The Unicorns Secret

Murder in the Age of Aquarius

Steven Levy

CONTENTS

Prologue: Of Excellent Reputation

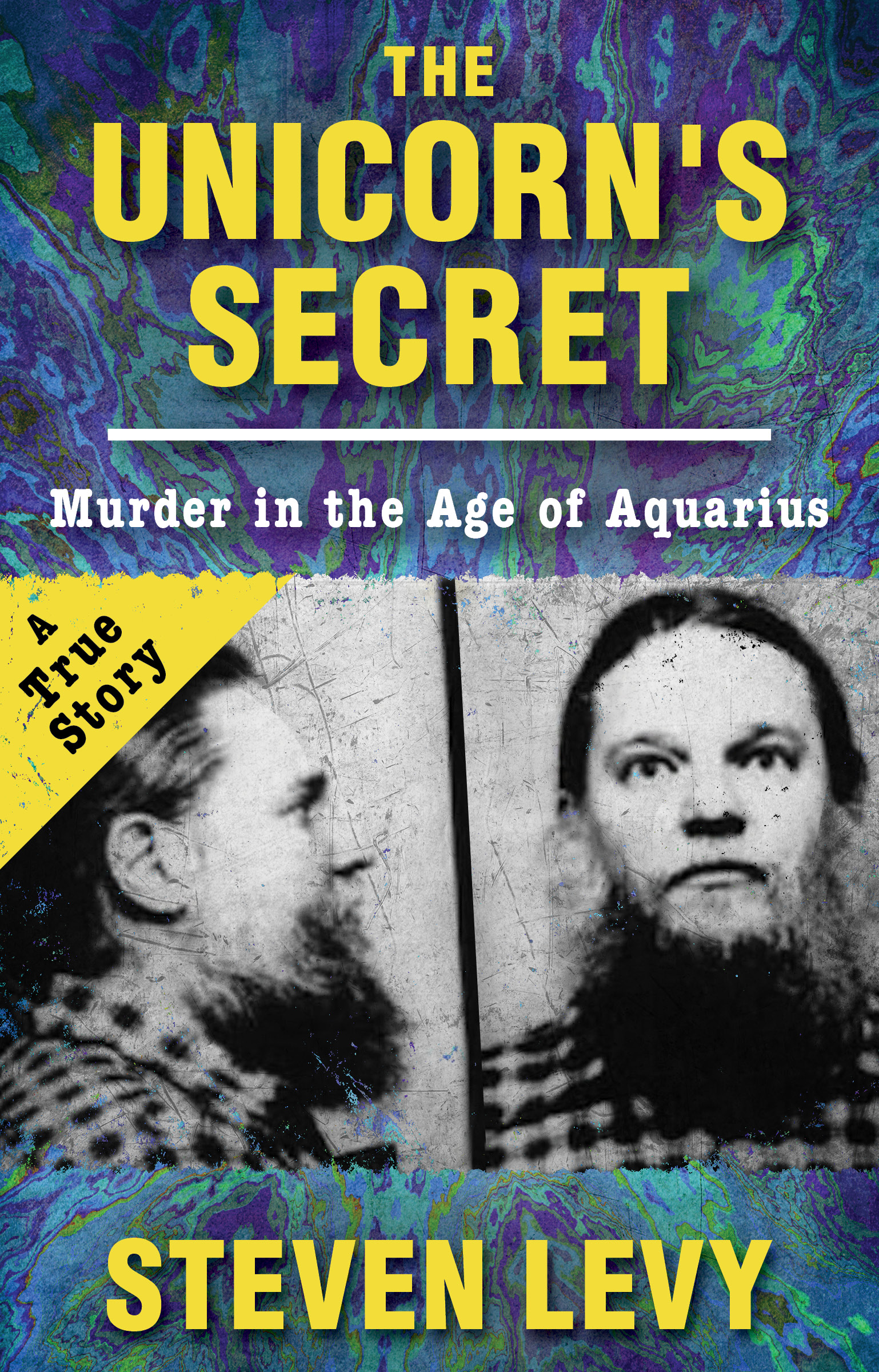

First to take the stand was a corporate attorney. Like the others, he seemed steeped in an air of unreality. He had known the defendant since both were boys. Now, two decades later, he was called on to defend his friend, under oath. He had never dreamed such an endorsement would be required of him, especially in circumstances such as these.

Would you say his character is poor, mediocre, or excellent?

He is of goodexcellentcharacter.

Next to testify was a lecturer at an Ivy League university. He, too, had discounted the charges against Ira Einhorn as not only untrue but impossible.

How would you characterize his reputation?

He has the highest level of integrity. A man who goes out of his way to help people, a man who keeps his word, a man who in his feelings is compassionate and loving.

It was Tuesday, the third of April, 1979, in a Philadelphia courtroom, and Ira Einhorns friends had come to verify his reputation as the benevolent, energizing spirit of his generation. The witnesses were sober, substantial members of the community, described in the newspapers the next day as upper-crust professionals. Prominent as these citizens were, they represented only a tiny fraction of the important people the defendant had come to impress in the course of his unique career. One by one these witnesses made their way to the stand and swore before God to tell the truth. Then the defense lawyer would ask them questions. The lawyer was the citys former district attorney, and within two years he would be sitting in the United States Senate.

