Copyright 2007 by Frank Pope

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Pope, Frank.

Dragon Sea: a true tale of treasure, archeology,

and greed off the coast of Vietnam/Frank Pope.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

1. VietnamAntiquities. 2. Pottery, Vietnamese. 3. Underwater archaeologyVietnamHoi An. 4. Treasure trovesVietnamHoi An. I. Title.

DS556.4.P67 2007

910.9164'72dc22 2006036324

ISBN 978-0-15-101207-7

ISBN 978-0-15-603329-9 (pbk.)

e ISBN 978-0-547-53896-9

v1.0814

To my mother and father, for their gift of freedom.

FOREWORD

Just as the moon lures the tides, the ocean tugs at a mans mind. Her waters can be many things at once: A healer and a killer, a canvas for contemplation, and an unforgiving workplace. For me, as for so many other young men through the ages, they offered an escape. Fresh out of school with a privileged but conventional education, I wanted to avoid the drudgery that seemed to loom ahead, and to go where there were no trodden paths.

The ocean covers 70 percent of the earths surface, yet even in its most explored region, Californias Monterey Bay, human eyes have seen barely 1 percent of its floor. Given such an unmapped frontier, there were many directions I could have taken and many disciplines to which I could have devoted myself. Geologists follow the undersea forces that drive our drifting continents. Meteorologists watch the sea lead the worlds weather in a dance of magical complexity. An imperceptible rise in its temperature sends wind whirling into a devastating hurricane, while an unseen shift of a remote ocean current plunges a continent into winter. Biochemists find life in the depths that survives without light and organisms built without carbon. Marine zoologists explore an environment more exotic than any rain forest: Bring up an animal from below ten thousand feet (still shallower than the oceans average depth), and the odds are even that youll have brought up a completely unknown species.

By chance I was drawn into studying maritime archeology, which seeks to understand the story of mankinds four-thousand-year-old affair with the sea. Chance, that is, and the peculiarly powerful allure of shipwrecks. Perhaps the contrast of encountering something man-made in so inhuman an element put my senses on alert, but when I saw my first shipwreck, lying at the bottom of a Greek island harbor, it sparked a fascination that wouldnt die. That sunken ship carried a message from the past that had been sealed on the day of its sinking, the result of a storm, a battle, or a tragic mistakeI didnt know which. It conjured up an era of exploration, trade, and adventure now long passed.

Mensun Bound, director of Oxford Universitys Maritime Archaeological Research and Excavation unit (MARE), was leading the survey of the medieval wreck, which had sunk off Zakynthos Island. I was an eighteen-year-old volunteer. My father, a classical scholar with a special interest in the history of decipherment, had helped sponsor Mensuns first excavation and so, a few years down the line, Mensun agreed to take me on as a dogsbody. He sensed my enthusiasm and fanned the flame. Over the years that followed he became both a mentor and a friend as we worked together on shipwrecks in Uruguay, Italy, Greece, Mozambique, and the Cape Verde Islands.

I began my journey in archeology expecting to find a clear division between good and bad, right and wrong; instead, I found that the line shifted like bars of barometric pressure on a weather chart. This book tells the story of my last expedition with Mensun, which took place in the South China Sea. The trip was different from all the others on which I had gone, for on it I learned that beyond the power to terrify, enrich, and make judgment, the ocean could also lay bare the very nature of man.

