Introduction

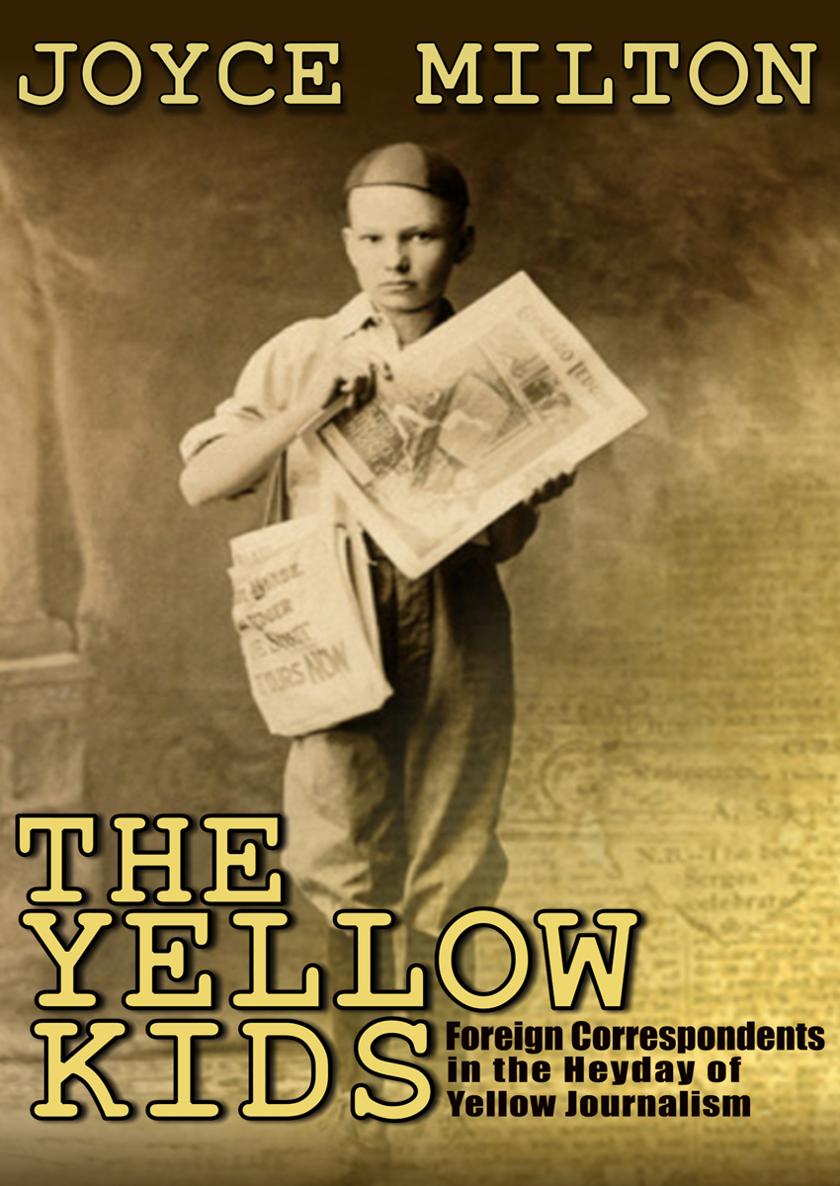

I N THE SUMMER of 1896, Hogan's Alley was the most popular cartoon comic in New York, and the most popular character in Hogan's Alley was the Yellow Kid. Hogan's Alley wasn't a comic stripthe idea of telling a story in a series of panels had yet to catch on. It was a single-frame cartoon featuring a large cast of tenement-district urchins who lampooned a different upper-class fad every week, from motorcars and golfing to the Madison Square Garden dog show. Of all the Hogan's Alley gang, the Yellow Kid was definitely the ringleaderimpudent, hyperactive and, in the eyes of some, vaguely foreign and sinister looking. He seemed the perfect mascot for the paper he appeared in: Joseph Pulitzer's New York World.

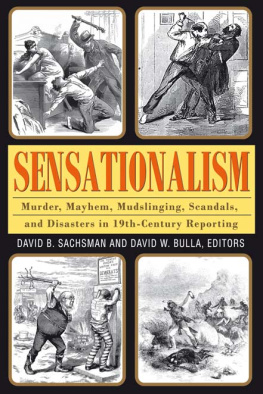

Pulitzer was not yet the universally revered figure he later became. Formerly a successful publisher in St. Louis, he had left that city under a cloud of scandal after a prominent Democratic leader was shot dead in the office of his paper's managing editor. Aside from its color comics, the World was perhaps best known for sensational headlines like BAPTIZED IN BLOOD, LITTLE LOTTAS LOVERS and, after 392 children died during a heat wave, the unforgettable HOW BABIES ARE BAKED.

