Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Jacob Laxen

All rights reserved

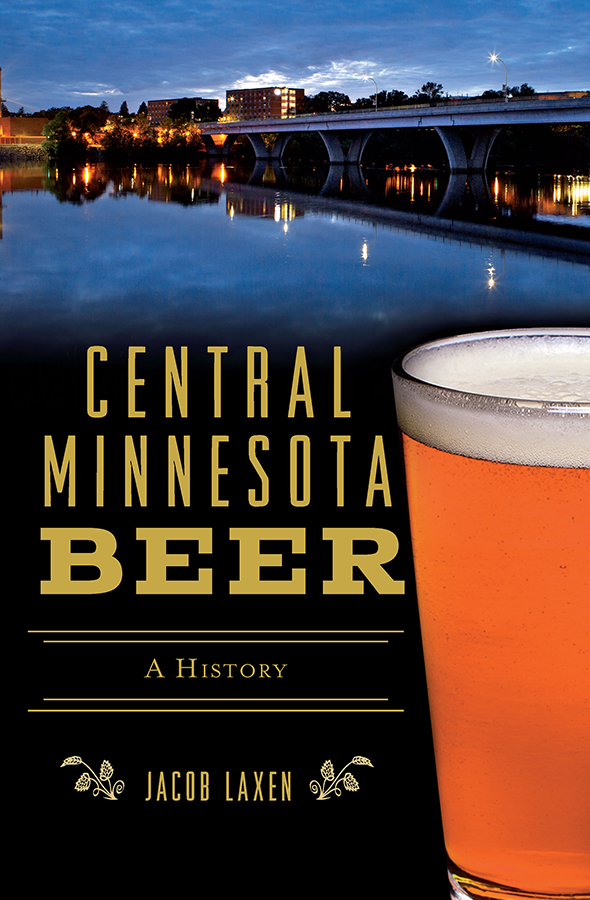

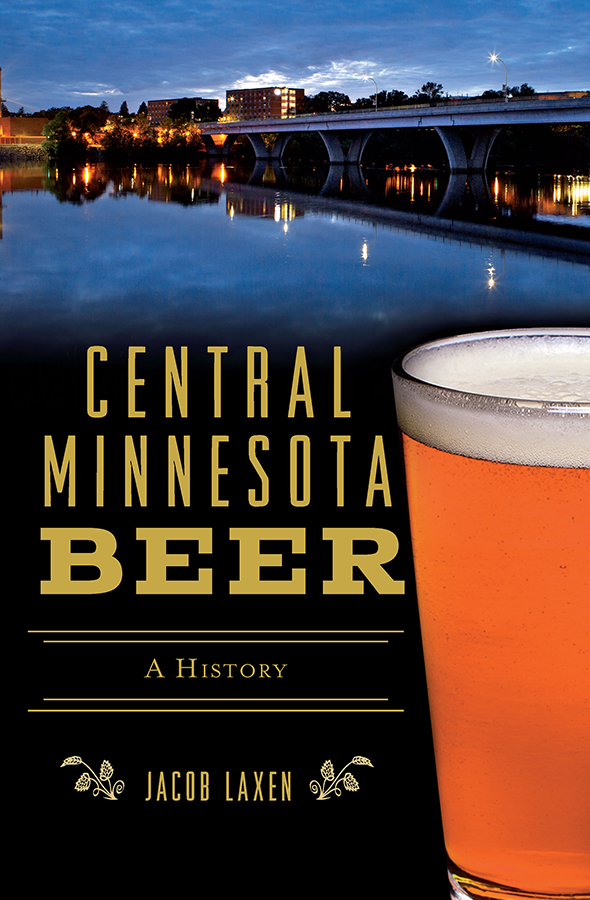

Front cover: An evening look at University Bridge in St. Cloud, Minnesota. The bridge, which is located over the Mississippi River, connects St. Cloud and passes the edge of St. Cloud State University. Photograph by Central Minnesota freelance photographer Kimm Anderson.

First published 2020

e-book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.43966.990.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020930363

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.223.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

As a St. Cloud Times reporter, I covered the reemergence of beer in Central Minnesota. I celebrated many of the breweries grand openings and new beer releases. I was present when liquor stores massively expanded their beer selections and bars doubled their number of tap handles. Options expanded for beer geeks, and it caused me to study the history of brewing in the same communities that I had previously covered.

To many like myself, Central Minnesota is a region where Minnesotans receive college educations. My alma mater, St. Cloud State University, is the states second-largest college behind the University of Minnesota. The nearby town of St. Joseph attracts thousands to St. Johns University and the College of St. Benedicts. St. Cloud Technical and Community College also has a large annual enrollment. For many other Minnesotans, Central Minnesota is a cabin and camping destination, with a number of the large lakesthis is true in my case as well. I grew up in the Twin Cities suburb of Shakopee, which houses the countrys largest beer malt distributor, but I spent nearly every summer weekend of my childhood in our RV at El Rancho Manana Campground near Cold Spring. I remember passing near the Cold Spring Brewery on the way, having no idea just how much history it had. Other members of my family have long lived in the Central Minnesota area.