Now he addressed a reverend of the Episcopal Church known for his work in the peace movement.

What do you know of Mr. Einhorn with respect to his reliability to keep commitments or dates or obligations of that sort?

I learned to rely on him absolutely. If he said hed do something, hed do it. His reputation is excellent. He is a man of non-violence. Thats the way hes known in the community.

In all his years on the bench, the judge had never seen such an impressive array of volunteers testifying to the character of a defendant. There was a vice-president at Bell Telephone describing Ira Einhorns reputation, again, as excellent. And here was an economist, the former London bureau chief of the Wall Street Journal:

What is his reputation in the community?

The finest, as far as Im aware.

The economist was followed by the dermatology consultant, who was followed by the businessman, who was followed by the playwright, who was followed by the restaurateur, who was followed by the ministera daisy chain of accolades that seemed to have no end. So many prominent people were ready to bestow equally vigorous sworn honorifics that the lawyer had them stand up at their seats and acknowledge that their experiences of the defendant, Ira Einhorn, were congruous with the testimony thus far.

There simply was not enough time for all their praises.

Meanwhile, the man in question seemed to be following the proceedings with steady confidence, bordering on idle amusement. At thirty-eight, he was wide featured and burly, with a checked flannel shirt, a bushy, graying beard, and a ponytail. He was known for his blazing blue eyes, and even today they were not dim. He smiled as his friends shuttled to the stand. You would not think that the crime he was charged with, this man who moved the community to such respectful odes, was premeditated murder. A generous, peace-loving paragon such as the witnesses described would not, as the State charged, kill a thirty-year-old woman whom he loved, and thereafter cold-bloodedly cover up his fatal deed. An act like that would not only be a crime against a fellow human and a crime against the State but a violation of all the righteous values the defendant had come to stand for in the past fifteen years.

But Ira Einhorn was not an ordinary defendant. And this was certainly not an ordinary case.

A CONDITION OF MYSTERY

Less than three weeks before he would be sitting in a courtroom seeking bail as a defendant on a murder charge, the man who called himself the Unicorn flew home to Philadelphia. It was March 15, 1979, the cusp of a new era, and the Unicorn was ready for it. He had spent years embracing the future. A survivor from the sixties, he was a man who had stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the top Yippies when the antiwar protesters levitated the Pentagon in 1967, but only two days earlier he had been rubbing elbows with Prince Chahram Pahlavi-Nia, nephew of the Shah of Iran. They had driven back to London together after the Unicorn addressed an intimate gathering sponsored by the prince. The conference, attended by an elite corps of heavy thinkers, was touted a focal point where environmental, ecological, and spiritual concerns meet internationally. The Unicorns turf.

A month before that, he was in Belgrade, meeting with government officials to help promote relations between America and Yugoslavia, and arranging a centenary celebration for Nikola Tesla, a legendary Yugoslavian inventor.

And just months before that, the Unicorn was at Harvard, lodged in the Establishments belly as a fellow in the Kennedy School of Government.

The whole thing verged on a goof, a cosmic giggle, a sudden hit of irony unleashed by cannabis truth serum. Yet Ira Einhorn, who had adopted the Unicorn nickname in the sixties, was utterly serious. He had gone from a media guru who promoted LSD and organized Be-Ins, to an Establishment-approved self-described planetary enzyme, a New Age pioneer who circulated vital information through the bloodstream of the body politic. Through his networking, consulting, lecturing, and writing, Ira Einhorn was doing his best to inject the values of the sixties into the global mainstream, and amazingly, he was making some headway. Without making compromises in his outlook or life-style, Ira Einhorn and his pro-planetary vision had attracted the attention of some very powerful peopleleading-edge scientists, influential politicians; and captains of industry.

Not bad for a bearded-and-ponytailed former hippie still casual enough to greet callers to his home buck naked. He had plenty to congratulate himself on as he rode home on the TWA Heathrow-Philadelphia flight. He could ponder his burgeoning career or his ballooning list of powerful contacts. Or the future. Instead, he watched the in-flight film, Comes a Horseman, and, being an amateur movie critic, considered it dreadful.

Having drawn his schedule with typical optimism, Ira Einhorn had a speaking engagement the very night he arrived home from England. The flight arrived late, but there was enough time for him to clear customs and return to his West Philadelphia apartment before he had to go crosstown to speak.

Einhorn was a natural choice to address the London Group. The radical psychiatrist who organized the semiregular discussion sessions, Ross Speck, tried to challenge the imagination of the mental health professionals who comprised the group. In the first few sessions, the London Group had entertained healers, drug cultists, and a doctor who treated cancer victims by attempting retribalization based on anthropological work with African tribesthe therapy included chanting and all the primitive trimmings. It was fitting to present Ira Einhorn to the fifteen or so members who would gather in the living room of the Specks South Philadelphia town-house during the middle of March in 1979.