O n a September evening in 1964, a branch line terminus in the north of England waited for the Beeching Axe to fall. As the last train from Carlisle pulled into the tiny terminus at Silloth, the usual diesel replaced by a steam locomotive for the occasion, passengers in the packed coaches gasped to see a crowd of between 5,000 and 9,000 people spilling across the tracks and a group of folk singers performing The Beeching Blues. The police had already ejected the local Labour Party candidate from the platform. With the train preparing to return to Carlisle, officers repeatedly removed a placard which read, If you dont catch this youll never get another one unless you vote Labour, from the front of the locomotive, which was also adorned by a wreath. The final departure was delayed, first while the police removed detonators from the rails and then as they removed dozens of teenagers sitting on the line to shouts of, Remember its your train theyre stopping as well as ours from the crowd. As the locomotive inched forward, the driver released hot steam and then hot water to clear the last of the demonstrators sitting on the tracks before the train pulled away to the sound of Brian Poole and the Tremeloes Do you love me? playing

A few weeks earlier the local MP, Willie Whitelaw, had been accosted by a constituent whose farm bordered the line. The farmer complained that if he was no longer able to see the branch train passing in the afternoon he would not know when it was time to go home for his tea. He was advised to get a watch. This was not just the loss of a local amenity, it was a fundamental alteration to a pattern of life; the old certainties steamed away to the soundtrack of the new Britain. This convenient symbolism was less significant, however, than the fact that the teenagers (the account in the Railway Magazine, founded in 1897, felt the word still required inverted commas) were as unhappy at the loss of their railway as the watchless farmer.

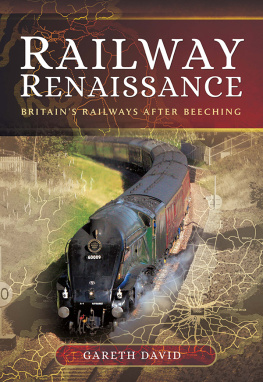

The atmosphere in which the last train left Silloth was unusually politicised and rowdy (the 1964 general election was only a month away), but similar scenes took place all over Britain during the 1950s and 1960s, as the passenger railway network contracted from around 17,000 miles in 1948 to under 9,000 in 1973. The fall in the number of stations open to passengers was even more dramatic, from over 6,500 to 2,355. Sometimes there were protests but more often the last train was mourned like the passing of an old friend, albeit one the mourners had lost touch with lately. It was not unheard of for someone who had travelled on a lines first ever train to travel on its last; people would wave from level crossing gates and enthusiasts would descend from far afield. It was not uncommon either for the last train to be barely marked, perhaps an epitaph chalked on the locomotive by its crew and a dreary sense of resignation among the few remaining passengers. The name of Dr Richard Beeching has become so indelibly associated with this process that over thirty years after he left the British Railways Board (BRB) the BBC could use it in the title of a sitcom set on a rural branch line in the early 1960s, Oh Dr Beeching!, and be confident the public would recognise it.

Beeching joined the British Transport Commission (BTC), the publicly owned body with responsibility for the railways, in March 1961 and became chairman on 1 June. When the BTC was replaced by the BRB on 1 January 1963, Beeching became its chairman, remaining in the post until 1 June 1965. The context for Beechings appointment was the railways burgeoning deficit. Operating profits had declined steadily since 1952, becoming losses in 1956. In 1962 that loss was more than 100 million and interest on the railways debts added some 50 million to that figure (even though interest payments on much of their debt had been temporarily suspended). Under Beechings chairmanship, the BTC and BRB closed 2,479 route miles to passengers (less than a third of the total contraction). In March 1963 the BRB published The Reshaping of British Railways, or the Beeching Report as it soon became known. At great length the report expounded what was in essence a very simple message: the railways had to concentrate on carrying the traffic for which they were best suited with increasing efficiency, while cutting out that which did not pay. This meant investing in the transport of large loads over long distances, while withdrawing many stopping-train passenger and pick-up freight services (in other words local services stopping at every station), and closing lines on which no other traffic was carried. In short, the railways should behave like a business. Beeching made a number of positive recommendations, most notably investment in freightliner trains, which he hoped would allow rail to retain some general merchandise traffic by offering a long-distance service combined with collection and delivery by road. Nevertheless, the parts of the report which attracted the most attention were the list of 2,363 stations to be closed, 266 services to be withdrawn and seventy-one to be modified, and the accompanying map which showed that roughly a third of the passenger networks route miles would go. By 1973, 31 per cent of the route mileage open to passengers in 1962 had closed; slightly more than half of this was achieved by the end of 1965. By this time, studies set in motion by Beeching had identified a network of 78,000 miles, less than 5,000 miles of it open to passengers. This implied nearly twice as many closures again as Beeching had presided over. These proposals were never implemented.

As a literary text, the Beeching Reports pages of alphabetically ordered stations to be closed have the mournful look of names on a war memorial. This sombre list immediately inspired a Guardian editorial, entitled Lament, which utilised some of the more interesting station names and ended Yorton, Wressle, and Gospel Oak, the richness of your heritage is ended. We shall not stop at you again; for Dr Beeching stops at nothing.

The contraction of Britains railway network was well underway before the Beeching Report. Between 1950 and 1962 the passenger rail network shrank by over 3,300 miles, the rate of contraction accelerating from 1958. But the concentration of so many closures in one slim volume associated Beeching with the entire process. No other nationalised industry chairman is so well remembered: at the Lord Beechings pub in Aberystwyth; at Beechings Folly, the former Southern Railway station in Tavistock; at, among others, Beeching Close and The Beechings, housing developments on the site of the former stations at Halwill Junction, Devon and Henfield, Sussex, respectively.

These are not fond memorials but infamy. The name Beeching still arouses passion, at least in men of a certain age. When I tell people I study transport policy their eyes glaze over; when I tell them I study Beeching I am often treated to a brief lecture on my subject. By the end of the twentieth century, Beeching was typically seen as having callously ignored the social consequences of closures, falsified figures, studied the railways in isolation from transport as a whole, and was variously accused of cooperating with an anti-rail conspiracy or simply being wrong.

It is perhaps worth reminding ourselves that Richard Beeching never killed anyone; indeed, he did not close a single railway line. Individual closures had to be approved by the Minister of Transport; all Beeching did was to put forward for closure those lines which were, in his view, irretrievably unremunerative. The prioritisation of financial criteria evident in the Beeching Report was founded upon the BRBs terms of reference set out in the 1962 Transport Act. Beechings critics have generally recognised that their barbs must equally be aimed at Ernest Marples, Conservative Minister of Transport from October 1959 until October 1964, who appointed Beeching, implemented many of