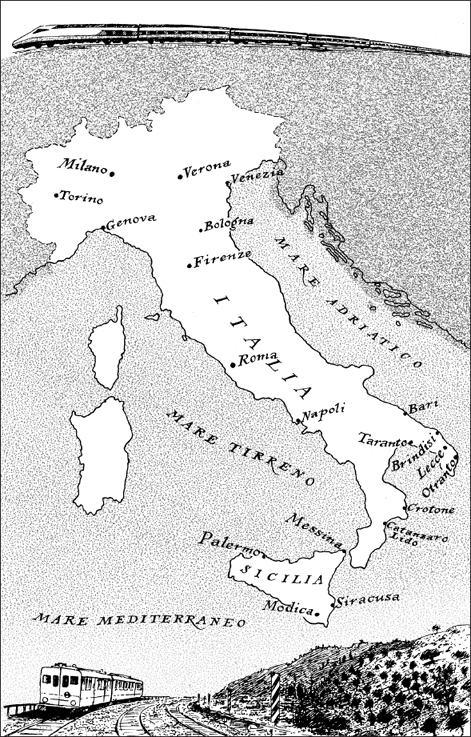

The train arrived in Italy in 1839 with four and a half miles of line under the shadow of Vesuvius from Naples to Portici, followed in 1840 by nine miles from Milan to Monza. Borrowing from the English, the Italians coined the word ferrovie , literally ironways. Unlike the English they had little iron for rails, almost no coal to drive the trains, and only a fraction of the demand for freight and passenger transport that the English industrial revolution had generated. It was hard to fill the trains and harder still to run them at a profit. But where business wasnt good there was politics. The Risorgimento process that aimed to unite the peninsulas separate, often foreign-run states into a single nation was in full swing; all sides in the struggle understood that rapid communication would encourage and later consolidate unification. There were also military considerations. What better way to move a large body of men quickly than in trucks on rails?

So railway building was almost always politically motivated, which again made the commercial side of the operation more difficult. After unification, debates over the routes of strategic lines offered a new battleground for an ancient campanilismo , that eternal rivalry that has every Italian town convinced its neighbors are conspiring against it. Amid all the idealism and quarreling, by the end of the nineteenth century the railway unions had become the biggest and most militant in the country and hence would play an important role in the struggle between socialism and Fascism; after the Second World War they became central to the governments policy of keeping the electorate happy by creating nonexistent jobs and awarding generous salaries and pensions. More than one person has claimed that the whole history of Italy as a nation-state could be reconstructed through an account of the countrys railways.

But this is not a history book, nor exactly a travel book, though there is travel and history in it. Nor did I plan it and set to work on it in quite the same way I did with my other books on Italy. A few words of explanation are in order for the passenger who has just purchased his ticket and climbed on board Italian Ways .

My first sight of Italy came through the windows of a train. It was dawn on a summer morning in 1974. I had been dozing through France and woke near Ventimiglia to see the light graying on the Cte dAzur as we flew over viaducts and through tunnels. It wasnt the first time I had seen palm trees, but one of the first. I was nineteen and traveling alone on an InterRail pass. Having met two likely Lancashire girls who had it in their heads to see the Byzantine mosaics in Ravenna, I tagged along with them, not appreciating that such a cross-country trip ran absolutely against the grain of Italys topography and traffic flow; only a masochist would attempt to get from Ventimiglia to Ravenna by rail.

A few days later, on the platform at Firenze Santa Maria Novella, I bought a flask of Chianti with two German boys, the kind of wine they sell in bellied bottles with straw aprons, and after no more than a couple of swigs passed out, to wake up in my vomit three hours later in the corridor of an evening Espresso to Rome. Those were the days, fortunately long over, when cheap wine might be cut with almost anything. I spent that night in a sleeping bag on a patch of grass outside Roma Termini with thirty or forty other travelers, and while I slept, my shoulder bag, which was looped around my neck, was razored away; when I woke I had lost my shoes, guidebook, and passport but not my wallet, which was in my underpants. That morning my bare feet burned on the scorching tar as I began the first of many bureaucratic odysseys in this country that years later would become my home. Of the language I knew not a word. These were rites of passage; I had been delivered into my Italian future by train.

I have now lived in Italy for thirty-two years. There are plateaus, then sudden deepenings; all at once a corner is turned and you understand the country and your experience of it in a new way. You could think of it as a jigsaw puzzle in four dimensions; the ordinary three, plus time: you will never fill in all the pieces, if only because the days keep rolling by, yet the picture does seem more complete and above all denser and more convincing with every year. Youre never quite a native, but youre no longer a stranger. So just as my knowledge of Italian literature has slowly extended from the novels of Natalia Ginzburg and Alberto Moravia, which I read to learn the language, underlining every word, back through the masterpieces of Svevo and Verga, Manzoni and Leopardi, then farther and farther into the past until I was finally ready for Dante and Boccaccio, likewise my knowledge of le ferrovie italiane has extended and deepened and intensified. Its not a question anymore of liking or hating them; these ironways are family.

At first train travel was just a chore. In 1992 I gave up language teaching at the University of Verona for a career track job at a university in Milan. With small children we didnt want to move to the big city, so I was condemned to commuting two or three times a week. I had no idea then that Italian railways were hitting an all-time low and even less knowledge of the reasons why that was so. I just suffered and of course laughed, since laughter is preferable to tears, and more sustainable. But often I enjoyed too: for to move on rails through a beautiful landscape is always a pleasure, and strangely conducive to reading, which is a major part of my life. Plus there was this: the deeper you get into a country, the more every new piece of information, every event and discovery, arrives as a fascinating confirmation, or challenge: how can I reconcile this bizarre thing that has happened with what I already know about the place? What might have seemed trivial or merely irritating the first year you were here now enriches and shifts the picture.

Next page