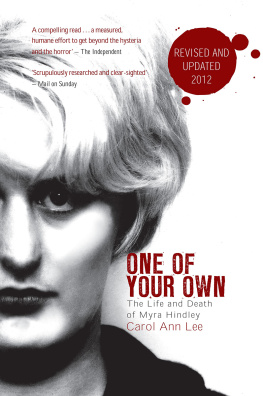

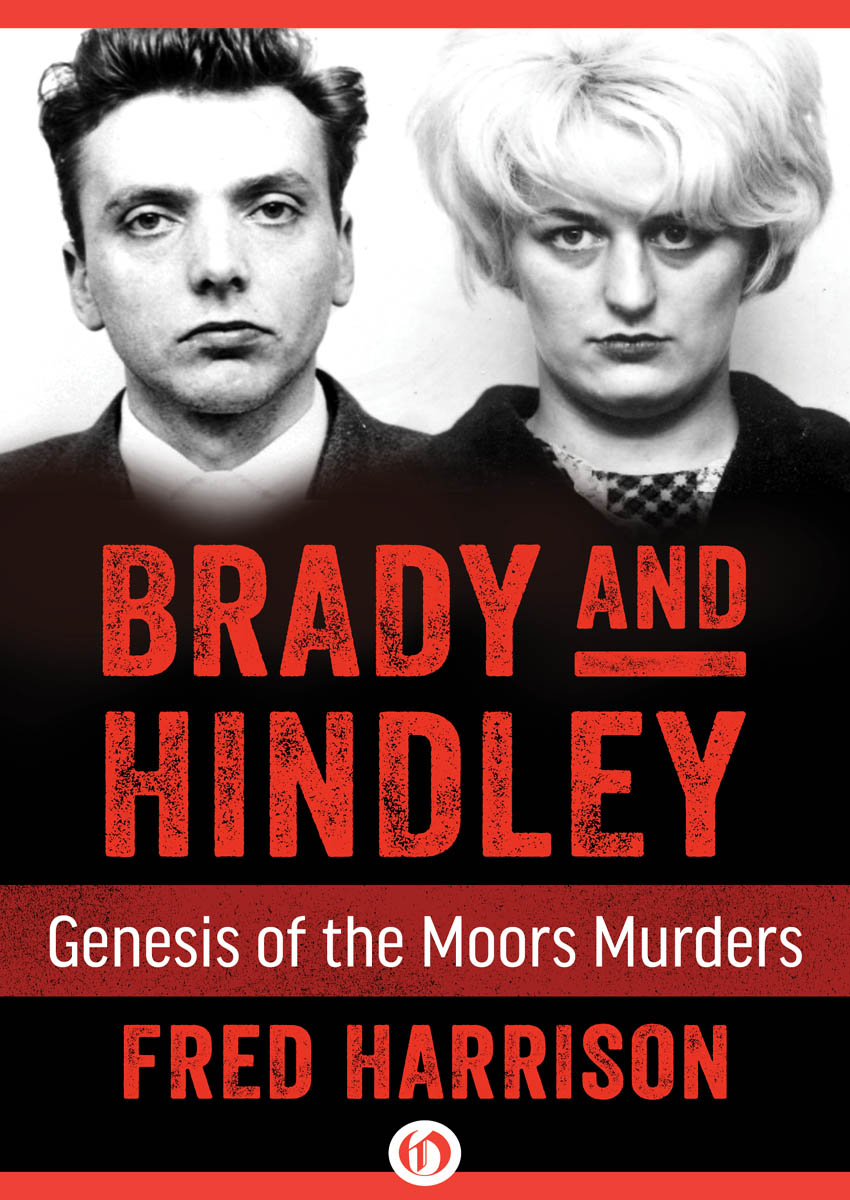

Brady and Hindley

Genesis of the Moors Murders

Fred Harrison

Contents

Acknowledgments

My thanks are due to Joseph Heller and Jonathan Cape Limited for permission to quote extracts from Catch 22 and to the Sunday People for permission to reproduce the drawing of Ian Brady by Bob Williams.

PART ONE

Genesis

PART TWO

Consecration

PART THREE

The Cult

PART FOUR

Confession

CHAPTER ONE

Psychopath

It was not an auspicious Sunday. Cold westerly winds had bellowed up the Clyde during the night, and the news vendor outside the gate of Rotten Row Maternity Hospital had repeatedly to stamp his feet on the frost-encrusted pavement to keep his blood circulating. The front page headline of the Sunday Pictorial attracted most attention: Mona Tinsleys Spirit Led Her Slayer to Gallows. The police, desperately trying to solve the brutal murder of a 10-year-old girl, resorted to the use of a spiritualist to help them to track down the killer, Frederick Nodder.

Margaret Stewart, a 28-year-old tearoom waitress, gave birth to her illegitimate son on January 2, 1938. She christened him Ian Duncan Stewart. He was never to know his father. The unmarried mother rented a room in Caledonia Road, in the Gorbals, a tough inner city slum in Glasgow. But within a few months she realised that she could not cope with both a baby and a job. She advertised the need for someone to nurse her son, and Mrs May Sloan responded. She and her husband John loved children: they had two sons and two daughters of their own, all of them older than Ian. Between them they provided the little stranger with the security of a clean home, a brown-stone tenement in Camden Street.