PROLOGUE

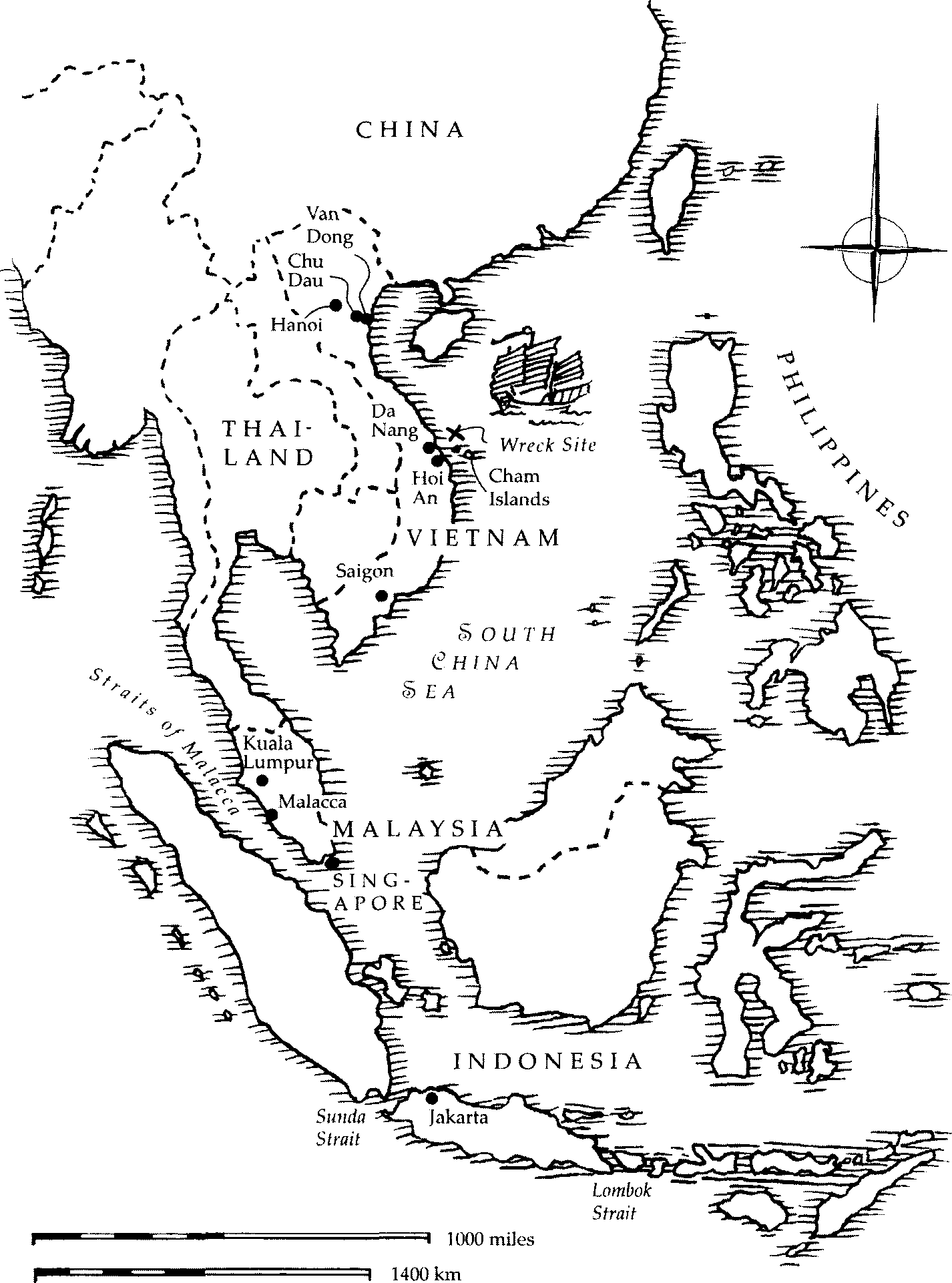

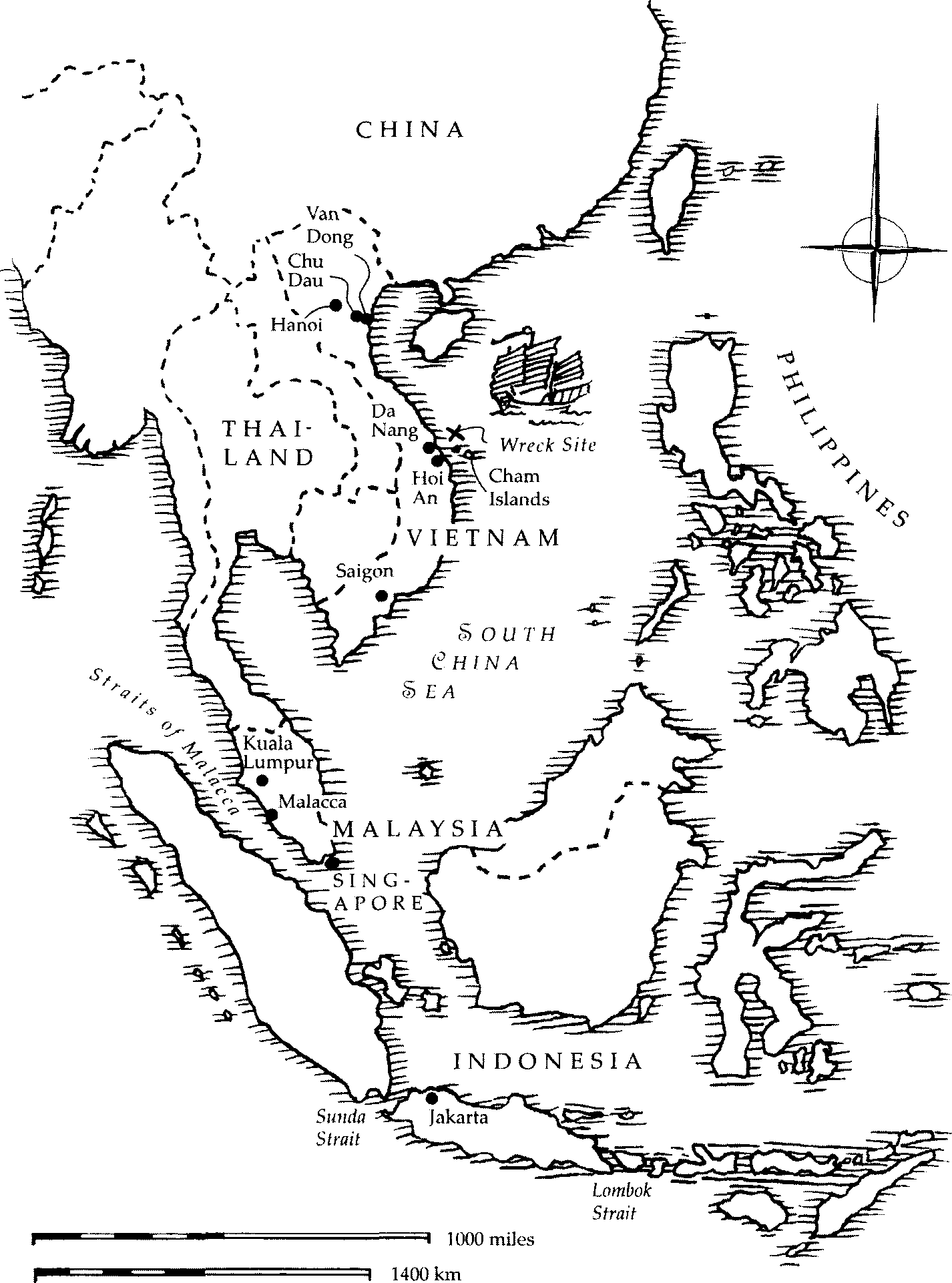

South China Sea, Mid-fifteenth Century

Every day they waited the voyage ahead became more dangerous. South China Seas typhoon season was approaching and the captain was growing increasingly anxious, but the owner refused to leave Van Dong before the ships holds were full of pottery. Only when the crew saw the land receding behind them did they at last begin to relax, even though the hull that bore them was riding low in the water.

Five days into the journey the wind died completely. The sailors knew trouble was coming, warned by both superstition and experience. When the first waves arrived the ship began a long, lazy roll. With the sea glassy smooth and not one breath of a breeze, the end of each pendulous swing was marked by the clunk of loose pottery in the holds and the clatter of cauldrons hanging in the galley. Then the wind began to blow, howling as it wrestled with the mast and moaning angrily through the stays. At first the crew tried to harness the gale to make up for lost time, but the storm soon forced them to drop the bamboo sails back to the deck.

In the hours that followed the weather only worsened. Then the ships blunt bow shuddered into an oncoming wave and, breaching free from the crest, slipped sideways into a yawning trough. Men on deck who were heaving at the pumps turned and shoutedin terror as a mountain of water loomed over them. With a summit ridged by furious whitewater, the wave scooped the vessel up its near-vertical face and flung it onto its beam ends.

Below in the galley a kitchen girl cowered as a fist of water punched through the window and sluiced over her. She lay dazed on her back, wedged into the valley between wall and floor, waiting.