Even Pulitzer's most respectable accomplishment, the raising of the money for the Statue of Liberty's pedestal, was not warmly appreciated by everyone. The World campaign had been a little too pointedly directed at the paper's immigrant constituency. At a time when immigrants were pouring into New York at the rate of one thousand a day and many native-born Americans feared that they would soon be politically disenfranchised, Pulitzer's success at organizing the foreign-born, even if only on behalf of a statue, seemed to set a dangerous precedent.

As deplorable as Pulitzer was, the most recent arrival on the New York newspaper scene was even worse. William Randolph Hearst, a Californian who had purchased the New York Journal in the fall of 1895, was heir to a fabulous fortune based on silver and gold mines, a rich kid whose politics were even farther to the left than Pulitzer's. Moreover, Pulitzer, however shrill and sensational, had ambitions to be an educator and opinion-maker. No one suspected him of seeking high office on his own behalf. With Hearst there was no such assurance. Hearst's admiration for the founding father of the Golden State, John C. Frmont, was well known, and there were many who suspected him of wanting to become the Frmont of Cubaand further, of wanting that only as a stepping-stone to the White House.

One story about Hearst that everyone knows, if only from the bowdlerized version presented in the movie Citizen Kane, is that he sent reporter Richard Harding Davis and artist Frdric Remington to Cuba in the winter of 1896-97 to report on the rebellion against the Spanish colonial government. Remington supposedly found himself in Havana with nothing much going on. He cabled Hearst: Everything is quiet. There is no trouble here. There will be no war. I wish to return. Hearst immediately cabled back: Please remain. You furnish the pictures, and I'll furnish the war.

Hearst always denied sending such a telegram, and there is no proof that he did, even though it accurately reflects his views at the time. The anecdote is misleading, however, in that it conjures up the image of the power-drunk millionaire capitalist sitting in the safety of his New York office and browbeating reluctant staffers to promote a policy they did not believe in.

Few people realize that this story was first told in a spirit of approbation. Correspondent James Creelman, who included the anecdote in his 1901 memoir, On the Great Highway, was filled with admiration for Hearst's expansionist politics, which were solidly in the tradition of Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson, and he considered the Spanish-American War one of the great triumphs of yellow journalism.

It was only through the processes of yellow journalism, wrote Creelman, that the conscience of the nation found its official voice. He continued:

The time has not yet come when all the machinery employed by the American press in behalf of Cuba can be laid bare to the public.... Things which cannot be referred to even now were attempted.

... If the war against Spain is justified in the eyes of history [and Creelman clearly thought it would be], then yellow journalism deserves its place among the most useful instrumentalities of civilization. It may be guilty of giving the world a lop-sided view of events by exaggerating the importance of a few things and ignoring others, it may offend the eye by typographical violence, it may sometimes proclaim its own deeds too loudly; but it never deserted the cause of the poor and downtrodden.

The heyday of yellow journalismor, as its admirers called it, the journalism that acts"was a period of turmoil, both in the United States and, on a smaller scale, within the newspaper business. New technologies were raising the cost of doing business, forcing owners and publishers to compete for readers by offering a product that was more entertaining, and more simplified in its approach to the news, than ever before. At the top, the competition was exemplified by the bitter feud between Pulitzer, the eccentric idealist who read Schopenhauer, George Eliot, and Shakespeare for entertainment, and Hearst, the all-American whiz kid whose ignorance of history was exceeded only by his genius for public relations.

But the era of yellow journalism was also the beginning of what Irvin S. Cobb called the time of the Great Reporter. Previously, editors and publishers had been the stars of the newspaper business, while reporting was considered a grubby dead-end job, suitable mainly for self-educated boys from poor families, black sheep, and alcoholics. By the middle of the 1890s, however, reporting had become glamorous. To a large extent, this development was brought about by the celebrity correspondent Richard Harding Davis. Davis did not consider himself a member of what he called the new school of yellow kid correspondents. Nevertheless, he created the type, both by example and through books such as his 1893 novella, Gallegher, which made a hero of the lowly city room copyboy. But the rising prestige of the reporter was also, in large part, a by-product of the competition for readers, which led to a bidding war for talent. Ambitious young menand a few young womenwho might in other times have gone into the professions, business, or the fine arts, were drawn to try their luck in the newspaper business.

![Dzhon Makdonald - The Girl in the Yellow Suit [story]](/uploads/posts/book/916411/thumbs/dzhon-makdonald-the-girl-in-the-yellow-suit.jpg)