Bernard Ryan - Stephen Hawking: Physicist and Educator

Here you can read online Bernard Ryan - Stephen Hawking: Physicist and Educator full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Infobase Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Stephen Hawking: Physicist and Educator

- Author:

- Publisher:Infobase Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Stephen Hawking: Physicist and Educator: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Stephen Hawking: Physicist and Educator" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Stephen Hawking: Physicist and Educator examines the extraordinary life and career ach

Stephen Hawking: Physicist and Educator — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Stephen Hawking: Physicist and Educator" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2013 by Infobase Learning

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For more information, contact:

Chelsea House

An imprint of Infobase Learning

132 West 31st Street

New York NY 10001

ISBN 978-1-4381-4591-4

You can find Chelsea House on the World Wide Web

at http://www.infobaselearning.com

In Aspen, Colorado, in August 1995, some 1,500 music lovers were thrilled to greet an unusual master of ceremonies at a major outdoor concert. Most of the crowd considered Aspen a favorite place not only for music festivals but for meetings of leading physicists. Now they were enthusiastically applauding a master of ceremonies (MC) who could not walk onto the stage. He rolled into view in a motorized wheelchair in which he slumped rather than sat. As their applause quieted, they knew the frail, motionless man in the wheelchair could not speak, yet he was being honored with the opportunity to introduce the musical numbers on the program.

The voice they heard was synthetic: sounds created by a computer attached to the arm of the MC's wheelchair. "This is the Siefried Idyll," said the steady monotone, "which Wagner wrote in 1870 to be performed on Christmas morning outside the bedroom of his new wife. I am here with my fiance, Elaine, and we will be married in September, so I think this piece is rather appropriate."

The MC was Stephen Hawking, the most famous scientist of his time. He was a man whose body had suffered for 53 years with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), known as Lou Gehrig's disease, but whose mind had provided answers to many of the questions about how our universe works. He was a leading physicist and the world's foremost expert in cosmologythe study of the origin, structure, and relationships to space and time of the Earth and everything beyond it.

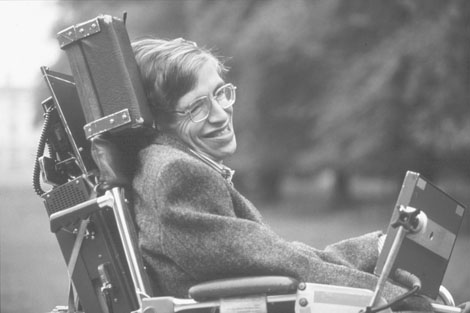

Stephen Hawking is the most famous scientist alive today.

Source: Campix.

Stephen William Hawking was born in Oxford, England, on January 8, 1942, the 300th anniversary of the death of Italian astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei. Stephen's father, Frank Hawking, was a doctor who had specialized in tropical diseases in East Africa. The outbreak of World War II in 1939 had drawn Frank Hawking home expecting military service, but authorities valued him more as a medical researcher. In that job, he met and married a medical secretary who became Isobel Hawking. Stephen was the first of their four children.

Dr. Frank Hawking and his son, Stephen, in 1942.

Source: Campix.

Following the war, Frank Hawking became head of the division of parasitology at England's National Institute of Medical Research. When Stephen was eight, his family moved to St. Albans, a prosperous middle-class town. There in 1952 Stephen passed entrance exams for the local private school, St. Albans School. Like other students, he wore a school uniform and cap. He appeared to be the kind of skinny little kid who was often teased and sometimes bullied. He had an awkward, unclear manner of speaking that his few friends dubbed Hawkingese.

Within three years, teachers at St. Albans knew that Stephen was bright, but his marks stayed only just above average. With friends who were also known as smart kids, Stephen listened to classical music programs on BBC radio and attended concerts at the Royal Albert Hall. They rode their bicycles far into the countryside, and they spent long hours playing complex board games for which Stephen invented the rules.

As a boy, Stephen lived and attended school in St. Albans.

Source: Campix.

By the time Stephen was 12, one of his friends later recalled, "I realized for the first time that he was in some way different and not just bright, not just clever, not just original, but exceptional." Another friend remembered that Stephen was always taking things apartclocks, radios, anything mechanical or electronicto see how they worked. This friend recalled that 14-year-old Stephen seldom spent much time on homework, yet "while I would be worrying away at a complicated mathematical solution to a problem, he just knew the answerhe didn't have to think about it."

Stephen and his classmates were taken on field trips to museums and factories. At one chemical plant, a scientist who had been conducting their tour took the teacher aside after Stephen had asked some questions. "Who have you got here?" asked the scientist. "They're asking me all sorts of bloody awkward questions I can't answer!"

Looking ahead toward college, Stephen decided to concentrate on mathematics and physics during his last two years in St. Albans School. (Unlike American high school students, many British students decide on a college major while in the 11th grade.) His father assured him the only future in math was in teaching. He thought his son should plan a career in medicine, which would require more chemistry courses than Stephen wanted to take. After many arguments, Stephen agreed to study some chemistry as well as math and physics in St. Albans, but not to make any commitment to medicine.

By the time he was 16, Stephen and his friends were rounding up parts from clocks and a telephone switchboard to build their own computer. Stephen's mind worked out the design, while his pals, whose hands were better coordinated than his, took care of assembling the machine. They named it the Logical Uniselector Computing Engine (LUCE) and provedas a local newspaper, the Herts Advertiser, reportedthat it could answer certain mathematical questions. (The LUCE would be a valuable museum item today if only a computer teacher at St. Albans School had not tossed into the trash a box marked LUCE. It contained what he thought was just a mess of old wires and transistors.)

Stephen wanted to follow in his father's college footsteps by going to University College, one of 35 colleges within Oxford University. To get in, he had to pass two days of entrance tests: two exams in physics, two in math, and one in world issues and current affairs. Each exam lasted two and a half hours. Then came two sets of interviews. The first was with four deans and tutors who mainly wanted to find out what kind of person the applicant was. The second was with a specialist who wanted to find out how much he knew about physics.

Within two weeks, Stephen was accepted for entrance at Oxford in October 1959. He did not know that he had received a 95 percent grade on both physics tests and only slightly lower marks on the other three exams. He did know, however, he was offered a scholarship.

At 17, Stephen Hawking was one of the youngest students at University College, Oxford University's oldest college, which dates from 1249. No friends from St. Albans went with him. Many other students at Oxford had performed military service before college and were several years older than he was, so Hawking's college social life was lonely; college work, as far as he was concerned, was a bore.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Stephen Hawking: Physicist and Educator»

Look at similar books to Stephen Hawking: Physicist and Educator. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Stephen Hawking: Physicist and Educator and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.