This book is dedicated to my wife Shirley and my boys Harry and Joshua.

Contents

The staff at libraries and museums in Britain and America have proved extremely helpful during the research needed both for this book and the Ph.D. it is based upon. Most notably, Clayton Lewis, Brian Leigh Dunnigan, Cheney Schopieray, Barbara DeWolfe, Meg Hixon, Diana Sykes, Valerie Proehl, Terese Austin, and the rest of the staff of the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan were welcoming, encouraging, and helpful during my study visits, which were the undoubted highlights of my research. Richard Dabb at the National Army Museum, Ben Cunliffe at the Staffordshire Record Office, Sandra Blake at the Northumberland Estates, and the staff at The National Archives at Kew also offered valuable help and support. My thanks also go to Peter Harrington at the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, for permission to reproduce many of the excellent artworks in their collection.

Dr. Keith A. J. McLay and Professor Peter Gaunt were patient and supportive during four years of Ph.D. research. Their advice, experience, and knowledge greatly strengthened my thesis and, therefore, this book. In addition, Professor John W. Shy at the University of Michigan, Professor Gregory J. W. Urwin at Temple, and Professor Jeremy Black at the University of Exeter were generous with their time when discussing my research.

Finally, I owe thanks to Jenny Clark at Bloomsbury and Lucy Doncaster and Mandy Woods for their work in the production of this book.

