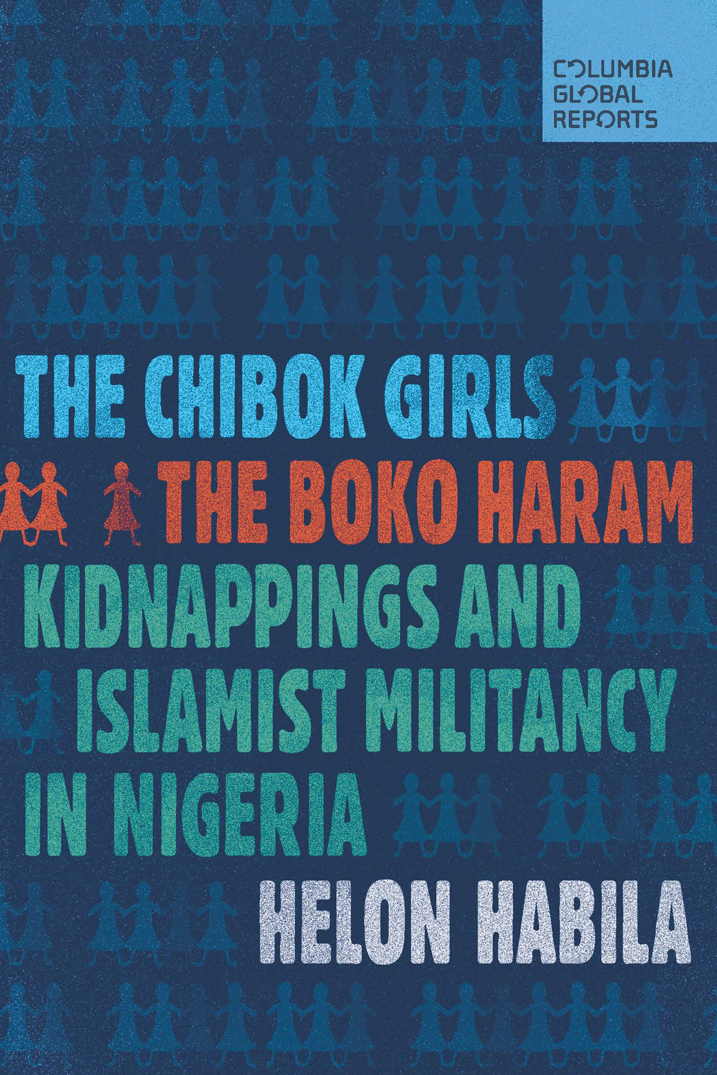

The Chibok Girls:

The Boko Haram Kidnappings and Islamist Militancy in Nigeria

Copyright 2016 by Helon Habila

All rights reserved

Published by Columbia Global Reports

91 Claremont Avenue, Suite 515

New York, NY 10027

globalreports.columbia.edu

facebook.com/columbiaglobalreports

@columbiaGR

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016945881

ISBN: 978-0997126471

Book design by Charlotte Strick and Claire Williams

Map design by Jeffrey L. Ward

Author photograph by Windham-Campbell Prizes

This book is dedicated to the 218 Chibok Girls still missing,

and to all victims of the Boko Haram insurgency.

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

The town lay about a mile ahead, hidden behind rocky hills and baobab trees. There was still one more checkpoint to pass before we entered Chibok. We had left Maiduguri early and spent the night in Yola. The regular route from Maiduguri to Chibok, which passed through Damboa and normally takes two hours, was still in the hands of Boko Haram, and so we had to divert through Damaturu in Yobe State, and then to Gombe in Gombe State, getting to Yola in Adamawa State by nightfalla detour of almost 500 miles.

We left Yola at 10:00 in the morning. This was the coolest it ever gets in these parts, with temperatures falling to the low fifties Fahrenheit at night. It was January, the middle of the season of Harmattan, a wind that blows in from the Sahara, carrying with it dust from the great desert. The fine sand particles go right into your nostrils and eyes, dehydrate the skin, crack the lips, and induce coughing fits and general discomfort. Among the villagers, who mostly go about in slippers or barefoot, the Harmattan cuts deep grooves in their heels. Despite rolling up the windows, the dust still managed to get into the car. All the way from Yola it had clouded the windshield and piled up on the seats and on our clothes and hair.

The closer we got to Chibok, the more checkpoints we encountered. At each stop we had to get out of the car and open the trunk; sometimes the soldiers went through our bags, sometimes they just waved us through. As we passed through Askira-Uba, the last local government area before Chibok, signs of the ongoing battle between Boko Haram and the military became more evident. Burned tanks and military trucks stood at the roadsides, rusting away. There were houses with caved-in roofs and walls pockmarked by bullet holes. There was a destroyed bridge around which we had to detour.

