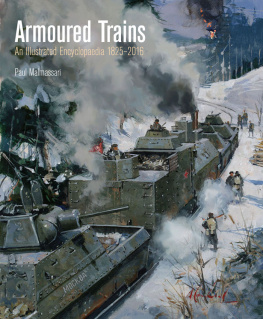

Half-title page: Close-up of the embrasure for the 57mm chase gun in the Swedish armoured train Boden, which gives an idea of the thickness of the armour.

(Photo: Sveriges Jrnvgs Museum)

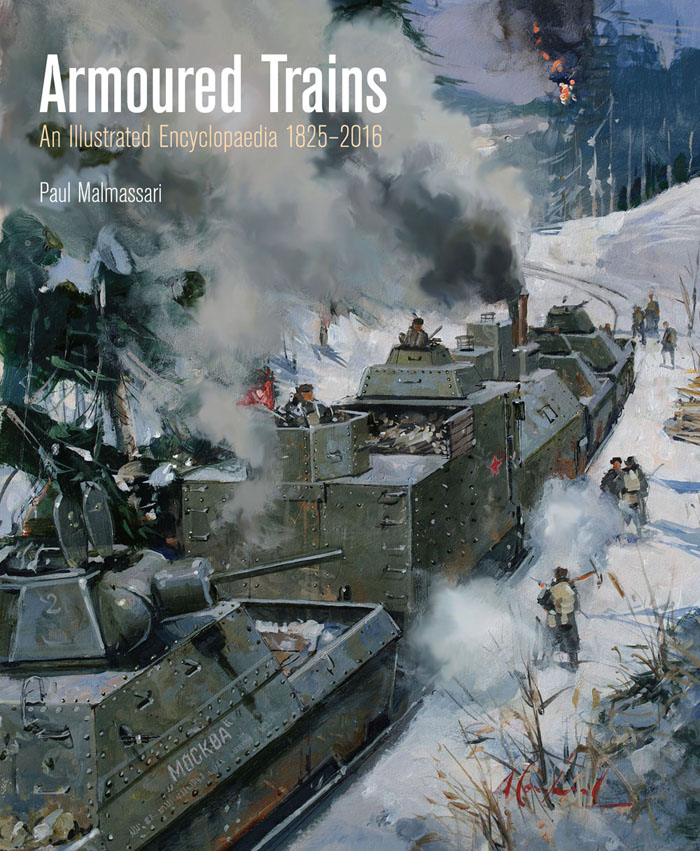

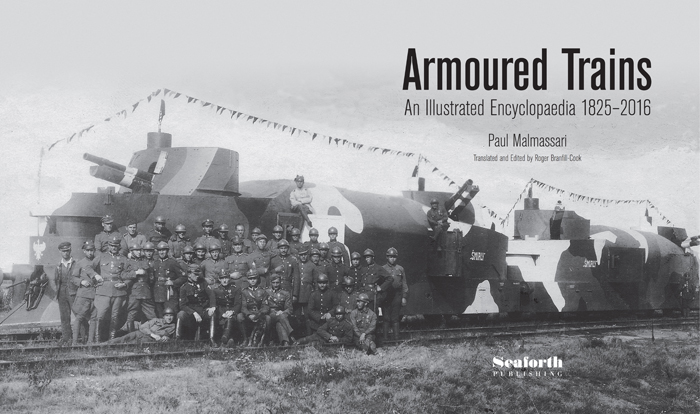

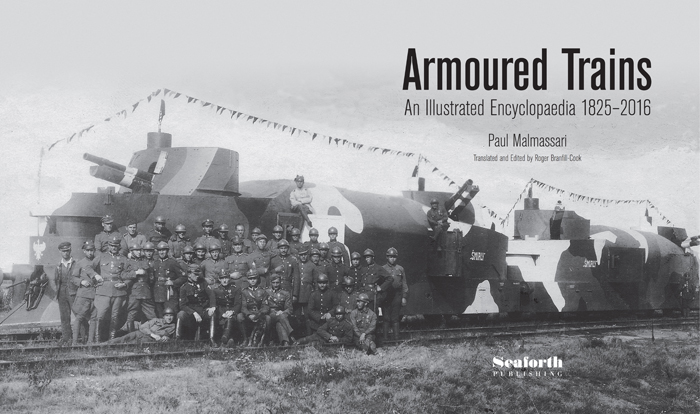

Title page: Armoured Train PP 53 miay dressed overall for Polish Army Day, on 15 August 1921. (Photo: Adam Joca Collection)

