Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2021 by Clay Coppedge

All rights reserved

First published 2021

E-Book edition 2021

ISBN 978.1.43967.316.4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021937188

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.46714.901.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

For Brigette, Tori and Josh

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A special thanks to Mike Barr, a fine writer and researcher in his own right, who first introduced me to a couple of these stories several years ago and who graciously provided photos, including the only known picture of Bill Babb that the family recognizes as authentic. A shout-out also to John and Kate Troesser at Texas Escapes, Charles Lohrmann and Tom Widlowski at Texas Co-op Power magazine and Ben Gibson, Abigail Fleming and the team at The History Press.

Some of these stories first appeared, often in different form, in Texas Co-op Power magazine and on the Texas Escapes website.

I

EARLY TIMES, EARLY CRIMES

JAMES BROCKS HONESTY OF PURPOSE

A cowboy named Frank Woosley was heading back to ranch headquarters in May 1877 after a hard day of rounding up cattle in the rough country of Shackelford County, Texas, near the town of Fort Griffin, when a depressed feeling came over him. He decided to lie down under the nearest tree to see if the feeling would pass.

Next thing he knew, it was a year later and he was in the wilds of Arkansas. He had a vague recollection of being in Jewett, Texas, for a short spell, but other than thatnothing. Frank Woosley stuck to that story for fourteen years, or maybe he made it up on the spot when the man who had allegedly murdered him in Texas called out his name and pointed a Colt revolver at him.

The man with the gun, his wrongly accused but now potentially actual killer, was a former Shackelford County rancher name James A. Brock. He didnt just happen to run into Woosley; he had been looking for him more or less continually for all of those fourteen years. Woosley had vanished so suddenly that his family back in Ohio and a majority of the people in Shackelford County thought hed been murdered. They believed Brock did it. A living, breathing (or even recently deceased) Frank Woosley would be evidence to the contrary. Now, at long last, Brock had that evidence.

Like Frank and his brother Ed, who also played a key role in the proceedings, Brock was from Ohio; he and the Woosley brothers were cousins. Brock migrated from Madison County, Ohio, in 1870, when he was twenty-five and bought a ranch on Foyle Creek. The Woosley brothers joined him a couple of years later. The three kinsmen never really got along.

