Geoff Lemon superbly documents

and dissects the fiasco that tore

Australian cricket asunder.

JIM MAXWELL

Typical Geoff Lemon writing.

Evocative. Sad. Funny. Insightful.

Revelatory. Bloody brilliant.

PETER FITZSIMONS

Geoff Lemon interviews Patrick Cummins at the Wanderers, Johannesburg, March 2018. (Photograph: Adam Collins)

About the Author

Geoff Lemon has covered cricket as a writer and broadcaster since 2010, including touring with the Australian mens and womens teams since 2013, for outlets including the ABC, BBC, Wisden Almanack, The Guardian, The Cricketer, The Saturday Paper and Cricinfo. He has worked on radio and television in Australia, England, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Sri Lanka, the Caribbean, Ireland and the UAE, and hosts cricket podcast The Final Word. His writing outside sport appears in places like Best Australian Stories, The Monthly and Meanjin. Hes editor of one of Australias oldest literary publications, Going Down Swinging, and formerly directed the National Young Writers Festival. His previous books were the essay collection The Sturgeon General Presents, collaborative novel Willow Pattern, and poetry collection Sunblind.

Contents

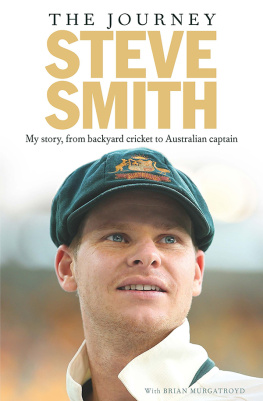

Australias 45th Test captain has always been more ice than fire. But after yanking his helmet off, raising both arms, and turning through a slow circle to every section of the Gabba, Steve Smith found he needed something more to express what was raging through him, a torrent of emotion seeking release. He faced his teammates in the grandstand, screamed an affirmation whose words were unimportant next to their expression, and beat his clenched fist against his chest as though hammering in a marker.

The first Ashes Test of 2017 wasnt the first time hed done this. Nine months earlier, starting a tour of India with another century, hed reacted the same way. But overseas excursions get relegated to the back corners of pubs and attention spans, so this was new to the home-only crowd.

It wasnt just the behaviour, it was the visual. The whole impression. Smith was always called boyish, but where for others it can be a compliment, he genuinely still had the air of a kid. It didnt end with his pizza-faced teenage photos or his chipmunk-cheeked Test debut, but carried into the second half of his twenties. In his blazer at the toss, he always looked like he was playing truant from a pricey private school. When Australia lost, a friend of mine would joke that the captain wasnt allowed to stop for Maccas on the way home.

In Pune and in Brisbane, though and nowhere in between Smith pulled off his helmet to reveal a broad headband. His fair hair was soaked with sweat into a darker shade, and his previously chopped style was longer, swept to one side in something of a Brylcreem wave. He had found, dare we say it, a dash of heartthrob.

Then there was his playing style. Where once it had been flurry and flourish, this was batting by abnegation. The Gabba track was underprepared and spongy thanks to weeks of cloud and rain. Pune had been a dust-pit where balls were ragging from minute one. On both he played with Zen calm, letting turning balls beat his edge, putting close calls out of mind, evaporating risk and ignoring his opponents hour after hour. Both times, he waited until exhausted bowlers made mistakes. He pounced on every one.

In India, where Australian teams so seldom prosper, this set up a winning start to a series. In Brisbane, his first Ashes in charge, it took his team from peril to advantage. The roar from this understated player showed how much these innings mattered. The ferocity was new. It showed what it meant to have stepped up as captain. This was graduation from boy-man to leader.

Wed known he was good, but 2017 was when Smith became supreme. Three centuries in a series in India, while his main rival, Virat Kohli, barely made a run. Three more hundreds within the first four Ashes Tests. To use the bluntest metric, his batting average was now the second-best-ever at 63.75. There was no longer any doubt he was the best Test batsman in the world. One-time rivals like Joe Root were left in the dust. The streak, the dominance, were truly insane. Were watching Bradman here, said the Australian Broadcasting Corporations lead radio caller, Jim Maxwell. Watching on from the back of the box, Jim was shaking his head in disbelief.

Everyone made that comparison at some point during the summer. Of course Smith was a mile off Bradmans famous 99.94, because the old maestro had him well covered in scale: where Smith made hundreds, Bradman made triples. But Maxwells comparison was literal and technical, referring to Smiths use of feet and wrists to open up gaps in the field wherever he wanted and manipulating bowling with three different shots for each ball. It was about depth of control and the impotence of opponents. And it was about frequency: from his first hundred onward, Bradman made one every 1.75 Tests. After that summers Melbourne Test, Smith was second with 2.13.

The maddest part was that this wasnt a purple patch, no simple hot run of form. Smith was well into his fifth year making these kinds of runs. Hed zoomed up to 23 Test hundreds in 2017, catching Gilchrist, Taylor, Hussey, Mark Waugh, Boon, Harvey and Langer. There were only seven Australians ahead of him, Ricky Ponting leading with 41. He could have walked out of cricket that New Years Eve ranked as one of the greats, and he was still only 28 years old. The thought of what he could do how much longer he could prosper was enough to make a stats fan light in the head. I remember muttering it out loud at the MCG: There is no way Steve Smith wont break that record. He could catch Ponting in three years.

Barely two months after raising the Ashes trophy with a personal series average of 137.4, Steve Smith sits in the Cape Town media centre looking stark and harried under lights. He asks for a cameramans halogen spots to be turned down, literally shrinking from their glare. What a metaphor. Then a stilted confession, one that soon turns out to be half lies. World attention explodes.

He comes down from his hotel next morning with sunglasses covering dark-ringed eyes. Chris Barrett, an old-school journo from The Sydney Morning Herald, grumbles with distaste as hes ordered to pap the Australian captain with a phone camera. A couple of days later, captain no more, team polo replaced by plain white t-shirt, Smith is buried in a phalanx of bright-vested security guards hustling through Johannesburgs OR Tambo International Airport. At the other end of that flight, white t-shirt replaced by black suit, he chokes out sobs and apologies in a curtained-off airport vestibule in Sydney.

He wont be wearing his Australian uniform again for at least a year, and is banned from the captaincy for two. Contracts are torn up around the world. The previous time India toured Australia, Smith and Kohli each made four hundreds head to head. In the season to come Kohli will take the stage alone.

It is a fall of staggering proportions. In a few short weeks the Australian captain goes from best in the world to bottom of the chasm. Through it all rings one endless question. How the hell did it come to this?

You know its serious when Mluleki Ntsabo isnt smiling. The South African Broadcasting Corporation commentator is small in stature and huge in energy, beaming a high-wattage grin as he booms away in English on the main mics or Xhosa on the update line. But as I walked into the broadcast area on the third afternoon of the Cape Town Test in March 2018, he came bouncing round the doorway behind me like a rubber ball, rebounding off the far wall, his face stern as he rushed along. Did you see? he asked with urgency. Cameron Bancroft has something on the ball.