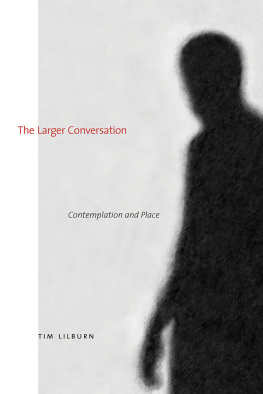

Going Home

Also by the Author

NONFICTION

Living in the World As If It Were Home

Poetry and Knowing (editor)

Thinking and Singing: Poetry and the Practice of Philosophy (editor)

POETRY

Orphic Politics

Desire Never Leaves: The Poetry of Tim Lilburn

(with Alison Calder)

Kill-site

To the River

Moosewood Sandhills

From the Great Above She Opened Her Ear to the Great Below

(with Susan Shantz)

Tourist to Ecstasy

Names of God

Going Home

Tim Lilburn

Copyright 2008 Tim Lilburn

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This edition published in 2008 by

House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto, ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

www.anansi.ca

Distributed in Canada by Distributed in the United States by

HarperCollins Canada Ltd. Publishers Group West

1995 Markham Road 1700 Fourth Street

Scarborough, ON, M1B 5M8 Berkeley, CA 94710

Toll free tel. 1-800-387-0117 Toll free tel. 1-800-788-3123

House of Anansi Press is committed to protecting our natural environment.

As part of our efforts, this book is printed on paper that contains 100% post-consumer recycled fibres, is acid-free, and is processed chlorine-free.

12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

Lilburn, Tim, 1950

Going home / Tim Lilburn.

ISBN 978-0-88784-785-1

1. EcologyPhilosophy. 2. Environmental ethics. 3. North America Environmental

conditions. I. Title.

PS8573.I427Z468 2008 577 C2008-901068-X

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008922789

Cover design: Ingrid Paulson

Cover photograph: Jonathan Kantor/Stone

Text design and typesetting: Ingrid Paulson

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP).

Printed and bound in Canada

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

GEORGE Grant, in his monumental essay In Defence of North America, that rumbling jeremiad beginning Technology and Empire, said descendants of European settlers never would be able to hold the gods of the New World as their own, so never would be autochthonous where they are, no matter how long the history of their stay on the continent might be. This rootlessness was ours, Grant explained, because of what we are and what we did. What we are: detached long ago, while still in Europe, from that part of the Western intellectual tradition that would have taught us the suitability of living undivided from ones earth, we cannot value what we most need, indeed cannot name it. What we did: we met the new land as conquerors and subjugated it. We moved too quickly over the ground, omnivorous, self-uprooting on principle, marked by the inevitably anarchic character of capitalism, to be shaped by where our bodies were. This homelessness of ours has proved disastrous both for human souls and for the colonized land.

Grant believed the ability to be fed by place was lost to North Americans of European descent because of our diminished capacity for the practice of attentiveness. Contemplation ceased to be ours when Reformation Europe severed its links to the thought of Greece and turned to a literally read Bible and to experimental science for sustenance.

...

Going Home attempts a resuscitation of a small part of this jettisoned tradition the erotics of Plato, as they are found in his middle dialogues and his Seventh Letter, which are, as well, the erotics of Christian Platonists of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. It is a book about conversation, a book about reading; it is a book of attempted retrieval; it is, above all, a long walk beside a line of texts Platos Phaedrus and Symposium; John Cassians Conferences; The Divine Names, The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, and The Mystical Theology of pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite; and The Cloud of Unknowing Europes true erotic masterworks, in which a detailed account of desire, desire on the move, is set in place. It also includes a sporadic mulling of works on which the eight books under careful review depend the Odyssey; Origens On First Principles; Evagriuss Praktikos and Chapters on Prayer; the Enneads of Plotinus; Procluss Commentary on the Parmenides; and Richard of St. Victors The Twelve Patriarchs and The Mystical Ark, repositories of the Wests deep, old stories, where an invaluable physics of the heart is stored.

Most of these books are no longer read. They, together with the few that seldom are, form a strand of thought so misrepresented as to be forgotten, a particular way of doing philosophy, a particular way of attending to the world. Eros plays a foundational role in the contemplative philosophy of Plato, who appears near the beginning of this tradition, as it does in the ascetical and mystical theologies of Christian students of Plato; indeed the contemplative life tracked throughout these works amounts to an account of the proper unfolding of desire, as it moves from idiosyncratic, pre-philosophical allegiances to the poverty and inventiveness of contemplative appetite. The incomplete description of desire flowering into contemplation in the dialogues is the substance of Platonic thought, precisely what he took philosophy itself to be. The long reading that follows perhaps will be an occasion of turning, of anagoge, of home-going, for those who take it in. A rejuvenated comprehension of longing, I believe, is the one way home for us.

...

I was born on the prairies but lived in many other places from my late twenties to early forties, mostly in Ontario and the United States, a Jesuit during much of that time, moving every few years from one apostolic assignment to another. I left the order in the late 1980s and worked on farms near Kitchener, Ontario. When I returned to Saskatchewan a few years later, it was late summer. I had been lucky enough to land a job teaching philosophy and literature at a small Catholic college east of Saskatoon, but before I moved on to an acreage Id bought with my then-partner in the area, I spent time in Regina, visiting family and rediscovering the city. Id always had an affection for the Regina Public Library, a trim, modernist building across from Victoria Park downtown; with its tall windows and rows of books, it had been a refuge for me as I grew up. Late one hot afternoon, as I was leaving the library, a thunderstorm was threatening in the southeast, gigantic black clouds bulking over the Saskatchewan Power building. People were filing out of offices, getting into cars or catching buses; some Aboriginal men were gathered in the park.

I suddenly stopped on the steps, struck immobilized by the sense, the sure, sharp realization, that everything around me the looming Power building, Victoria Park and its cenotaph, the beautiful First Baptist Church were not here but seemed slightly dislodged and hovering, leaning elsewhere, their loyalties elsewhere, caught in a momentum of nostalgia for, obeisance to, distant centres of settler power, Winnipeg minimally, but more truly Toronto and the east, New York, London, the Europe to which the older buildings earnestly paid homage. The Aboriginal men, still moving and talking in the park, certainly were autochthonic; they rose effortlessly from the ground. But I did not, nor did the culture I came from, and I felt keenly this deprival.

Next page