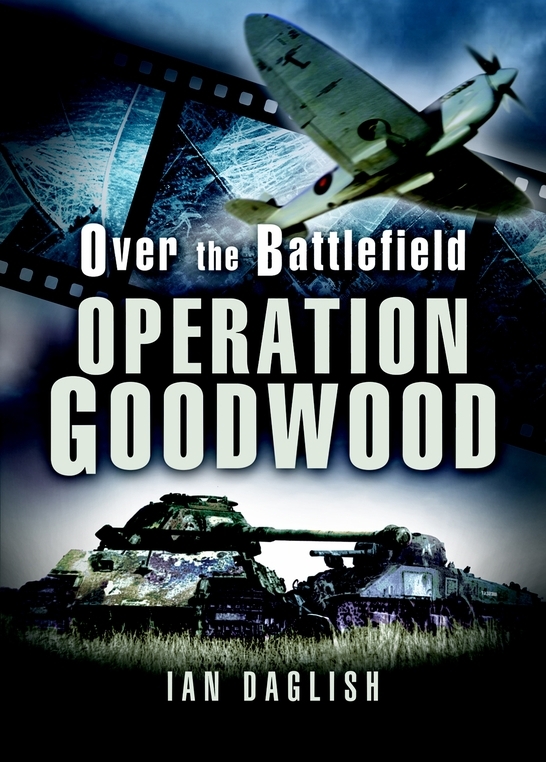

Each of the three Allied corps taking part in the GOODWOOD battle was destined to fight over distinctly different terrain. The main thrust on 18 July was to run southwards across a flat plain interspersed with small villages and orchards. Meanwhile, on either flank, more-or-less separate battles were to be fought over contrasting landscape. To the east lay wooded hills; to the west a built-up area characterized by factories, railways, rubbled town and suburbs, and crossed by a deep river.

MISCONCEPTIONS

This author was first moved to write about GOODWOOD upon visiting the battlefield and realising that his mental picture of the battleground, based on published accounts, was far from accurate. Even after reading a great many studies of the battle, the reality still held surprises.

Just as familiarity with the terrain assists understanding the battle, so can ignorance of it lead to wrong deductions. One account of GOODWOOD written soon after the war mistakenly blamed the Normandy bocage for stopping the British: It was the hedgerow country that lost Montgomery the battle The hedgerows won over the individual courage and brilliance of soldiers who had survived Africa but who did not understand the terrain in which they now fought. The writer may be entitled to his opinion that Montgomery lost the battle; some would disagree. But his comments betray a lack of knowledge of both the soldiers and the terrain. As far as GOODWOOD is concerned, only a small percentage of VIII Corps tank crews were desert veterans, and the ground was largely open. Ironically, and rarely mentioned, there were indeed some stretches of substantial hedgerow crossing the GOODWOOD battlefield; far from hindering, these served to offer the advancing British very welcome protection from German fire.

Even apparently authoritative documents have promulgated similar misconceptions. The BAOR Battlefield Tour document both state: Between the villages the ground is completely open with no banks or hedges and very few fences. (The two documents are virtually contemporary, with no indication which came first.) Little wonder that old soldiers relying on memory might omit mention of such, officially non-existent, features in their memoirs; nor that later writers unfamiliar with the actual terrain have accepted such statements without question.

THE ARMOURED CORRIDOR

The main thrust of Operation GOODWOOD was to run southward, down an open corridor between the industry and suburbs of Caen and the foot of the Bois de Bavent. Most of this was, and remains, rich arable farmland, dotted with substantial, prosperous farm complexes and the occasional small village clustered around a Norman stone church. Today the villages are larger, but the overall feel of the countryside is little changed.

Standing near the 18 July Start Line, the overall impression remains one of wide-open country. In the direction of the armoured advance, flat fields extend as far as the eye can see. Only as one moves further south does it become evident that the distant southern horizon lies on an elevated ridge. Indeed, from the Start Line near Escoville the Bourgubus ridge lies all of eleven kilometres distant, yet barely forty metres higher. This open aspect of the land east of the Orne contrasted with the dense bocage country to the west, which had caused so many unexpected difficulties in the first six weeks of the Normandy campaign.

Apart from the industrial estates of Caen which nowadays spread across the western flank of the armoured corridor, the most conspicuous change from 1944 to be noted on a summer s day is the appearance of the modern crops. Todays much-modified strains are designed to direct more of their energy into the edible crop rather than the stem; in 1944 the ripening corn stood much taller. One point which the Battlefield Tour states entirely correctly is that during the battle, the crops were shoulder high and it was hard to locate such field defences as were sited in the intervening ground. Then, as in all previous summertime battles of European history, wheat grew to the height of a mans shoulder or higher. On a largely flat battleground, this was important.

The ground is well drained. Once the two parallel waterways of the Caen Canal and the Orne River had been crossed, the armoured corridor presented no significant water obstacles. The GOODWOOD planners hoped that the two railways running across the path of the advance would similarly present little problem. This hope was to be disappointed.

The first railway, the single-track line from Caen to Troarn, no longer exists, though most of its path along the northern side of the N175 highway from Mondeville to Banneville is still clearly visible. Aerial photographs and pre-war maps failed to show that much of the length of this railway lay on a small embankment, between one and two metres, and in parts borded by ditches and hedges. This was to prove utterly impassable to wheeled vehicles, and a stiff challenge for half-tracks and the light, tracked carriers. Even tanks occasionally had their tracks damaged by crossing the metal rails, until Royal Engineers could come forward and bulldoze earth over the lines. In itself this obstacle was only a minor hindrance, but encountered at an early stage of the advance it caused hold-ups and bunching as vehicles queued for the few level crossings.