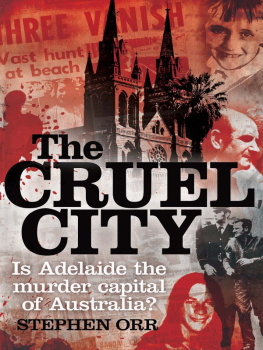

Wakefield Press

A Case to Answer

From 1988 to 1993 David Bevan was a court reporter for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and Adelaides daily Advertiser newspaper. He next covered South Australian politics for ABC Radio and Television News before joining ABC local radio. Since 2001 he has hosted the ABCs Morning and Breakfast programs with Philip Satchell, Matthew Abraham and Ali Clarke.

Before all this, he studied history, politics and English literature at Adelaide University and journalism at the South Australian College of Advanced Education.

David Bevan lives in Adelaide with his long-suffering wife, Janette, and their two children, Joshua and Ashleigh.

Wakefield Press

16 Rose Street

Mile End

South Australia 5031

First published 1994

Reprinted 2018

This edition published 2018

Copyright David Bevan 1994. All rights reserved. This book is

copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private

study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the

Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written

permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Cover designed by Liz Nicholson, designBITE

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-publication data

Bevan, David, 1964.

A case to answer: the story of Australias first European war

crimes prosecution

ISBN 978 1 74305 568 7

1. Polyukhovich, Ivan.2. War crime trialsAustralia.

3. War crimes.4. World War, 19391945Atrocities.

I. Title.

345.940238

We are not placing people on trial as a

symbolic gesture or to serve some larger

purpose of conscience. We are putting

them on trial because they broke the law.

That is the only reason people should be

put on trial.

Allan Ryan Jnr United States war crimes prosecutor

I cannot say to my children, when asked

about my attitude to such loathsome

crimes, I just forgot about it.

Australian Democrat senatorMichael Macklin

Its been a tragedy to watch. As his

neighbours said a long time ago, He is a

lovely man whatever he may or may not

have done fifty years ago. They said,

Hes a lovely old bloke and hes suffered.

Ivan Polyukhovichs lawyerDavid Stokes

Contents

Foreword

Michael David, QC

Senior Counsel for the defence

Twenty-five years ago a criminal trial unique in Australian legal history came to its conclusion. After an extensive and complicated investigation, a lengthy committal hearing and equally lengthy jury trial, Ivan Polyukhovich was acquitted of all counts of war crimes allegedly committed in the Ukraine during the second world war.

I was senior counsel for the defence. I considered it a great privilege. I use the word privilege deliberately because despite the horrific nature of the allegations the trial itself involved never-to-be-repeated issues confronting an Australian criminal court. The investigation itself included the exhumation of a mass grave in the Ukraine containing over a thousand bodies. Expert witnesses gave evidence of the aging of the bodies that were discovered for the purpose of identification. The investigators had the difficult task of taking and recording statements from aged witnesses in the Ukraine, and there were other forensic exercises such as the identification of bullets and artefacts to correctly identify the occasion. Added to this, the trial demanded the attention of expert historians who gave evidence generally about the Holocaust in the Ukraine which included the interpretation of Nazi documents obtained after the war. These issues were the fascinating background to the oral evidence given by Ukrainian and Jewish witnesses who at the time of the war lived in a village occupied by the Nazis.

Apart from its historical context, the trial produced difficult forensic decisions for the legal practitioners, both prosecution and defence. All of these matters are dealt with and described in this book.

During the entirety of the committal hearing and the trial David Bevan, despite his young age, was the senior court journalist for Adelaides leading (now only) daily newspaper, the Advertiser.

Each day he would report on the case with accuracy and fairness. The nature of the evidence was such that any report could easily spill into hyperbole. David Bevan, with great professionalism, avoided such temptation.

At the conclusion of the trial he decided to write a book about it. That work (the first edition) was published barely a year after the end of the trial. As a result of his expedience it has the advantage of what I might term dramatic contemporaneity. He has captured the immediate court-room atmosphere and the problems of all practitioners and indeed the judge. Most importantly he has managed to record the stories, outside of their evidence, of many of the Ukrainian and Jewish witnesses.

One aspect of the trial will be of great interest to those who have an attraction to both history and advocacy. David Bevan describes the dilemma peculiar to this case, in which a criminal court has to interpret the opinion of an historian. Konrad Kwiet, a leading world authority on the history of the Holocaust, is limited by rulings of the trial Judge (after objection by the defence) from giving certain historical opinions. A Case to Answer deals with this intriguing clash between historical opinion and the rules of evidence.

It is fortunate that this book was written to record almost contemporaneously the lead up, narrative and consequences of this trial. I recommend it to any practitioner or student of advocacy as well as anyone interested in the history of the Holocaust.

Foreword

Greg James, QC

Senior Counsel for the Director Public Prosecutions

Australian War Crimes prosecutions

Many years after the Polykhovich prosecution I was invited by an American University to attend a re-union of former second world war prosecutors. There I met remarkable men, such as Ben Ferencz, who helped bring to justice Nazi SS officers responsible for the murder of more than a million people. Their work began immediately after the Holocaust. Mine started several decades later, yet we shared a common purpose. This was not, as Allan Ryan Jnr states, for some larger purpose of conscience or a symbolic gesture. It was because those who were charged broke the law, in this case international law, or at least were perceived to have done so in the context of a great deal of evidence.

During my limited role in these matters of world history it was my privilege to work with fine lawyers and investigators many of whom would later take their expertise to The Hague and make a valuable contribution to the International War Crimes Tribunal. I want to record here my gratitude to the many involved, in particular to Grant Niemann my junior counsel and the Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions; to Bob Reid, the informant officer; and to Graham Blewitt who took over the Special Investigations Unit after Bob Greenwood QC resigned. Im also grateful to Michael David, QC, who went on to serve as a Justice of the South Australian Supreme Court, Lindy Powell, QC, and Craig Caldicott. They conducted the defence with skill and professionalism notwithstanding the tension and world-wide interest that a prosecution of this kind engendered after being brought so many years after the event.