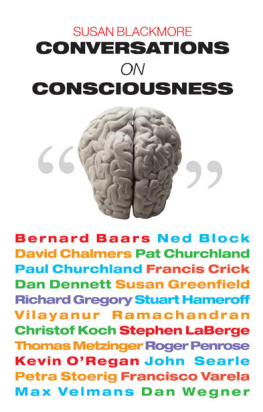

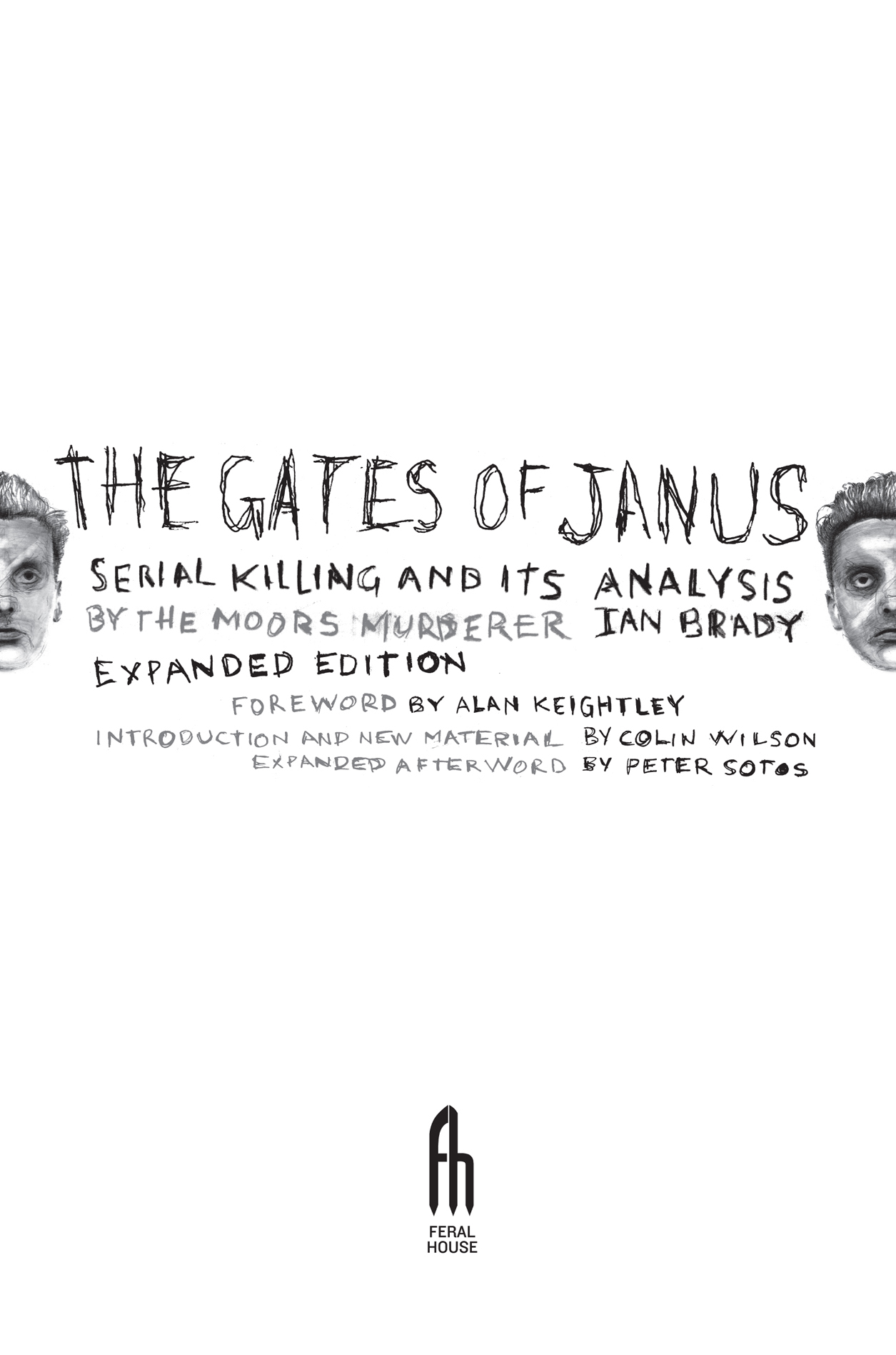

The Gates of Janus:

Serial Killing and its Analysis

Expanded Edition

By Ian Brady

The Gates of Janus 2015 by Ian Brady, Feral House

All rights reserved

A Feral House book

ISBN 978-1-62731-014-7

Feral House

1240 W. Sims Way Suite 124

Port Townsend WA 98368

www.FeralHouse.com

design and illustration by D. Collins

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

THE GATES OF JANUS BY IAN BRADY

by Dr. Alan Keightley

A s soon as I received and began to read this manuscript I knew that I had a remarkable document in my hands.

