Acknowledgments go to: Bob Brewer, whose use of his personal library and supportive friendship eased the task; Carrie Getty, whom I cannot thank enough for everything over the years; Daniel Bradford, for his support; Dave Heidrich, whose words, Hey its only beer, were constantly good reminders; and finally, Lisa Variano, for her contributions on the working text.

T HE D AWN OF A MERICAN B EER

Swinging gently on its anchor line, the ship was nearly silent in the predawn light. The low groaning of the rigging and the soft lapping of waves against the hull were the only sounds. Taking it in was a solitary figure, silhouetted in the light of an oil lamp. The shoreline, becoming more visible as the minutes passed, offered a strange combination of hope and fear.

The first one awake, the expeditions leader had finished breakfast before coming on deck, bringing with him only what remained of his morning drink. It was the drink that had him concerned, for on drawing his morning beer he had seen how perilously low the ships supply of ale had dwindled.

At first light the small boats would be loaded and begin the process of shuttling the newcomers and landing their provisions. There was no thought of any delay, they needed to get ashore and begin brewing their own beer. On the previous evening, when the ship had arrived in the small harbor, the company of immigrants agreed on the priorities for construction of community buildings; a brewery was near the top of the list. The leader hoped the brewery would be functional before the meager supply they brought with them ran out. After all, beer was a necessity.

This scene was repeated many times from the late 1500s to the early 1700s in colonial North America. Small wooden ships crisscrossed the Atlantic, ferrying newcomers to an unspoiled land. They all had different reasons for making the trip. Some came for freedom of religion, speech, or philosophical beliefs. Others making the difficult passage were driven by political motives, and still more came for economic opportunities. A number were fleeing families, and a few were fleeing the law. Their reasons for leaving the relative security of Europe for an unknown land were certainly diverse, but most of them had one thing in common: they drank beer.

To comprehend the cultural importance of beer requires an understanding of its role in civilization. Beer and society have been inseparable companions for thousands of years. Literally, the two have gone hand in hand. When people first settled together they were motivated to do so by a common cause: the thirst for beer. All the thoughts, feelings, and beliefs the colonists brought with them to North America were the result of societys millennia-old marriage with beer. Indeed, drawing a fresh mug of ale was, at that time, as indispensable as drawing a breath.

More than a mere cultural habit, beer drinking evolved into a healthful practice. Brewers have to boil water to make beer, thus killing the microbes that imperil health. In Europe, fouled drinking water placed city dwellers in peril; those who used the fetid supply regularly developed serious health problems. In England, Parliament tried to enact laws against pollution, but it was too late to prevent widespread disease. Nearly every supply was horribly tainted.

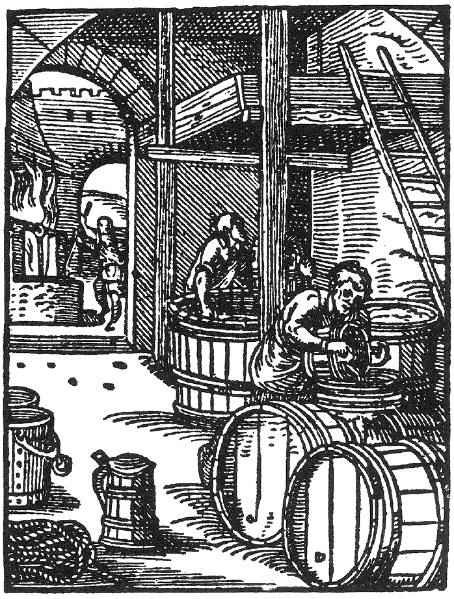

An ancient brew house.

True enough, the pristine streams running through the virgin forests of the new land were pure and clean, but still, the settlers simply wouldnt drink the water, because they brought with them frightening memories of their homelands deteriorating water supplies. There, rivers and streams were becoming the equivalents of flowing dumps.

By the mid-1400s the bias against drinking water in Europe was deeply ingrained. Sir John Fortescue wrote of the English peasants: They drink no water unless it be... for devotion.

Settlers in the Americas lost sight of the fact that European beer drinking, and avoidance of water, was driven by fear of pollution; they simply didnt trust it. No amount of reasoning about the safe supply running in the rivers of the New World could make them drink it. Luckily they knew of a safe alternative: beer.

For settlers, one of the most precious cargoes their tiny ships held was beer. It was more than a comforting reminder of the

Beer Arrives in North America: The Start of a Journey to Greatness

B UILDING A H OME AND A B REWERY, T OO

The Early 1600s

A t first light the settlers left the safe confines of the ships quarters and began assembling on deck. Sky and sea slowly brightened, the heavy woods along the shore formed a dark barrier. Looking toward shore, the settlers were filled with confused emotions that ran the gamut from apprehension to excitement, fear to joy. Only a short boat ride away their new home beckoned them, and though it promised hope and opportunity, it was totally devoid of both essentials and comfortsespecially beer.

It had been a long journey. Too much of it was spent confined in cramped, dark quarters below deck. Sickness was common, food was poor at best, privacy was nonexistent, and the accommodations offered scant physical comfort. Despite all the unknowns ashore, they were eager to leave the ship.