Ian grew tall, thin and sallow. He was intellectually bright, but reluctant to apply himself to the full at Camden Street Primary School. He joined in the rough-and-tumble of street games, but he was shaping up into a lonesome character. He knew he was different. He did not know why; it was just a feeling that, somehow, he did not belong. He emphasised this apartness for the first time at Sunday school. The teacher asked: Does everybody believe in God? No, came the reply from the sole dissenter. Ian was 5-years-old. Looking back on that incident, he identified it as the first occasion on which he chose to differentiate himself from his peers.

Ians early experiments in cruelty were no different from the behaviour of many children who take delight in making animals suffer. He threw cats through windows to see if they could survive 30-foot falls and he killed his share of birds. But the little boy was not yet beyond the pale.

He was eight-years old when he suffered his first trauma. He was walking along one of the cobbled streets near home on a cold and frosty morning. His attention was attracted by a commotion, and he ran to see what the excitement was all about. Behind a gathering crowd was a sight of suffering that left its mark indelibly printed on the boys emotions. A giant Clydesdale, which was pulling a draymans cart, had slipped on the cobbles and had broken a bone. It was in agony. Ian felt helpless as the majestic beast appealed to him for relief from the searing pain: it stared at him, screaming silently through two large pools of water-filled eyes. Ian could not stand the sight of the stricken beast. He ran away, tears streaming down his cheeks.

The overriding emotion in Ian Stewarts early boyhood years was one of a strange emptiness. The Sloan family kept him warm and well-fed, and life revolved around the routines of school and play, seasonal festivities and pocket-knife adventures in the streets. The tenement blocks marked the territorial boundaries of his world, protecting his body and yet, in some indefinable way, imprisoning his soul. Then, during his ninth year, Mrs Sloan announced a treat: the family was going to the country for the day. She packed sandwiches, and they set off for the hills around Loch Lomond. It was the fatal turning point in Ian Stewarts life.

The boy was entranced by the vast open space. He felt the mystical calls of nature all around him, and he wondered. He knew instantly that he had an affinity with whatever was out there, beckoning him, trying to liberate his soul. He felt natures power pulsing around him as he climbed, a solitary figure, higher up the hillsides. He stood motionless for an hour as the strength of nature coursed through his body. The howling wind and the thorny heather, the clouds bellowing through the heavens this was where Ian belonged. It was a spiritual experience, the origins of the boys pantheism, which affirms the unity of the gods with nature itself.

Intuitively, the boy knew that he was not one of the Sloans. They succoured him, but theirs was not his natural home. Now he had found the spiritual comfort he needed, which filled the emotional vacuum of his childhood. The formative events started to come thick and fast.

When Ian reached the age of 12, his dog became ill. He prayed to God that his pet would not die. His prayers went unanswered, which convinced Ian that there was no personal God. A year later, he discovered that he was born a bastard. It was the crushing news that confirmed that he was an outsider, and he turned his back on society. He sought fulfilment in petty crime, and escaped the realities of life in the fantasy of the cinema. House-breaking and burglary did not pay: he was caught and brought before the juvenile courts. His behaviour was treated as the tearaway misdemeanours of a working class lad from the slums, pranks out of which he would grow with the passage of time.

Then, one day, he was at the end of his school career. He scanned the job advertisements in the local Press, and finally found one that looked promising. He mounted his bicycle outside the Sloans house in Templeland Road, Pollock, an overspill estate on the outskirts of Glasgow, and rode through the Hillingdon housing estate on his way to an interview. As he turned a corner, Ian felt giddy. He dismounted, and stood in the doorway of a newsagents shop. His head was spinning. He supported himself by leaning against the newsagents window. And there it was, a green, warm radiation, not unattractive to the young man who clutched his head to try and steady himself. The features were unformed, but still recognisable. Ian knew that he was looking at The Face of Death. He did not know, on that rain-swept day in Glasgow, that this experience was destined to become the focus of his private cult; that the souls of innocent children would be sacrificed to The Face of Death. But he instantly knew that his salvation was irrevocably bound to its demands. Ill do it a favour, and like it will do, in the end it will do me favours. The bond with death was fused by that green radiation.

One of Ians first jobs was butchers assistant. He saw the sharp knife being wielded dispassionately against flesh and bone. What could be done to dead meat could be done to live flesh: on at least one occasion, he joined a gang of youths to carve up a 16-year-old boy with knives.

The fantasy of life as an outcast from a society that he despised now consumed his thoughts. He was going to be the Master criminal. In the meantime he settled for small-time housebreaking expeditions. He fell foul of the police on several occasions. After one sortie, a boy made the mistake of informing on him. Years later, when he moved to Manchester, he told the story of his revenge. He boasted that he had murdered the boy and buried him on a bomb-site in the Gorbals. Nobody believed him. The world was yet to learn that Ian Stewart was a young man who did not lie.