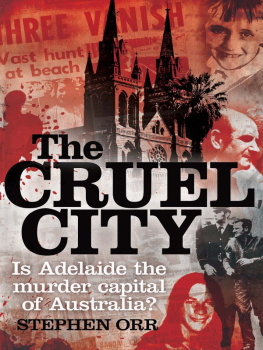

The

CRUEL

CITY

Stephen Orr is the author of three novels, the latest of

which, Times Long Ruin, reimagines the disappearance

of the Beaumont children from Glenelg Beach in 1966.

The

CRUEL

CITY

Is Adelaide the

murder capital

of Australia?

STEPHEN ORR

First published in 2011

Copyright Stephen Orr 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 509 0

Text design by Lisa White

Set in 11.5/17 pt Minion Pro by Bookhouse, Sydney

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

A version of The man who never was: The body at Somerton first appeared in The Sunday Mail (Adelaide) and The Week. Similarly, The Adelaide Review first published the piece that appears here as John Balaban and the Sunshine Caf murders.

For their help, guidance and patience I would like to thank Richard Walsh, Sue Hines, Joanne Holliman, Clara Finlay, Catherine Taylor, Janet Hutchinson, Sam and Simon at Bookhouse, and Lisa White.

Again, my wife, Catherine, held the fort while I obsessed over newspaper cuttings, transcripts and piles of books. Thanks Eamon and Henry, my sons, and harshest critics, for telling me I needed to get a life instead of tapping away on the black beast. I suspect youre correct.

Thanks to the helpful volunteers at the SA Police Historical Museum and the Old Adelaide Gaol, where Ive spent many a Sunday afternoon reading messages from the past scrawled in the mortar. Thanks also to the lovely ladies at the State Library of South Australia for continually showing me how to re-thread the microfiche machine. And yes, number 17 was broken before I used it.

Thanks to my most important sources, the citizens of the Cruel Citymy parents, relatives, friends, workmates and the dozens of people who have overheard whispers, had a strange neighbour, kept a secret for far too long or knew someone whose brothers uncles friend saw something that was never properly investigated.

This is your book, but its only part of the story.

Southern Gothic:

Death in the afternoon

I first had the idea to write, or, more correctly, to gather together the newspaper clippings, articles, books, rumours, horror stories and folklore that make up The Cruel City, in early 2009. I was sitting at home, feet up, mind blank, kids caught up in a rare, quiet game of Monopoly, when I heard a knock at the front door. I was expecting a neighbour loaded down with nectarines, or a plea for money to help rid the world of macular degeneration, but instead was greeted by a visitor with a wild beard, stonewashed jeans and an armful of manila folders.

Are you Stephen Orr? he asked.

Yes, I replied reluctantly, listening to my sons arguing over Pall Mall.

Youre writing a book about the Beaumont kids, arent you? he stated more than asked.

Yes, I managed, studying his face. Do I know you?

No. Ive been looking for you. Ive tried every Orr in the phone book but it looks like I got lucky.

Lucky? Now, Im not the sort of author who attracts deranged or obsessed fans, but suddenly I felt like John Lennon standing in front of the Dakota, chewing the fat with Mark Chapman. My only other run-in with a reader was at a meet-the-author in the Barossa Valley when an elder of the Lutheran Church stood up, told me I didnt know what I was talking about and reminded me that God was listening.

I know who took the Beaumont kids, the man at my door suddenly announced.

Really? I responded, taken aback. The thing is, Im just writing a novel, Im not trying to solve the case.

But hed already produced a small mountain of photos.

This one here, he said, this is where they were kept.

He showed me a photo of the basement of a house on the Esplanade at Glenelg, a beachside suburb of Adelaide from where the three Beaumont children went missing in 1966.

There was a name scratched into the mortarJane, the name of the eldest girland childish drawings of houses and ships with smoke coming from their funnels. There were photos of the kids, most of which Id seen in books and newspapers, pinned up on the walls, and old mattresses and bedding laid out on the ground. The stranger told me there were fingernail scratches on the walls and windows, and that the whole basement smelt of human faeces.

It was as though someone was trying to cast a local myth as a sort of Edgar Allan Poe horror story, complete with a theatrical setting and the irony of the lost kids living so close to the beach from where they were taken, listening daily to the surf, the carousel and the sounds of other children playing just beyond their screams.

They were kept in this room, and then moved, the man explained, fixing me with an intense, convinced stare, showing me other photos of other homes.

How do you know? I asked, throwing caution to the wind, stepping outside and closing the fly door, becoming intrigued with the photos.

The man explained that a friend of his had bought the house in the early 1990s and found the room intact. He didnt try to explain why the childrens abductor had left such an obvious trail of clues behind, unless he was some sort of Norman Bates disposing of his mothers house.

Its beyond doubt, he said.

Why dont you take this to the police? I asked.

He almost laughed, going on to explain how there was a network of homosexual, paedophilic senior police, judges and politicians that had conspired to keep this, and other stomach-churning instances of abuse of children, young men and others, secret. He could account for the murder of gay law lecturer George Duncan, knew the acquaintances of the Family murderer, Bevan Spencer von Einem, knew the fate of abducted girls Joanne Ratcliffe and Kirste Gordon, and many other, lesser known cases.

At this point Id had enough. I explained, again, how I was just a writer, someone who made up stories, and that, although I didnt doubt him for a moment, I couldnt see how I could help him find the Beaumont children or expose the dark side of Adelaides ruling elite.

He told me how hed approached newspapers, magazines and television current affairs programs, and how theyd all given him a wide berth. As I guessed I should.

The problem is, I explained, how could you, or anyone, prove this? How could I write anything without being sued for libel? I told the stranger that his best hope of seeking justice might be in concentrating on one or two of the cases instead of trying to convince people of some sort of conspiracy theory. You know what people are going to think, I said, carefully, taking off.

Next page