Find a full list of our authors and

titles at www.openroadmedia.com

FOLLOW US

@OpenRoadMedia

JOYCE MILTON

FROM OPEN ROAD MEDIA

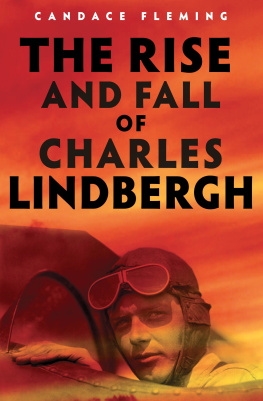

Loss of Eden

A Biography of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh

Joyce Milton

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright 1993 by Joyce Milton

ISBN: 978-1-4976-5913-1

This edition published in 2014 by Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

180 Maiden Lane

New York, NY 10038

www.openroadmedia.com

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I WOULD LIKE TO GIVE SPECIAL THANKS to my editor, Terry Karten, for her encouragement and guidance; to copy editor Sue Llewellyn, for her careful corrections and comments on the manuscript; and to my agent, Barbara Lowenstein.

This book would never have come about without the inspiration of my mother, who waved a flag to celebrate the triumph of a fellow Swedish American, and of my father, who never did get a glimpse of Lindy when he landed in Pittsburgh but returned to the airfield soon after for his first airplane ride.

ONE

Prophets

O N A LATE SUMMER DAY in the year 1900, Evangeline Land stepped off the train in Little Falls, Minnesota, and a hired a wagon to transport her trunk to the Antlers Hotel on Broadway. If any members of the school board were waiting on the platform to greet her, they must have been quite pleased with the new high school science teacher, whom they had hired sight unseen to teach five courseschemistry, physics, biology, physical geography, and physiologyall for a starting salary of fifty-five dollars a month. Twenty-four years old, Miss Land was a slight, active woman with curly brown hair and large gray-blue eyes. She was pretty but not distractingly so, and unusually well educated for a small-town schoolteacher. A graduate of Miss Liggets Academy in Detroit, she had earned a B.A. in chemistry from the University of Michigan.

There were few opportunities for women scientists at the turn of the century, and Evangeline had decided to use her bachelors degree as a passport to see something of the world beyond her comfortable middle-class neighborhood in Detroit. After reading Down the Great River, Willard Glaziers 1881 account of his search for the true source of the Mississippi, she had set her sights on Little Falls. Glaziers popular and highly romanticized narrative told how he and his party had explored the headwaters of the river, canoeing across lakes with picturesque names like Winnibegoshish, where they encountered noble copperskinned Chippewa as well as elk, bears, deer, and numberless flocks of migrating ducks, brants, cormorants, pelicans, and trumpeter swans.

Their journey of exploration completed, Glaziers party had continued downriver, stopping at a series of trading posts and rough lumbering camps before arriving at Little Falls, the first truly civilized town on the Upper Mississippi. There, wrote Glazier, a brass band saluted us with a lively air while cheers and words of welcome met us on every side. The explorers were led off in triumph to a comfortable hotel, where a delegation of townspeople, led by Moses LaFond, said to be the towns first settler, questioned Glazier about the rivers geological origins and brought, for his inspection, a collection of relics, evidence of some unknown race that had inhabited the northern forests long before the arrival of the Chippewa and the Sioux.

When she accepted the school boards offer, Evangeline imagined herself teaching science to the children of humble lumberjacks and miners, perhaps with a faithful dog to carry her books to and from the one-room schoolhouse. But two decades had passed since Glaziers visit, and progress had come to Little Falls. The Pine Tree Lumber Companys state-of-the-art sawmill was busy round the clock, and local businessmen were buying up tracts of real estate on the west side of town and building workers housing and blocks of stores on speculation. The windswept prairies to the west of town, where warriors of the Sioux nation had risen up against the whites as recently as 1861, were divided into prosperous farms. The primeval pine forests to the north and east were fast being clear-cut.

A county seat with a population of something over five thousand, Little Falls was far past the one-room schoolhouse stage, and the superintendent, probably reasoning that Miss Land was young and energetic enough to climb stairs without strain, promptly assigned her to a classroom on the top floor of the five-story high school building. The room was cramped and poorly equipped, and when winter came the winds blowing off the prairie penetrated the cracks around the windows. Evangelines test tubes and beakers were icy, her fingers stiff and numb as she struggled to prepare her classroom demonstrations. She complained about the temperature in her classroomabout 54 degreesonly to be told that this was Minnesota and she would just have to get used to it.

Back at the Antlers Hotel, Evangeline discussed her problems with a fellow boarder who also happened to be the towns most prominent attorney. Charles August Lindbergh, usually called C.A., was a remarkably

At the high school Evangeline had given up trying to reason with the administration. When her room was too cold, she took it upon herself to move her students to a vacant classroom on a lower floor. One day she was carrying a bulky piece of apparatus down the narrow staircase when she ran into the superintendent of schools. He ordered her to take the equipment back to the top floor. Evangeline, her Irish temper aroused, ignored him. The confrontation ended with her setting the apparatus down on the landing and walking out of the building, never to return.

Next page