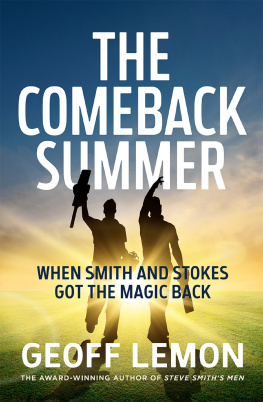

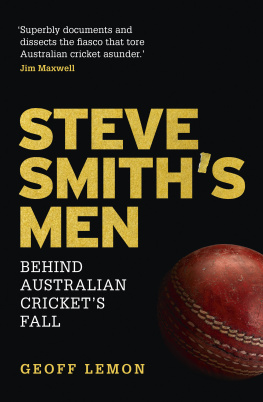

Geoff Lemon has covered cricket since 2010, for outlets including the ABC, BBC, Wisden Almanack, The Guardian, The Cricketer, The Saturday Paper and ESPNcricinfo. He has worked on radio and television in Australia, England, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Sri Lanka, the Caribbean, Ireland and the UAE, and hosts cricket podcast The Final Word. His writing outside sport appears in Best Australian Stories, The Monthly and Meanjin. His books include essay collection The Sturgeon General Presents, collaborative novel Willow Pattern, and poetry collection Sunblind. His last book, Steve Smiths Men, was named Wisden Book of the Year, MCC & Cricket Society Book of the Year, Cricket Writers Club Book of the Year, and was shortlisted for The Telegraph Cricket Book of the Year and the Mark & Evette Moran Nib Literary Award.

DRUMMOYNE OVAL IS a long, long way off Broadway. Not the actual road in Sydney named Broadway, although its not on that either. Its the cricket ground version of visiting suburban parents. Quiet, sedate, the kind of joint where theyre pretty rich but would only ever call themselves comfortable. Its lush Moreton Bay figs sprawling out limbs like drunken uncles, oaks and eucalypts on parade, the oval sunk into parkland, bounded by a neat little scoreboard and a neat little pavilion. All grassy banks and sea air. Its right on the harbour, that nourishing swathe of water that makes property prices shoot with endless vitality towards the light. A short skip down the shoreline is Malcolm Turnbulls waterside residence, and he used to pop in for official visits as prime minister to see the Governor-Generals XI.

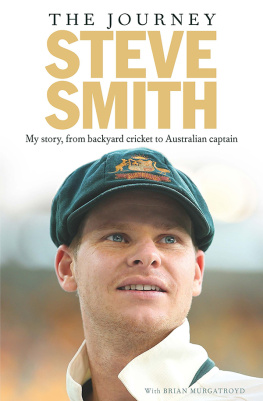

In October 2019, Steve Smith was the only former national leader hanging out at Drummoyne. A year and a half since being sacked as Australian captain, he had spent most of the second day of a Sheffield Shield match making a typically bloody-minded hundred for New South Wales, content to stay in the rhythm of a long slow innings on a low bland pitch. On resuming the following morning he had been knocked over by Shane Warnes new favourite bowler, a young Tasmanian named Riley Meredith, who had bent a delivery at pace towards the leg stump. With the stride that Smith takes across his crease to face up, the ball had somehow hooped back between his legs to hit timber.

He would have felt some disappointment, but the surroundings didnt exactly reflect intensity. In contrast, his previous 18 months had been full on. The first year had been spent in the wilderness, suspended from the cricket world that was all he had known since adolescence, after players under his command were caught sandpapering the ball during a Test against South Africa in Cape Town. The strength of anger and bleakness of disappointment from a broad section of Australians had surprised almost everyone. First fell Smith, his deputy David Warner, junior batsman Cameron Bancroft, then their coach Darren Lehmann. An investigation into the teams cheating was smothered even as a broader cultural review was commissioned, which later returned damning results. Half a dozen senior administrators eventually followed the players out the door.

Smith was banned from all Australian national and domestic teams for a year. His 2018 Indian Premier League contract got cancelled, and he was unlikely to be welcomed by the England & Wales Cricket Board, Cricket Australias close ally. He spent his suspension wandering the world like a banished rnin, assuaging shame through T20 service to regional shguns like the Toronto Nationals, Barbados Tridents and Comilla Victorians. In early 2019 he needed an elbow operation and months of rehabilitation before his international comeback started in May.

In most of these experiences he was paired with Warner, reluctant partners in fate. Their returns were just in time for the World Cup and the Ashes in England, where deeply partisan crowds were never going to let the sins of their biggest rival pass unremarked.

What followed has a strong case for being the most extraordinary single season that cricket has seen. Against that fevered backdrop, story after story escalated in absurdity, and central throughout were the characters of Smith, Warner and England all-rounder Ben Stokes. He too had a reputation to rebuild, and inevitably each of their sporting comebacks was framed in terms of personal redemption.

I followed those stories up and down England, watching some games from the commentary box and some from the boundary line, some from transit between other matches and some from down among the crowds. All summer, the spent-cordite smell of excitement lingered in the nostrils. There were my stories too from covering such a season, the details not visible from an audience view. The concept of spiritual restoration deserved the light of the examination table. The ideas in this book were forming before the season was done, and theyre the stories it will try to tell.

At Drummoyne on that October afternoon, memories of England felt like a distant dream. Only weeks earlier Smith had been in an Ashes cauldron, facing up against a dark Dukes ball under gloomy skies, lost in the booze-basted roar of English voices in their thousands. Now he was back home and padded up for New South Wales with a crowd in the dozens. For a player of his level it was a modest opportunity, but it was also something he had been barred from doing for so long. Now he was through to the other side. And on this side, things couldnt have been more relaxed. A gentle sunny Sunday, the shade of the overarching trees, a press conference held on the grass by the boundary with half a dozen journos yawning and holding out dictaphones.

When Smith had led the national team his media appearances usually projected antipathy, even toward the small pack of touring reporters who travelled the same miles as he did and generally were more fair and nuanced than distant newsrooms. He would be edgy or defensive about perceived insinuations, or flatly deny obvious problems. Right up until he was sacked, he deployed a trademark smirk while brushing off suggestions that his team had a behavioural problem.

Now, though, he was chill as a sponsors Zooper Dooper. He greeted each of us and smiled readily. He was open about recent exhaustion. Emotionally, physically, mentally. All of the above, he said of his Ashes comedown. I was pretty knackered by the end of it. I worked pretty hard, I spent a lot of time out in the middle. I didnt have a great deal of time off the field, if that sort of makes sense? It was a long campaign, with the World Cup as well. It was good to have a couple of weeks off and then get back home for New South Wales. So, all smooth rolling from here.

He looked like a man whod had a weight lifted. He was home, and far enough past his career resumption that it might soon cease to be a talking point. He was a guaranteed pick for three Australian teams, with a satisfyingly full but low-profile home summer ahead. There was the pleasure of being back where he wanted to be, and the sense that after the tumult, things might be returning to Steve Smiths version of normal.

WHEN DAVID WARNER lit the fuse on the ball-tampering story in March 2018, nobody could have imagined the explosion to come. Hansie Cronjes match-fixing expos in 2001 and Bodyline in 1933 were the only cricket stories that compared. Even in Cape Town on the evening itself, after Steve Smith admitted to cheating in pursuit of reverse swing, those of us reporting at the ground didnt anticipate the intensity of public anger. The offence was scuffing a cricket ball, not consorting with criminals or endangering lives. But its dishonesty and hypocrisy, after decades of Australian players lecturing others while exhausting their own goodwill, meant that supporters blew up even more than opponents.