The author, who did not reveal his name to me, and whom I assumed to be a man, seemed to be offering a hunting manual for the tracking down of the serial killer by the use of psychological profiling and a study of his afterimage at the scene of the murder. Doing this successfully would be an achievement in itself. I leave others at the knife-edge of forensic investigation to judge its efficacy in the pursuit of what the author calls the greatest and most dangerous game in existence: man.

Expert profilers have, of course, already produced studies of serial killers. FBI detective Robert Ressler wrote the substantial Whoever Fights Monsters. His associate at Quantico, John Douglas, produced Mindhunters. So, whats new here?

The Gates of Janus is a book written by a serial killer about other serial killers, or, as the author himself says, a dissection of what murder is really all about from the point of view of a murderer, for a change. Criminals have written books before and classically, Dostoevsky and The House of the Dead, but the present study has a uniqueness of its own.

This leads me on to the second reason for its special character the sheer quality and intelligence of the writing and its acute observation of human behaviour. The author investigates the psychology of the serial killer by discussing a number of notorious cases, which fleshes out the bare bones of his general conclusions about profiling. Again, its true that lay authors have written high-grade books on murder. Joseph Wambaugh, Stephen Michaud and Ann Rule come to mind. They themselves were not killers, although Ann Rule knew Ted Bundy quite well according to her book The Stranger Beside Me. But Bundy remained the stranger beside her. A murderer writing on murder possesses a perspective denied crime writers and detectives. As the author of Gates of Janus sees it we are all beyond one anothers experience, but, hauntingly, not so far beyond.

Most books, particularly in the true crime genre, are simply books about books. This one is an exception. It is mercifully free of footnotes or, should we say, footprints? In his own field of disturbing expertise, the author speaks with great authority and originality.

The third reason for the uniqueness of this study is, for me, the most fascinating. Although I have read a great deal in the areas of true crime and criminal psychology, my own field is philosophy and religious studies. I am impressed by the philosophical and spiritual light it sheds on the dark corners of homicide and its occult dimensions. Its apparent that the author has spent a great deal of time reading and reflecting on the world he once knew prior to years monastically shuttered within a prison cell. The result reaches a rare level of philosophical maturity, a spiritual perspective of existential relativism, questioning vital issues in psychology, philosophy and theology.

The author shrewdly observes that psychiatrists rarely stray into the field of philosophy. Psychology, like every other discipline, has hidden metaphysical assumptions regarding human identity and the nature of reality. The poverty of Western academia in the fields of psychology, philosophy and theology is highlighted by their failure to respond radically and passionately to the idea, the assumption, that life is meaningless. Academic philosophy is a nine-to-five job in which its professionals spend their lives repeating the assumption that life has no ultimate meaning.

Perhaps it requires the aptitude of a highly sensitive and perceptive serial killer to spell out the consequences of this belief. Dostoevsky, whose psychological perceptions are highly valued by the author of this book, observed that without God, everything is permitted.

Since the time of St. Augustine, theologians have addressed the problem of evil with an inherent navet. Its a navet which this book indirectly but mercilessly exposes to the point of mockery and even of pity. In this universe, everything comes in twos, everything. Wherever there is the light of consciousness there is a shadow. There is a dark force in this universe that will have its way.

Western ethical monotheism still speaks touchingly of the eventual advent of the kingdom of God, in which all things shall be well, either in this world or in the bright blue yonder. The writings of Carl Jung were an exception to this monotheism in its recognition of the shadow archetype. Oriental philosophy and religion also share a realism about this worlds polarities. Humans think in categories and divide in thought what remains undivided by nature. Western culture, by and large, is a celebration of the illusion that light may exist without darkness, good without evil and pleasure without pain. This book will have none of it. It leaves the challenge on the table: is there really a great gulf between the instincts of a serial killer and the public at large? Wittgenstein said, Man can regard all the evil within himself as delusion. But is there what Kierkegaard would call a fatal defect in everybody? One hopes that the present study goads the philosopher, psychologist and theologian into talking turkey and addressing the real issues.

The author asks us to look through the lace curtain of the conventional world, to wake up from the ontological sleep and see the world in its terrifying grandeur. Most people live and dream enchanted by the social trance of mediocrity, blind to what the Zen teacher Sokei-an Sasaki called the shining trance.

Imprisoned for years with psychopaths, psychotics and schizoids, the author has seen things the rest of us can scarcely dream of. Here we have human nature in all its fascinating devious guises. As Dostoevsky darkly observed, If the devil doesnt exist, that man has created him, he has surely created him in his own image and likeness. In this book we are in a short time introduced to the extremes of behaviour, the psychospiritual quagmire: The horrors of hell can be experienced within a single day; thats plenty of time (Wittgenstein). We are offered observations from personal acquaintance of the likes of the poisoner Graham Young and the ripper Peter Sutcliffe. All of this is done with verve, wit and arresting imagery in a manuscript studded with literary, philosophical and religious allusions.

Next page