With agonizing slowness the ship began a slow roll back upright, her heavy holds now burdened with tons of seawater. Then a second rogue wave hit and the ship rolled over again. This time the hull made no attempt to push itself back upright and the sea flooded into the galley, unstoppable and inexhaustible.

Broken masts and sails streamed above the ship as it sank. Soon the girls struggles stopped. Weightless among the cauldrons and the kettles, haloed by her billowing hair, life faded from her eyes as around her the water grew dark with depth.

When the ship finally hit the seabed it too had stopped struggling. Ropes coiled downward through fleeing bubbles as it eased to rest in the mud, the sails settling onto the deck like the folds of an emperors gown.

INTRODUCTION

Grandchildren of the Dragon

O FF THE SOUTHEASTERN FLANK of the Asian continent lies the worlds largest body of water aside from the five oceans themselves: the typhoon-torn South China Sea. The encircling islands and peninsulas of Malaysia and the Philippines, rather than providing shelter from oceanic winds and currents, serve instead to channel and focus them. Late every summer, low-pressure systems form in the Northwest Pacific and wheel toward the East Asian seaboard, intensifying into tropical depressions, storms, and occasionally typhoons that ravage the coastline. More powerful than any other meteorological force on earth, typhoons are the Pacific Oceans version of hurricanes, anti-cyclones that can spin at speeds of up to 120 miles per hour. Caused by predictable conditions, typhoons can be avoided by the mariner so long as he stays out of their territory between mid-May and September. Unlike mariners, however, typhoons are not calendar-watchers. They sometimes drop in early, or El Nio can delay their arrival until late June.

Next page