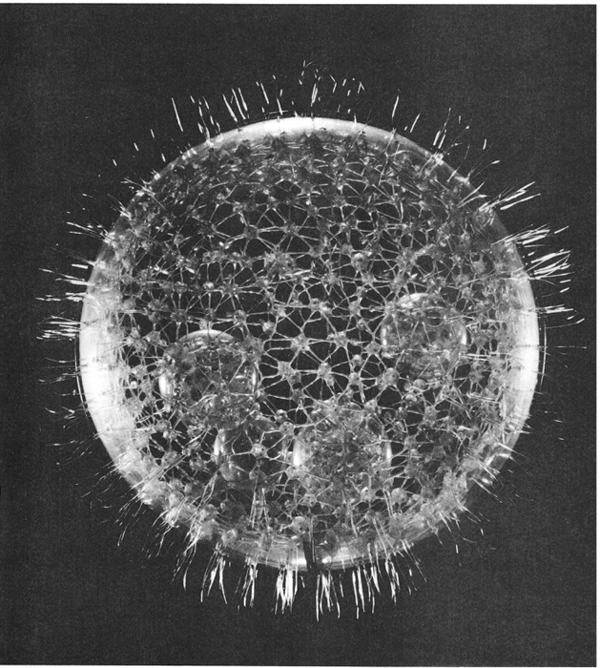

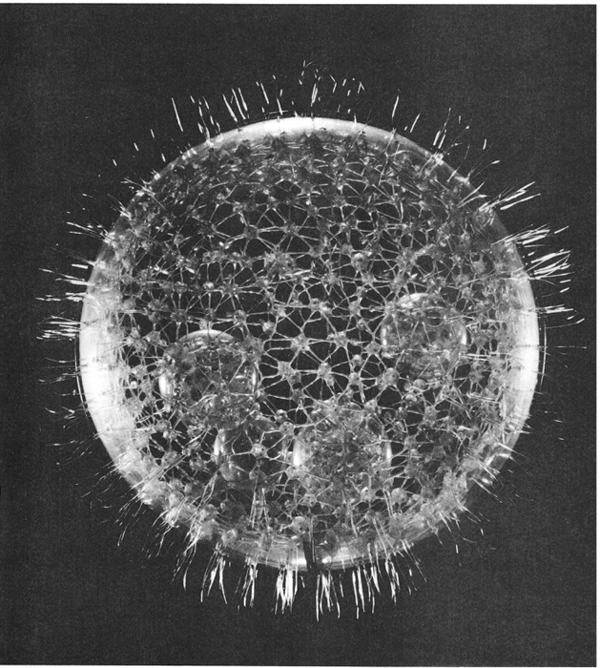

Glass model of Protozoa (Flagellata). Courtesy American Museum of Natural History.

A

World

in a

Drop of Water

Exploring with a Microscope

Alvin and Virginia Silverstein

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Copyright

Copyright 1969 by Alvin and Virginia Silverstein

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 1998 is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Atheneum, New York in 1969.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Silverstein, Alvin.

A world in a drop of water : exploring with a microscope / Alvin and Virginia Silverstein.

p. cm.

Originally published: 1st ed. New York : Atheneum, 1969.

Includes index.

Summary: Describes the structure and characteristics of the amoeba, Paramecium, and other members of the circus that Leeuwenhoek discovered in a drop of water.

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-40381-6 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-486-40381-5 (pbk.)

1. Freshwater biologyJuvenile literature. [1. Freshwater biology.] I. Silverstein, Virginia B. II. Title.

QH96.16.S55 1998 98-27926

578.76dc21 CIP

AC

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

40381508

www.doverpublications.com

Contents

A

World

in a

Drop of Water

Lets Go Hunting

LETS GO OUT HUNTING! What shall we hunt for? Lions and tigers? Of course not! We wouldnt be able to find any real lions and tigers nearby (except in the zoo). We could hunt butterflies or grasshoppers or frogs. But lets try something more exciting this time. Lets go after some stranger game.

How about a creature that can squeeze in and out like an accordion and has two whirling wheels on top of its head? And another that looks like a blob of jelly, which can change its shape and send out snakelike arms to catch its prey? How about a green-speckled creature that darts about with a lashing, whiplike tail?

