All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, New York, a Penguin Random House Company.

CLARKSON POTTER is a trademark and POTTER with colophon is a registered trademark of Random House LLC.

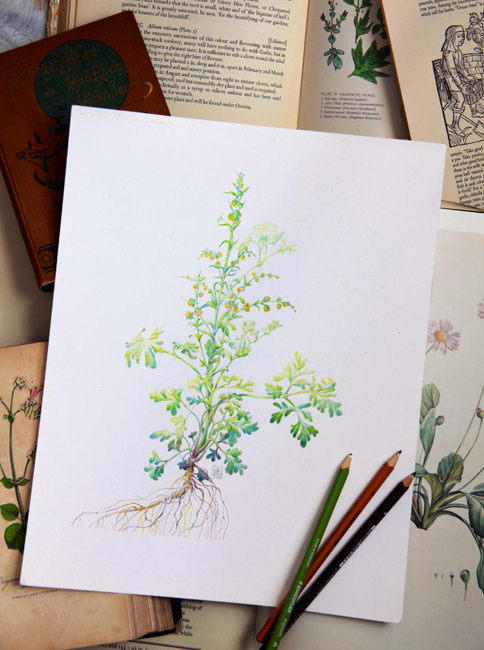

Illustrations of useful plants have been a popular subject for botanical art since ancient times. This wormwood plant was drawn for me by my friend Susan Burke.

INTRODUCTION

T ODAY I CAME indoors chilly, muddy, and wet from a mid-November afternoon spent out in the yard. It might not have looked much like a garden Id want anyone to see, covered in the twiggy detritus of recent storms and moist blankets of leaves that have lost any of the radiance they had a few weeks ago on the trees. But I knew under those dead things, one favorite group of plants, my herbs, was still thriving. The rosemary and lavender looked as fresh as May. So did the sage and thyme. Lemon balm and mint had died back a bit but still endured, a fragrant green ground cover lurking under the debris. I made tea with snippets of them and the last bits of the lemon verbena and pineapple sage from the pots by the back door. All the basil plants were gone, the victims of a hard early frost or two, but I rescued the cold-tender scented geraniums to take them back to the city to be houseplants on a sunny windowsill. Its survival of the fittest in my garden and thats one main reason I love this diverse group of useful plants. Herbs tend to be tough by nature.

Theyve developed a range of dont-eat-me strategies to ward off herbivores: bitter chemical compounds, spicy-tasting leaves, pungent scents, or even powerful alkaloids that may have a psychotropic or even poisonous effect on animals that ingest them. These defensive evolutionary traits are precisely the same characteristics that we humans value and that drew us to these plants millennia ago. We have grown to appreciate the surprising tartness of sorrel, the licorice bite of tarragon, the tongue-numbing piquancy of oregano, the sharp piney fragrance of rosemary, and the mood-altering effects of marijuana and opium. For uncountable years, these species have traveled around the world wherever civilizations took them. Some of them, such as sesame, safflower, fenugreek, and indigo, have been cultivated for such a long time that no one really knows where they are native. Others traveled the Silk Route back and forth from the Far East to Western Europe or made the long voyage to Spain from the tropical Americas with the earliest explorersor vice versa from New World to Old. Others were coddled on long sea voyages from Europe to North America to furnish the first colonial gardens with the same scents, flavors, and cures left back in England, France, and Holland. These introductions soon intermingled with selected native species highly esteemed by American Indian tribes to form a new American pharmacopoeia.

Today, each immigrant group that arrives in the United States brings their favorite herbs with them as if part of their luggage. I feel lucky to live in a section of New York City that is one of the most ethnically diverse Zip codes in the countryand one where the population still prefers to cook at home instead of ordering in. The grocery stores are always busy, and often open twenty-four hours a day to satisfy the overnight working schedules of many of the residents. The Indian market in my Queens neighborhood abundantly stocks branches of fresh curry leaves and bundles of fenugreek. A Mexican-American farmer at my local weekend greenmarket sells papalo, pipicha, tlapanche, and lemongrass to bustling crowds of ladies from the neighborhood. The Asian markets in Oakland or San Gabriel, California, feature Japanese shiso, Vietnamese culantro, Thai basil, and Chinese chives. Even a few years ago, a shopper would be challenged to find these exotic herbs in a fresh state in a U.S. market. Now we can look forward to these culinary herbs joining the ranks of once hard-to-find herbs like fresh cilantro or basil in our supermarket aisles.

Excellent herbs had our fathers of old

Excellent herbs to ease their pain

Alexanders and Marigold,

Eyebright, Orris, and Elecampane

Basil, Rocket, Valerian, Rue,

(Almost singing themselves they run)

Vervain, Dittany, Call-me-to-you

Cowslip, Melilot, Rose of the Sun.

Anything green that grew out of the mould

Was an excellent herb to our fathers of old.

Rudyard Kipling, ca. 1917

I am fascinated both by our constantly evolving and developing relationship with herbs and its long history. Its a human-plant bond that reminds me of our relationship with domesticated animals. Wherever we go, we transport our useful plants with us. In fact, the broadest definition of the word herb is a plant that people use. If you exclude all the plants we eat as food, you still obtain a huge list of thousands of species valued for fragrance, industry, oil, textiles, fibers, medical reasons, flavor, dyeing, hallucinogenic/intoxicating purposesor even poison. In this book I think of them all equally, while taking into account proper warnings for any dangerous species. But at the same time, I try not to make judgments about whether a plant is valued for its merits in the fields of science, history, or even magic/superstition. In my mind, the meaning we have placed on these plants is an essential aspect of what makes them important. To include a plant in this book, its not important whether or not the lung-shaped leaf of the lungwort cures lung ailments, but the fact that people have imbued it with such powers for centuries.

Im also very interested in learning more about the chemistry behind the herbs we love. These substancesthe flavonoids that give plants color and have antioxidant properties, the terpenes that provide fragrance and flavor, the volatile aroma compounds that make essential oils, the alkaloids that alter our mindsall are the building blocks behind the usefulness of these plants to humans. But a word of caution for those new to the study of herbs: Many experts avoid placing too much emphasis on isolating specific phytochemicals and giving them credit (or blame as the case may be) for a plants powers. These practitioners want to encourage the idea of a whole plant philosophy, where the chemistry of a certain species is complex and balanced by a blend of natural elements that make it difficult to isolate and synthesize under laboratory conditions. Still, I find the chemical links fascinating as a basic place to start my understanding of the function of herbs. I like knowing that the flavor in thyme, which Ive noticed in monarda and certain oreganos, comes from a terpene called thymol. And that the clove-like phenylpropene eugenol also appears in allspice, cinnamon, carnations, and bay. Or that the sinister group of hallucinatory nightshade plants such as belladonna, henbane, and mandrake all share scopolamine, a powerful tropane alkaloid that can cause a zombie-like state of half-consciousness, respiratory failure, and death.