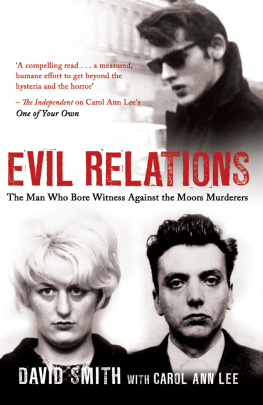

About the Authors

David Smith now lives in rural Ireland with his wife. He has four children and several grandchildren.

Carol Ann Lee is an acclaimed biographer and has written extensively on the Holocaust. Her most recent publication, One of Your Own, focused on the life and death of Myra Hindley.

Afterword

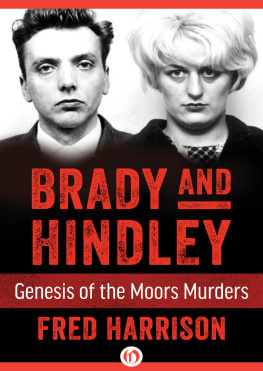

Any child born in Manchester during the 1950s and growing up in the heady days of the decade that followed will forever be affected by the crimes of Ian Brady and Myra Hindley.

As a child of that time, I vividly recall how freedom disappeared seemingly overnight in the wake of the Moors Murders case. My parents changed their way of thinking completely; during Brady and Hindleys years at liberty, when children went missing without explanation, my brother and I could no longer vanish for hours only to return when hunger got the better of us. Without exception, we were delivered and collected from school and restricted to playing within hearing distance of home. My parents warned us never to leave the street and never, ever to talk to strange men (no one thought to beware strange women). To us kids, it was just a nuisance: all at once, we couldnt go Guy Fawksing, or collect wood to make secret dens, or have any sort of adventure that involved roaming about the neighbourhood. Brady and Hindley were the end of innocence.

But Evil Relations was never going to be just another book on the case; there have been enough of those already. Instead, its been an intensely personal journey for Dave and me, and its given us both precious time to think and reflect on the most important people in our lives the ones who have guided our journey.

I want to thank our boys, Paul, David and John three fine, strong and healthy sons who originally drew us together as a couple. I want to thank our daughter Jody, who tied us together in the most wonderful of ways and made our family complete. This book is also for our grandchildren and recently arrived great-grandchildren, in the hope that no matter what they may always do the right thing.

My brother Martin is like a fourth son to Dave, and he and I have always been exceptionally close. My mother was always there for us, but this written account of our lives owes so much to my daddy and to Daves; without their friendship, we would never have met. As a young teenager, I lay safe and sound, snuggled up in Daddys bed, and asked him, What do you think about David Smith? His arm was comfortingly heavy around my shoulder as he answered quietly, Without David Smith, I might not have you.

So to our daddies, we dedicate this book.

Mary Flaherty Smith

Chapter 1

The early years were good...

Fred Harrison, Brady and Hindley (Grafton, 1987)

From David Smiths memoir:

Its 2.30 on a hot Thursday afternoon in Ireland and Im looking at a blank page. My fingers are cracked and crooked with arthritis and I find it difficult and far too much trouble to contemplate filling the page. But then, as always, a wisp of smoke appears in my mind, a thought, a feeling, somewhere to go, another corridor with no answers.

I allow the smoke to drift and dance away from me, not too far ahead and not too fast. Im beginning to think and follow... in a moment the page will fill with words and today will be gone, leaving me locked in another time. I look out at my colour-drenched Irish world, then bend my head and follow the wisp of smoke again, back to the black-and-white streets of a Manchester suburb. It carries me quickly now down the long corridor, picking up speed...

39 Aked Street, Ardwick. Im here to meet myself, nothing more than an old man thinking back the years, but my heart is in this house. It contains and stands for everything that is me, period. Once it was a place of happiness but confusion and sadness floods me as I drift back into it on that wisp of smoke, picking up the special smell of Sunday dinner and the background drone of the wireless.

On the top floor is the attic bedroom; it belongs to me but is filled with sepia-tinted photographs, mainly of a brown-eyed young man in uniform. Steep stairs lead down to the second-floor landing and to Mums room, which smells of talcum powder and is softly feminine, where little trinket boxes gleam in the sunlight. Further along the landing is Grandads room, a world away from its neighbour all pot-under-the-bed smells and spittoon boxes thick with phlegm from the old mans endless throat-clearing. Next to Grandads room is a rarity in Aked Street: a new fitted bathroom. We dont use it as often as we should; like everyone else, we have an old tin bath in the backyard which is brought in on Saturday night to wash the weekly grime from my skin.

The wisp of smoke carries me down another flight of stairs to the ground floor and the scullery at the back. All the cooking and washing are done in here, but Im looking for something else, and behind the stove I find them: Mums pint bottles of Guinness. I used to fetch these for her, racing down Exeter Street to the illegal off-licence, where theyd hand me the bottles in a paper bag. Then Id head home again, down the back entries into our yard and straight into the scullery, fast as my skinny legs would take me. Next to the scullery is a simple kitchen with a table and chair, cold meat safe and ceiling clothes maiden. Beyond it is the dining room the most used and busiest room of all, dominated by a huge wall cupboard stacked to bursting every Christmas with home-made mince pies, cakes, biscuits and other mouth-watering goodies.

The wisp of smoke evaporates, leaving me where I want to be most: the room at the front of the house, facing the street. My heart is in this room. The door is always bolted (children are not supposed to enter the parlour, after all) but nothing can keep me out. A chair, a stretch on tiptoes, a small hand feeling for the latch and...

The door to the parlour opens and welcomes me in.

* * *

Withington Hospital was originally Charlton Barlow Moor Workhouse, serving most of south Manchesters poverty-ridden inhabitants. It was converted to a hospital in 1864 and Florence Nightingale declared it one of the best, if not the best, in the country. David Smith was born within its red-brick walls on 9 January 1948 to a woman he cant remember. Joyce Hull was in her late teens when she fell pregnant to John James (Jack) Smith, a 28-year-old engineer; they never married. Joyce vanished from her sons life when he was one year old, leaving his paternal grandparents to adopt him on Valentines Day 1949. It was another 20 years before the opportunity arose for David to meet his mother.

I dont know anything about Joyce, he shrugs now. Not a thing. Only that none of the family seem to have liked her, and in those days if you werent liked, it was a serious business. I dont have a single memory of her.

All she left behind were a few photographs of the two of them together. One, included here, shows them sitting with a department store Santa, while another, taken on a shingle beach somewhere in the north of England, hangs on the wall just outside the kitchen in Davids home in Ireland. On both, dark-haired Joyce holds her warmly swaddled baby close, a wide smile on her strikingly pretty face. But within months, or even weeks, of the photographs being taken, she was gone and David Hull became David Smith, the adoptive son of John Richard Smith, a commission agent, and his wife Annie.

David grew up believing that Joyce was dead: She was just a name somewhere belonging to someone far away in the past. I knew I was adopted, but Annie was always Mum to me. She wrapped me up in cotton wool so thoroughly that there was no reason for me to ever question how things had turned out. Being illegitimate wasnt a problem in my early years I wasnt some abandoned poor little bastard running loose in the squalid city streets. Besides, there were loads of illegitimate kids after the war; every family had a skeleton in their cupboard. The only Mum I ever knew showered me with love and spoiled me rotten. Anything I ever needed or wanted was mine, I didnt even have to ask.