I worked for two stints at the St. Cloud Times. First, I was a sports reporter for several years while I was attending St. Cloud State University; I was hired by the newspapers longest-tenured sports editor, Dave DeLand. This experience gave me a deeper understanding of St. Cloud as well as the cultures and traditions of the surrounding communities. I was not drinking very good beer at this time. My second stint, however, came during the countrys craft beer revolution of the 2010s. I began exploring different beers with my drinking buddies and contributors to this bookprofessor and photographer Andrew Webster and archivist Adam Shmitty Smith. I covered a number of topics during this stint, including Central Minnesotas food and beverage scene. I was even briefly advertised on a billboard off Division Street. I learned a lot from the columns of Bruce LeBlanc, a local homebrew pioneer who wrote a guest chapter for this book.

My beer coverage in St. Cloud extended beyond Central Minnesota. St. Cloud Timess parent company, USA Today, published my profiles on Sam Adams founder Jim Koch; the American IPA pioneers at Russian River Brewing; the Fat Tire and sour pioneers from New Belgium; and the founders of the storied Alaskan Brewing. They also published my behind-the-scenes look at how Ballast Point became the first craft brewery that was sold for $1 billion and my articles about Budweisers nationwide shopping spree of craft breweries and controversial Super Bowl commercials dissing craft beer and pumpkin peach ales. I even got to interview former professional wrestler Stone Cold Steve Austin and NBA star Chris Bosh about their passions for beer in the old St. Cloud Times office. Craft beer samples made across the country began showing up in my mailboxes at my office and home. I even received a bottle of the super rare Sam Adams Utopiawhich I proceeded to drop and shatter, only getting a few sips off of the bottles glass shards.

I eventually transferred to the beer hub of Fort Collins, Colorado, where I continue to cover the beer scene closely. The area oddly had a large impact on Central Minnesotas beer revival. Fort Collins houses a major Budweiser brewery, New Belgium Brewing, Odell Brewing, Funkwerks and a number of other breweriesit is a beer heaven. But I have never forgotten Central Minnesota and its beer history. Beer has been an integral part of politics, business and culture in the region for more than a century. The goal of this book is to tell the tale of Central Minnesota brewing and how it continues to flourish with bountiful water sources today.

INTRODUCTION

In the center of the Land of Ten Thousand Lakes rests a bounty of water. The Mississippi River cuts through the heart of Central Minnesota, picking up steam from its humble beginnings in the shallow Lake Itasca, where it starts its 2,348-mile journey downstream to the Gulf of Mexico. Central Minnesota also has sparkling springs that are fed by glacial lakes, flowing tributary rivers and giant lakes the size of Paul Bunyans footprint.

For generations, various Native American tribes collected resources in and around Central Minnesotas waterways. Later, explorers journaled their amazement and wonder at the areas various waterways; European settlers followed in the mid-1800s. The bountiful waterways were the perfect sources for brewing beer. A large influx of German settlers brought the German culture of brewing to the area. Swiss and Hungarian immigrants also had a significant impact on early Central Minnesota brewing. The settlers were accustomed to Europes industrial culture, where drinking beer was safer than drinking the bacteria-filled water that was available at the timethe heating process of brewing kills off bacteria and parasites in water. By the turn of the twentieth century, beer was advertised in Central Minnesota newspapers as a medicine to aid digestion and as a healthy substitute for coffee. Historians say people of all ages drank prior to Prohibition.

Fires burned down many of Central Minnesotas earliest breweries. Some empires were ruined by Prohibition, and others fizzled out shortly after the nationwide ban on alcohol, when significantly stricter laws and regulations were placed on the industry. But through thick and thin, one Central Minnesota brewery endured. Today, the Cold Spring Brewing Company operates in the same spot as it did when Michael Sargl first brewed there with a kettle in 1874now under the Third Street Brewhouse label.

Brewpubs brought a new beer culture to Central Minnesota in the mid-1990s, and one St. Cloud brewery spread the Granite Citys culture and its beers across the country. A new beer culture took hold in Minnesota, thanks to a piece of 2011 state legislation known as the Surly Bill, named after the popular Twin Cities brewery that legally challenged the existing laws. The restrictive laws that had once forced the number of Minnesota breweries to dwindle down to just four were overturned, and Minnesotas breweries were revived to number more than one hundred. The North Star State has been nationally revered for its growing beer community, regularly claiming medals at the annual Great American Beer Festival. Central Minnesota is once again using its bountiful waterways to make beer. Breweries have popped up across the region, giving townsboth large and smalltaprooms that operate with a much more relaxed vibe than a traditional bar.

Next page