Copyright Paul Malmassari 1989 & 2016

First published in French as Les Trains Blinds 18261989 in 1989 by Editions Heimdall

This revised and expanded edition first published in

Great Britain in 2016 by

Seaforth Publishing,

An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

Email:

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84832 262 2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without either prior permission in writing from the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying. The right of Paul Malmassari to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Designed by typeset by Mousemat Design Ltd

Printed and bound in China by Imago

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

In my native France, for many of us of the generation born before the Internet and the fall of the Berlin Wall, our first meeting with armoured trains was the screening of Ren Clements classic film La Bataille du Rail (1946). The famous German armoured train depicted in the film, which has come down to us through the magic of the cinema, would have become the icon of the armoured train, had it not been cut up by the breakers torches.

Two decades later, we witnessed the destruction of another German armoured train, in the Burt Lancaster film The Train (1964), but it was the dramatic arrival of Strelnikovs armoured train in Dr Zhivago (1965) which imprinted itself on countless imaginations as it punched across our screens, with the scream of its whistle in a forest of red flags, much more than a military machine, in fact a projection of pure power.

The armoured train which we will use here in the general sense, only referring to rail trolleys, railcars and so on in specific cases is neither an armoured vehicle like the others, nor a train like the others. Neither fish nor fowl, and difficult to classify in the range of military technology, the fall from favour of this weapon probably results from this paradox. The armoured train has usually been denigrated by railway enthusiasts, who have been more inclined (in a Saint-Simonian fashion) to emphasise the social advantages of the railways. Even the famous French author Stendhal expressed the pious hope that The railway will render war impossible. For their part military historians have paid the armoured train scant attention up until recent times: traditionally they dismissed it as the poor relation of the tank, unable to manoeuvre freely, unsuited to offensive missions, and only suitable for policing duties. In sum, in Western culture the armoured train seems to be unworthy of inclusion in any line-up of major weapon systems.

However, even a brief review of the regions, the different historical periods and the conflicts in which armoured trains served will show that they were present almost everywhere, from a single, unique light armoured rail trolley, to heavy trains operating in groups, and even in fleets. Obviously, the approach to their use differs according to the nations involved and the chronological period under consideration. Despite their widespread use, especially since the end of the nineteenth century, the first concise work, written by an Italian, dates only from 1974, Since then, having taken the measure of the scope of the subject from a geographical as well as a chronological standpoint we decided to undertake this new study of the employment of armoured trains across the whole world, from the birth of the railways up until the most recent conflicts, and in as much detail as the existing sources permit.

The bibliographical references, which we have quoted in the Sources for each countrys chapter, show that many studies of the armoured trains of individual countries have been published in recent years. However, few of their authors have attempted to set them in the overall context of armoured trains or to make comparisons with other units and their employment. There are many omissions in the links between different chronological periods on the one hand, and on the other, the different means of employment according to geographical area. Historical technical material in museums and archives is widely dispersed, is not referenced on a standard basis, or is often extremely rare. In this encyclopaedia we have therefore decided to follow a logical progression for each separate country, rather than attempt to write exhaustive national histories, which only a historian fluent in the language of the country concerned will be qualified to undertake. Again, where a national work exists, we will not attempt to duplicate the text, but will restrict ourselves to the pictorial aspects.

Why Study the History of Armoured Trains?

There are three principal reasons.

Firstly, the contemporary use of these units (as in recent years in the former Yugoslavia, in Colombia, in the Caucasus and in Chechnya ) awakens our curiosity and leads us to want to link these events with historical precedents.

Secondly, armoured trains are the victims of a paradox which can be summed up as follows: in light of the common perception that, in order to defeat an armoured train, it simply suffices to cut the tracks, why is it that the armoured train has continued to be widely employed without interruption, and with varying degrees of success, ever since railways were invented? There is obviously a multitude of answers, depending on the mentality and the geography of each user nation, and on their perception of each of the threats the armoured train was intended to counter.

Thirdly, the armoured train is an inseparable part of the railway and military heritage of the nation concerned. Again, a train can be armoured for other than specific military uses, for example as official transport or for transfer of cash and specie. Various numbers of units were built, differing in quality according to the period and the armament mounted. On the other hand, the very design of the units was a reflection of the industrial capacity of the nation concerned and the doctrine for their use: the latter varied depending on the geographical area of influence, later the colonial experience, the various alliances entered into, and an evaluation of the capacities of likely opponents.

Next page