PROLOGUE

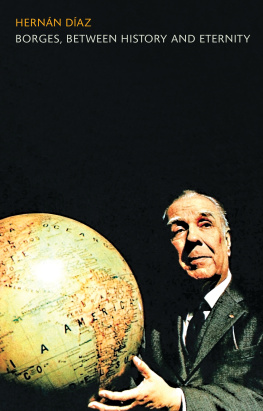

I t was a bright, sunny December day in Buenos Aires, and I was on my way to meet Jorge. My friend Jorge. We were going to have lunch together, as we had on so many other occasions. But this time wasnt like the othersthis time we were meeting to say goodbye.

Id been traveling to Spain on a regular basis for some time and arranging weekend trips for work when my love affair with Granada finally led me to decide to move here, at least for as long as the love affair lasted. And that was the reason why, chatting over Chinese food, we were saying goodbye.

After eating and talking, we had coffee and then... we kept talking. We walked around and had an ice cream. And then talked some more, and walked some more.

Finally, when it got dark, we gave each other a big hug and said, See you soon. I had Lettersfor Claudia, Jorges first book, with me. It was like taking a little piece of him with me, and I still have the dog-eared and much-read copy on the side table in my office today.

Behind us lay the path wed traveled together, as well as the many many hours wed spent working side by side. Time passed (two years, maybe)by which point I had my practice set up in Granadaand one day I wrote to Jorge: it had occurred to me to invite him to come work with me for a weekend. His reply arrived in no time at all: a larger than life, unconditional yes, like Jorge himself. Ever since then, once or twice a year, Doctor Jorge Bucay comes to visit and I have the pleasure of working with him again.

It was over the course of these visits that my patients got to know him, first in person and then through his books. At my request, one day Jorge packed a few copies of Recuentos para Demin (Stories for Demin) in his suitcase. Those few books were devoured by the friends and patients who knew we had them. Everyone who read them lent them to friends, and then they lent them to their friends, and that was when the never-ending question of how and where to get them first cropped up. And that was also when I talked to Jorge about the need to publish them here in Spain.

Thats the story of his presence in Spain, which led to his translation into English and the book you now hold in your hands. Every one of his comments and stories are both helpful and beautiful. One of my favorites is Wings Are For Flying. At one point in this tale, the father says, In order to fly, you have to create enough open space to spread your wings... In order to fly, youve got to start by being willing to take risks.

Jorge knows how to create that space; he accepts responsibility for the risks he takes, and whats more, his wingspan is vast, and awe-inspiring.

Julia Atanaspulo

Granada

COMMON FACTOR

T he first time I went to Jorges office, I knew he wasnt going to be a conventional psychotherapist. Claudia, who had recommended him to me, had warned me that Tubs (El Gordo, as she called him), was a special guy.

At that point, I was sick of conventional therapy in general and, in particular, of being bored for months on end on a psychoanalysts couch. So I called and set up an appointment.

My first impression exceeded all expectations. It was a warm November day (Argentina, remember, is in the southern hemisphere). Id arrived five minutes early and waited in the doorway of his building until exactly my appointment time.

At precisely four thirty I rang the bell. Someone buzzed me in; I pushed the door open and went up to the ninth floor.

I stood waiting in the hallway.

And I waited.

And waited.

And waited!

And when I got tired of waiting, I rang the apartment doorbell.

The door was opened by a man who, at first glance, looked to be dressed for a picnic: jeans, tennis shoes and a loud orange t-shirt.

Hello, he said. His smile, I must confess, was quite comforting.

Hello, I replied. Im Demin.

Yes, I know. What happened? How come it took you so long to come up? Did you get lost?

No, it didnt take me any time at all; I just didnt ring the bell when I got here because I didnt want to be a bother, in case you were with someone.

You didnt want to be a bother? he mimicked, shaking his head with concern. And then he added, as if talking to himself, That must get you far...

I was speechless.

This was the second sentence hed spoken to me, and even though theres no doubt that what he was saying had some truth to it, but, what a son of a bitch!

The space where Jorge saw his patients, which I cant quite bring myself to call an office, was a lot like him: informal, messy, disorganized, warm, colorful, surprising andno sense in pretending otherwisea little dirty. We sat down on two armchairs, facing one another, and as I began talking to him, Jorge sipped mat. Yes, reallyhe was drinking mat during our session.

He offered me some.

Alright, I said.

Alright, what?

Alright to the mat.

I dont understand.

Im accepting; Ill have a mat.

Jorge gave a teasing, servile bow and said, Thank you, Your Majesty, for accepting my mat. But why dont you just tell me whether you actually want one or not, rather than doing me a favor?

This man was going to drive me up the wall.

Yes! I said.

Only at that point was Tubs willing to give me a mate.

I decided to stay a little while longer.

I told him, among many other things, that there had to be something wrong with me, because I had trouble in my interpersonal relationships.

Jorge asked me how I knew that the problem was mine.

I told him that I had problems with my father, with my mother, with my brother, with my partner... and that, thereforeobviouslyI must be the problem. And then, for the first of many times, Jorge told me a story.

Later, in time, I came to learn that Tubs liked fables, parables, stories, aphorisms and well-wrought metaphors. According to him, the only way to truly understand something you havent directly experienced is to have a clear, symbolic picture of it, from the inside.

A fable, anecdote or story, Jorge claimed, will be remembered a hundred times better than any theoretical explanations, psychoanalytic interpretations, or formal approaches.

That day, Jorge told me that, yes, it was possible there might be something not quite right with me, but that my deduction was a dangerous one, because my self-accusatory conclusion wasnt supported by facts that confirmed it. And then he told me one of those stories that he always told in the first person and that it was impossible to know if it was really part of his past, or just fantasy.

My grandfather was something of a lush.

And what he most liked to drink was Turkish anise.

Hed drink anise and add water, to dilute it, but he got drunk on it just the same.

Then hed drink whisky with water, and get drunk on that too.

And hed drink wine with water, and get drunk on that too.

Until one day he decided he had to do something about his drinking.

So he gave up... the water!

THE CHAINED ELEPHANT

I cant do it, I told him. I cant.

Are you sure? he asked.

Yes. Theres nothing Id like more than to be able to sit down with her and tell her how I feel. But I know I cant do it.

Tubs sat down like Buddha, legs folded up on one of those awful blue armchairs in his office. He smiled, looked into my eyes, and, lowering his voice as he did whenever he wanted to be listened to carefully, said:

Let me tell you a story...

And without so much as waiting for me to nod, Jorge launched into it.

When I was little I loved the circus, and what I loved best about the circus were the animals. I was especially enthralled by the elephant, which, as I later learned, was also the other kids favorite animal. During the show, the huge beast flaunted his colossal size, weight and strength. But after his performance, and almost until he came back on stage, one of the elephants legs was always chained to a small post that was staked into the ground.