Abbas, my guide, was driving. With us was Michael, a member of the civilian Joint Task Forcelocal hunters and youths working as volunteers alongside the military. He was from Abbass hometown and somehow related to him. We had picked him up on the way, at Lassa junction, where he had waited for us, seated on his bike with only his Dane rifle for company. He had left the bike there and entered the car. When I asked him if the bike was safe there in the bush by itself, he said yes.

Are you sure?

He nodded. He appeared to be a man of few words. I was conscious of him seated right behind me, his rifle pointing in the general direction of my head.

The JTF was a coalition of the different branches of the armed forces formed on an ad-hoc basis to fight the insurgency. Civilian vigilantes knew the terrain better than the soldiers, who were mostly from distant parts of the country and didnt even speak the local languages. Nevertheless the civilian JTFs prowess in fighting Boko Haram had been much exaggerated and mythologizedfor instance, they were believed to possess charms and medicines that made them invulnerable to bullets, and even invisible to the enemy during battle.

Michael was supposed to ease our passage through the checkpoints. And sure enough, after bringing on this new passenger we had passed two checkpoints unharassed; the soldiers only nodded at Michael and waved us throughhis tan uniform and the gun seemed to be doing the trick. Until we reached one where we seemed to have passed a flag without stopping. As we passed a second flag we noticed a soldier under a tree by the roadside shouting and waving at us to stop, his gun pointed at our car.

We thought we were clear to pass...

Another soldier, a superior, came out of a house behind the tree. He was putting on a shirt and his skinny chest was exposed momentarily. You think? You think? he shouted as he joined the others. You people think we are here to play? I dey here for this bush fighting Boko Haram for two years now. Two years I no see my family, and you tell me you think?

Thinking was clearly not allowed. He was almost shaking with anger, shouting at the top of his voice. I was glad he had no gun. You better go and talk to him, I told Michael. There was another car next to ours; a man and the driver stood wordlessly beside the car, listening to the soldiers rants. They were obviously in a similar situation as we were. Michael went to the soldier with the gun and showed his ID card.

So you are civilian JTF? So what? Four months we have been here without salary, our friends are killed by Boko Haram, and I am sick. Four months no pay. And you tell me you think. You will see. I go keep you here for hours in this sun.

He let us go after about 15 minutes.

Checkpoints, or roadblocks as they are also commonly called, are a regular feature of road travel in Nigeria. Nigerians have become resigned to them the way they are resigned to the lack of reliable electricity or running water. Ostensibly, the roadblocks are there for enforcing traffic laws and ensuring travelers safety, but in reality they are nothing but extortion points. They have become a place where you paid your taxes at gunpoint, fully knowing the taxes would not get to the state coffers but into private pockets. Since the Nigerian government placed most of the northeast region of the country under emergency rule in 2013, the roadblocks have proliferated. In some places they have become almost like settlements, humming with beggars, idlers, and boys and girlsout of school due to the insurgencyselling water and food to travelers. In Borno and Yobe states, the epicenter of the Boko Haram insurgency, there were roadblocks at about every two-mile interval. Before the insurgency the blocks were manned by policemen whod chat with you about the weather or about the traffic as you handed them their bribe. Theyd even give you change if you had no small notes; all very civilized. Now the checkpoints were guarded by scowling, uncommunicative soldiers in full war gear. I almost laughed when I saw a sign warning drivers that it is illegal to give bribes at checkpoints, with a phone number to call if a soldier solicited a bribe. This was the face of the new government of Muhammadu Buhari, who was elected in May 2015 on the promise to wipe out corruption and Boko Haram. Abbas told me he had tried the numbers and they didnt work.

At the checkpoints passengers in private cars were sometimes allowed to remain in their vehicle, but passengers in commercial vehicles had to get out and approach the soldiers on foot. Often male passengers had to take off their shirts and raise their hands as they passed the soldiersBoko Haram insurgents sometimes detonated suicide vests at checkpoints. As the passengers passed they presented their ID cards to the soldiers, who compared them to pictures of the 100 most-wanted Boko Haram members prominently displayed at every checkpoint. Abubakar Shekau, the Boko Haram leader, was ranked number 100; his enlarged face with its signature leer occupied the center of the poster. A few faces on the list had already been captured. Recently, Khalid Al-Barnawi, the head of Ansaru (full name: Jamtu Anril Muslimna f Bildis Sdn, or Vanguard for the Protection of Muslims in Black Lands), a Boko Haram splinter group responsible for the kidnapping and killing of many foreigners, had been caught in a hideout in Lokoja, Kogi State. One other reason ID cards were checked was because Boko Haram members never carried them; to them they are a Western invention and therefore haram, or forbidden. I asked Abbas, would anyone without ID be arrested for a Boko Haram member? No, not always. It mostly depended on the discretion of the soldiers, on the answers the defaulter gave; usually the punishment was a fine of anything between 200 naira to 500 naira.