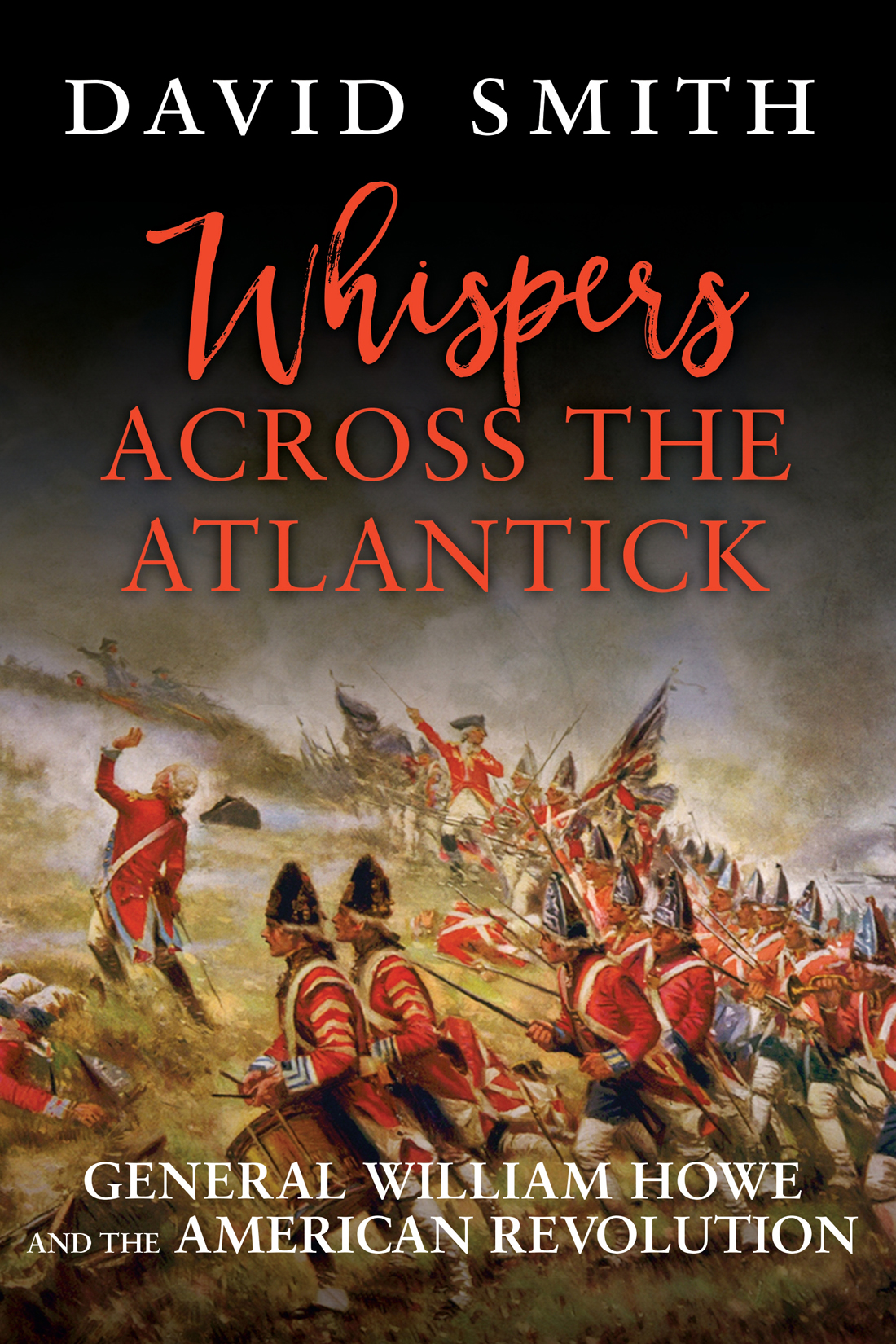

William Howe does not hold a place among the list of revered 18th-century British generals. Following John Churchill and James Wolfe there is a long gap before Arthur Wellesley nips in just before the close of the century, a gap in which Howe resides alongside Henry Clinton, John Burgoyne, and John Carleton. If not entirely forgotten, he has at least been dismissed as a mediocrity; he commanded an army for just two campaigns and is generally considered to have been outgeneraled by George Washington, the American commander-in-chief who was learning his job as he went along. Yet how could he be a mediocrity when he won every battle in which he commanded, never tasting defeat and usually winning with some ease? Such questions make Howe an intriguing figure, but a lack of primary source material has made it difficult to gain a better understanding of this enigmatic general (the Howe family papers are believed to have been destroyed in a fire).

For the bulk of his life, Howe remained in the background. He would sometimes make a fleeting appearance in a letter or report, but rarely took center stage. Like a figure caught in the glare of a flashbulb, Howe can be seen at critical points through his career, but seldom as a moving image. The snapshots are often strikinghe sits at a desk, broken by grief over the death of his oldest brother, he scales a cliff-side path to glory, he demonstrates light infantry tactics to the Kingbut he only becomes a living, breathing, complex man during his period in command in North America and immediately afterward, when a relative abundance of source material is available.

This book is an attempt to understand Howe better. It takes an unapologetically narrow view of the first two campaigns of the War of Independence, mostly considering events through Howes eyes. Where the opinions, perspectives, and comments of others are included, they are generally done so to add to our understanding of Howes decisions or to demonstrate how he so often left everyone around him guessing as to what he was really up to. Howe, an enigma to historians today, was no less so to his contemporaries, friend and foe alike.

A conversation with Professor Shy in 2011 ran along the lines of what does the historian do when the evidence runs out? Perhaps the easiest thing to do is to admit defeat, to own up when no firm and supported conclusions can be drawn. There is little alternative when youre writing a Ph.D., where all statements need to be firmly underpinned with evidence, but my research was helped when it turned out the evidence had not yet quite run out. A draft of Howes famous narrative to the House of Commons, delivered during a parliamentary inquiry into his conduct while commander-in-chief, was sold at auction while I was still working on my Ph.D. and suddenly delivered 85 pages of precious new primary source material. The draft offered telling insights into some of Howes biggest decisions and added subtle detail to the picture of the man. In any case, a book such as this offers a little more leeway than a Ph.D. thesis, and if I have managed to make Howe more of a human being, with all the complexities that come with that, then I will be happy.

April 22, 1779

The man standing in the House of Commons was tall and dark, and had retained the athletic build of his youth. If he seemed nervous, that was understandable. Nothing less than his professional reputation was on the line as he prepared to deliver a speech to the House. In his hands was a thick sheaf of papers and although the majority of the men ready to hear him speak already knew which side they would be on during the coming days, there was still a sense of anticipation. That sheaf of papers might contain answers, and the career of Lieutenant General Sir William Howe had generated plenty of questions.

Howes situation, if not unique, was certainly remarkable. It was more than a year since he had resigned his position as commander-in-chief of the British army in North America and 18 months since he had last led troops in battle against the rebellious colonists. Howe had returned to Britain after winning every major engagement he had fought, after his troops had beaten the rebels at Bunker Hill, Long Island, White Plains, Fort Washington, and the Brandywine. He had returned at his own request and, if not to a heros welcome, at least to a civil one, from the King and the administration of Lord North. He had been rewarded for his efforts with the red ribbon of the Order of the Knights of the Bath.

Yet he now stood before a committee made up of the entire House of Commons, at an inquiry he himself had demanded in an effort to silence the growing whispers from critics who had dogged him almost since he had taken command in America four years previously. For although Howe had won his battles, he had not won his war, and the Americans now seemed close to achieving what at one time had seemed an unthinkable independence from their mother state.

Had Howe been blessed with an awareness of his own limitations he might have entertained doubts over how his speech would be received, because the arena in which he was now engaged was unfamiliar and unsuited to his skills. Physically imposing and a natural leader of men on the battlefield, he was politically naive and a poor speaker off it. There is no evidence that Howe had ever possessed such self-awareness and he was unlikely to suddenly acquire it at the age of 49. How else could he have stood patiently waiting for the House to fall quiet, with only that sheaf of papers to offer them? His speech, the lengthy opening statement in the case to clear his name, was grossly unfit for purpose and some of the sharpest minds (and sharpest tongues) of the day were waiting to hear it. Pathetically ill-equipped to defend his conduct, Sir William nevertheless acted as he had always done and stepped bravely out onto what was to be his last battlefield. He started to speak