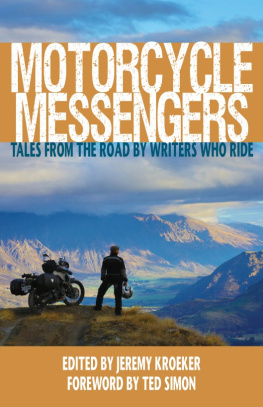

Motorcycle Messengers

tales from the road by writers who ride

Edited by Jeremy Kroeker

Foreword by Ted Simon

Copyright 2015 by Oscillator Press. Allrights reserved.

All stories, articles, and excerpts arecopyright of their creators, and are reproduced here withpermission.

Smashwords Edition

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personalenjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away toother people. If you would like to share this book with anotherperson, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. Ifyoure reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was notpurchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.comand purchase your own copy.

In summary, just buy stuff instead of rippingit off. It really helps actual people.

OscillatorPress.com

Tableof Contents

Books by Jeremy Kroeker

Motorcycle Therapy

Through Dust and Darkness

For Nevil Stow,

inventor of the garagarita

(part beverage, part experience).

By Ted Simon

I couldnt be more enthusiastic about a collection ofstories by bikers. After all, the foundation that bears my name isdedicated to encouraging exactly this kind of thingand yet Irecognize that for many readers, there is something odd about theexpectation that motorcyclists would produce literature. That wasthe main reason why Pirsigs book Zen and the Art of MotorcycleMaintenance created such a sensation. The juxtaposition ofbikes and philosophy was bizarre enough to titillate ordinaryreaders (by ordinary, I naturally mean non-riders) who wouldnormally never touch a bike with a dipstick. Fortunately, the bookwas good enough to sustain their interest. Of course it wasmoremuch moreabout philosophy than biking, just as my own booksare much more about travel than motorcycles. Indeed, most of thestories in this collection have more to do with the world aroundthe rider than the machine he rides. So what is the justificationfor putting them all together in one volume?

Its not just a gimmick.

I maintain that people who use a motorcycle to travelhave a sharper, truer view of everything around them. Its anecessity for survival. The need to be always alert, always readyto deal with some unexpected contingency, greatly enhances theperception or, as Dr. Johnson put it in a different context, itconcentrates the mind wonderfully. What would be an inconvenientand expensive accident in a car can be fatal on a bike. Preciselybecause they are so vulnerable and dependent on their environment,riders are better equipped to cross over cultural divides.

Unlike their four-wheeled brethren who are protectedand separated from the world in their steel cages, motorcyclistsare visible human beings and, especially in remote areas wheremotorcycles are not so common, they engender curiosity andsympathy. Wise riders take advantage of this; they travel slowly,stop to ask for directions, to talk, to drink a cup of tea, to findout whats going on, and accept invitations. Generally, they have amuch broader experience of the warmth and generosity that still,thank heavens, persist among people of all kinds everywhere. Thisis the message they carry with them, from host to host, fromcountry to country, and eventually back home. There is abundantevidence of that in these stories.

Ted Simon

California, U.S.A.

2015

The following is an excerpt from the book Red Tapeand White Knuckles, published in the U.K. by Penguin RandomHouse, and in the U.S.A. by Octane Press (OctanePress.com). Usedwith permission.

By Lois Pryce

The usual hoo-hah involving small men with big rubberstamps was particularly drawn-out and painful, requiring a constantstream of cash and an industrial scale of photocopying. By the endof it even Ricky, my self-appointed helper, was starting to look abit stressed, and we lost his friend Kevin somewhere along the waywhen he got roughed up and thrown out of an office by an angry hulkof a man in a grey uniform. Eventually Ricky beckoned me to followhim aboard the ferry, and I rode up the rickety gangplank, clankingmy way onto the boat. It was a rusting old iron heap that comprisedno more than a covered deck and a few rows of seats for passengers.I parked my bike facing out towards Kinshasa and stared over thewater, feeling more apprehensive than ever before on myjourney.

There were plenty of men and women coming aboard,carrying enormous sacks of grain on their heads, several men whowere already drunk at nine in the morning, and a surprisingly largenumber of cripples dragging themselves around on their witheredlimbs, or being pushed aboard in homemade Heath Robinson-stylewheelchairs. I asked Ricky why there were so many of them, and hesneered distastefully.

They are trouble, big trouble. They can travel cheapon the ferry, so they go back and forth, selling and buying betweenBrazzaville and Kinshasa; they sell cheaper than everyone else, andthey smuggle things too. They are trouble, very aggressive whenthey are all together like that. You must not talk to them.

I watched them arranging themselves and their strangecollection of wheelchairs and tricycles piled up with goods. Africais probably the worst place in the world to be disabled, but theywere getting on with it, survivors making something of theirpitiful lives. But they all had the look that I now knew so well:the cold, empty eyes of the Congo.

A few able-bodied chancers were diving off the wharfinto the brown swirling water and swimming round to the other sideof the boat, where they clambered aboard to avoid paying for aticket. One of them was even carrying a sack of rice while hecarried out this manoeuvre, holding it on his head and swimmingwith his free arm.

A burst of shouting and banging drew my attentionaway to the top of the gangplank, where an elderly woman and one ofthe deckhands were in the midst of a fistfight. She punched him inthe chest, then he shoved her up against a bulkhead. Her skull madea dull clanking sound as it came into contact with the rusty ironwall; fortunately she was wearing a large and elaborate headdress,which hopefully softened the blow. Not to be deterred, she cameback at him with a right hook in the face, which he returnedimmediately. It was the Rumble in the Jungle for the twenty-firstcentury: Ali and Foreman had nothing on these two as they continuedto batter each other, sometimes rolling on the floor, but alwayscoming up for more. It was turning into quite a commotion as morepassengers boarded the ferry, pushing their way past the scrappingcouple. In the end some of the heftier-looking males on board,including Ricky, steamed in and successfully pulled them apart.

What was all that about? I asked Ricky when theexcitement had died down. The elderly woman was sitting alone,perched on a sack of rice, her face clouded with fury.

Oh, nothing. She is his mother; they are alwaysfighting, he explained with a shrug.

Ricky bid me farewell. He had other business toattend to, more scams and fixes to take care of, and, no doubt,more fights to break up.

Good luck in Kinshasa, he said, shaking hishead.

Now that Ricky had gone and the drama of the fighthad subsided, attention was turned towards me and I was soonsurrounded by a curious crowd. They formed a circle around me andthe bike and stood there staring, except for one particular man whowas steaming drunk and insisted on lurching towards me and drapinghis arm round my shoulders. Each time he did this I would hop roundthe other side of the bike, but he always followed, staggering andslurring after me, sending me skipping off back to the other side,until I was trotting non-stop around the bike with him in hotpursuit. It was straight out of The Benny Hill Show; theonly thing missing was a novelty theme tune. This ridiculouscarry-on continued for some time until one of the young men in thecrowd hauled him away with a few choice words and a look ofdisgust. Drunks, the disabled, old women; there was no respect forthese weak, lowly members of society in the Congo. It was survivalof the fittest, quite literally the law of the jungle.