Do they sound as if they came from another world? Where can we find them? How can we catch them? Will it be dangerous?

They live closer than you think. And the strange monsters that we seek will not hurt you at all, no matter how fierce they look.

For our hunting expedition, no special equipment will be needed at first. Just bring along a few jars. Ordinary glass jars will do.

We are going to a nearby pond. For the strange big game that we are hunting is not really big at all. In fact, our monsters are to be found in every pond, large and small. If we know how to look for them, we can find them, swimming and floating and creeping in any pond.

At the pond we find that a velvet green moss makes a soft mat along the edge. Tall grassy weeds grow up through the quiet water. The top of the water is covered with a thin coat of green. Suddenly there is a big splash. A frog that was sunning itself on a rock must have heard us coming. As the ripples die away, we can see through the hole that he tore in the thin green coverlet.

Green frog. Courtesy American Museum of Natural History.

There is a large fish swiftly chasing a group of tiny minnows, which dart away in all directions. Crawling along the shallow bottom and perched on the stalks of the water plants are snails of different sizes. If you look closely, you can also see round little worms, no longer than the end of your finger.

We could spend hours watching these interesting animals and plants. But we are after stranger game. And our game is far smaller. The creatures that we seek are so small that we cannot even see them. When we get home, we will need a microscope to watch them.

To capture the creatures, take one of your jars and skim some water from the top of the pond. Now take another jar and scoop out some water and mud from the bottom of the pond. This is all that needs to be done. Now lets see what we have caught.

A Circus Full of Life

WE ARE ABOUT TO PEEK into a very different worlda world that was discovered about three hundred years ago. In those days microscopes were new, and they were not very good. But a Dutchman named Antony van Leeuwenhoek learned how to polish lenses and put them in frames to make small hand microscopes. As time passed, he became more and more interested in his hobby. He would spend days and even weeks, polishing away on one tiny lens until he had it perfect. Then he would slip it into one of his small brass frames and examine all sorts of things with it.

Leeuwenhoek grew more and more excited at the things he saw. Through his tiny lenses, some no bigger than the head of a pin, he saw things smaller than anyone had ever seen before. He looked at little fleas and saw even smaller creatures crawling on their backs. He watched the blood flowing in fine blood vessels in a tadpoles tail. He spent many hours studying hair and skin and even scrapings from his own teeth.

Drawing of Leeuwenhoek using his microscope. Eric Fraser.

But Leeuwenhoeks greatest surprise came one day when he looked through one of his wondrous lenses at a drop of rain water that had stood for a few days in a pot in his garden. Here he discovered a new world. In a single drop of water, he saw a circus full of life.

He saw clear little globs, which poked out little horns as they moved along. He peered at slipper-shaped creatures gliding through the water, swimming along with the help of many tiny feet. He saw some little beasts that zipped by so fast and were so small that he could not tell just what they looked like. Sometimes they would stand still, and sometimes they would spin about like a top.

Leeuwenhoek learned that he could grow these small creatures in pepper water. They grew so well that he was able to see many thousands of these animalcules or little animals in a single drop of pepper water.

For nearly fifty years this Dutchman gazed through his many microscopes at his busy little worlds. He was so excited that he told everyone about his discoveries. He told his friends. He told the shopkeepers of the town. He told the officials at the town hall. And everyone came to his house to look through his microscopes. But most important of all, he wrote letters to a famous group of scientists, members of the Royal Society of London, telling them of the small creatures he had seen.

These scientists were so amazed that at first they did not believe him. But after a time they saw this tiny world for themselves and recognized Leeuwenhoek as a fine scientist.

Now we are about to explore the world that Leeuwenhoek discovered nearly three hundred years ago.

The Amoeba:

a Living Glob

TO SEE WHAT KINDS of small creatures live in a pond, we too must look at a drop of water under a microscope. First well try the water that we scooped up from the bottom of the pond. The mud and leaves have settled, and the water is now clear. One drop of the clear water goes under the lens, and we find that it is swarming with life. Tiny creatures of different sizes and shapes are busily swimming to and fro. Little balls and rods and hooks wiggle and dart about.

Next page