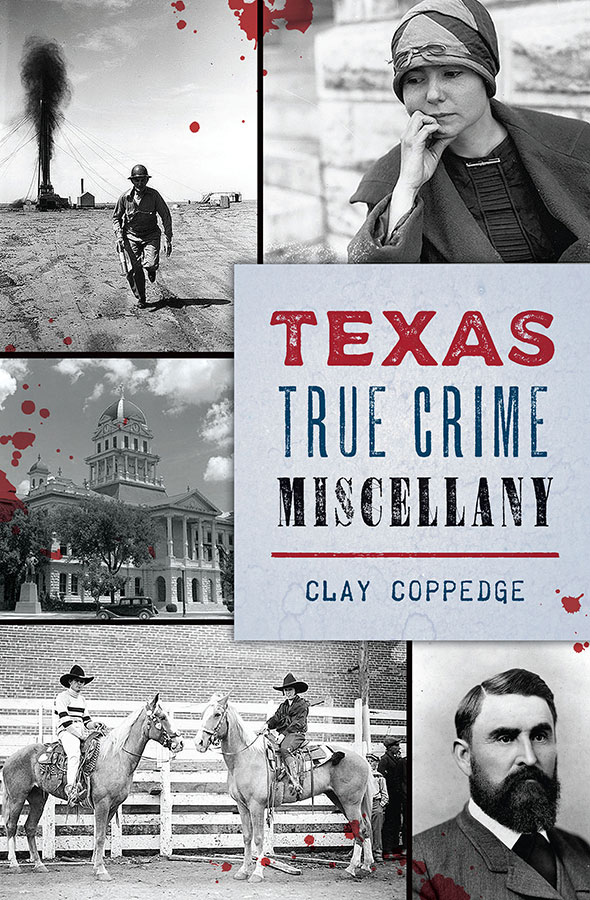

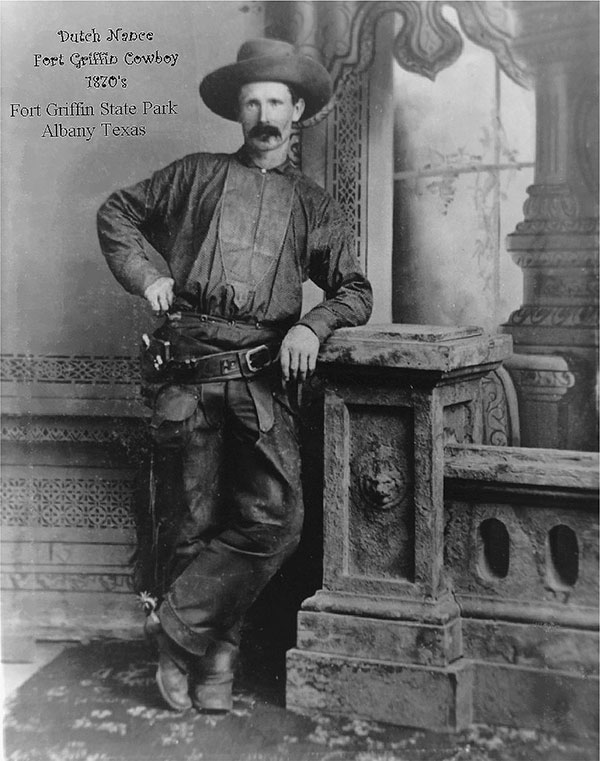

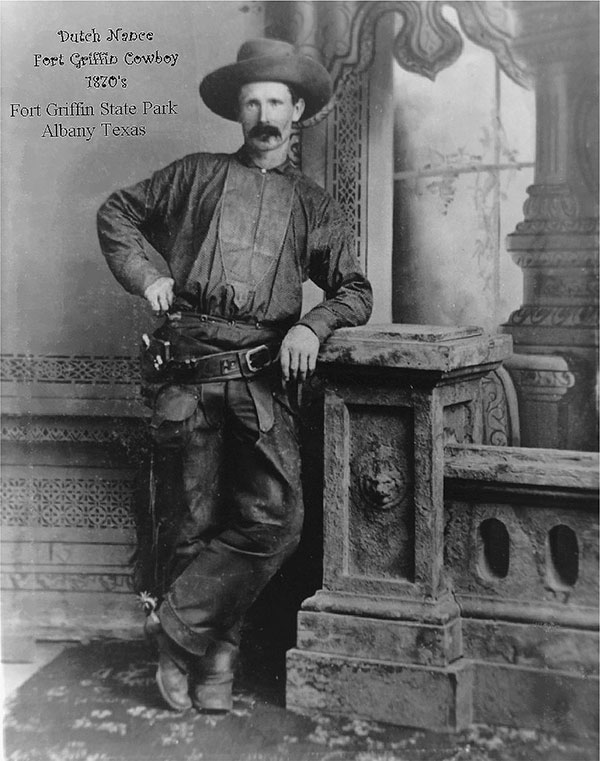

A typical Fort Griffin cowboy of the 1870s. James A. Brock wasnt a typical Fort Griffin cowboy. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Brock didnt get along with a lot of people in Shackelford County. Sallie Reynolds Matthews, who grew up on the outer limit of the northwest edge of the Texas frontier and married rancher John Matthews in 1876, wrote of Brock: He was a strange sort of person, extremely reticent and not at all friendly, the kind of person who was out of place on the western frontier and because of his peculiar nature, he was shunned by most of the people. Historian Ty Cashion noted that locals also considered his stovepipe hat and clothes out of place on the frontier.

Soon after his brother disappeared, Ed Woosley claimed that Brock had enlisted his longtime ranch hand, an African American named Uncle Nick Williams, to kill Frank. Ed and a group of vigilantes took Williams into their custody and promised him immunity in exchange for his testimony against Brock. He refused. You cannot force me to tell a lie, he told the men, and that was the truth. The vigilantes tied a rope around his neck and strung him up to hangthree timesbut he never relented. They finally let him go.

Not accustomed to waiting around for trials, and usually having their own way in Shackelford County, a particularly nasty and prolific group of local vigilantes decided to lynch Brock anyway. The Texas Rangers, called in to quell the regions rising tide of vigilantism, were on hand to make sure Brock had his day in court.

At his trial, Brock insisted, as he had from the beginning, that not only did he not kill Woosley, neither had anyone else. Woosley was alive, he claimed, and his disappearance was a circumstantial frame job by the Woosleys to lay hands on Brocks land and money. Frontier journalist Don Hampton Biggers noted that Brock and the Woosleys peculiar business arrangement stipulated that if Brock died from any cause, natural or otherwise, the Woosleys would get all the property.

To eleven of the jurors, Brocks story sounded like a wild conspiracy theory cooked up by a desperate man; they voted to hang him. The twelfth juror begged to differ, pointing out the glaring absence of a body as an absence of proof. The judge dismissed the charge and released Brock, but people in Fort Griffin and Ohio believed Brock got away with murder. As for the ranchers, they never much liked him anyway.

Some of Brocks fellow stockmen soon accused him of sequestration, a fancy word for cattle theft. Three such cases dragged on for three years at a time when the cattle business in Shackelford County was flourishing. But Brock spent most of that time and a good deal of his money battling the accusations. The courts found him not guilty on all charges.

Soon after Ed Woosley died of natural causes in 1880, Brock sold his ranch and left town to look for the man who stole his reputation, spending all his money and working at any job he could find to finance the quest. He settled in El Paso in 1884 and began selling real estate, but he never stayed so busy he couldnt leave town at a moments notice to investigate the latest alleged sighting of Frank Woosley.

Those who said Brock was obsessedand many people didwere not exaggerating. He flooded the country with pictures of the alleged murder victim, offered $1,000 for information leading to Frank Woosleys discovery, dead or alive, and followed leads, tips and alleged sighting to towns and outposts across the country. None of them panned out.

In June 1891, a detective named G.B. Wells wrote a telegram to Brock saying he had spotted Woosley in Arkansas. As he had done so many times before, Brock hurried to check out the latest tip only to find that, once again, he had trailed the wrong man. Another dead end.

Brock, Wells and the local sheriff had dinner in Searcy, Arkansas, before boarding a train to Memphis, never suspecting that Frank Woosley was riding the same train. At Augusta, Arkansas, Brock decided to surrender his six-shooter to the railway agent rather than take it to town, where carrying a firearm was illegal. He approached the agent and was about to unbuckle his gun belt when he glanced out the window and saw Frank Woosley, live and in person, standing next to the platform. His heart started beating real fast. He held on to his gun.

Next page