Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

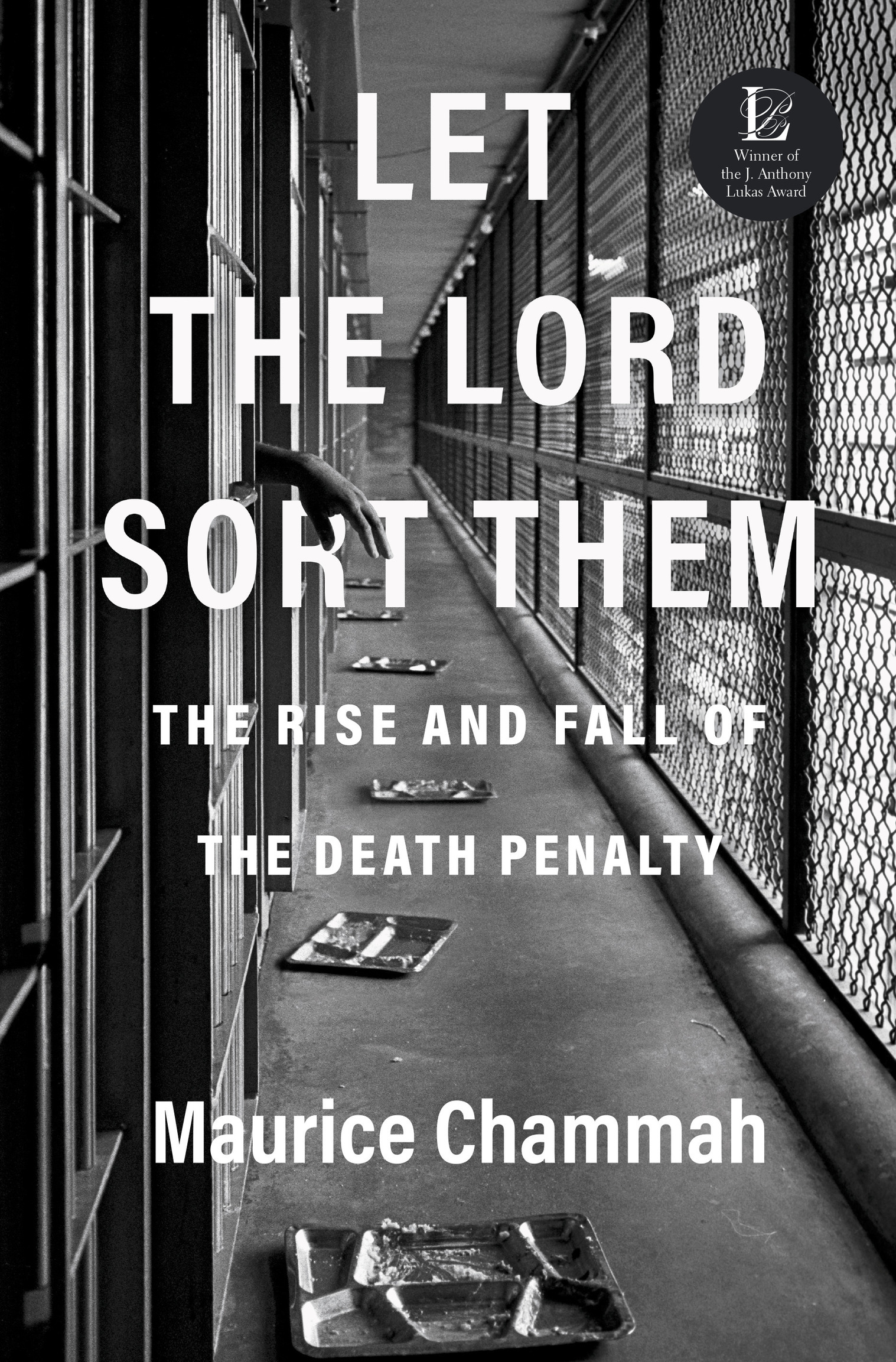

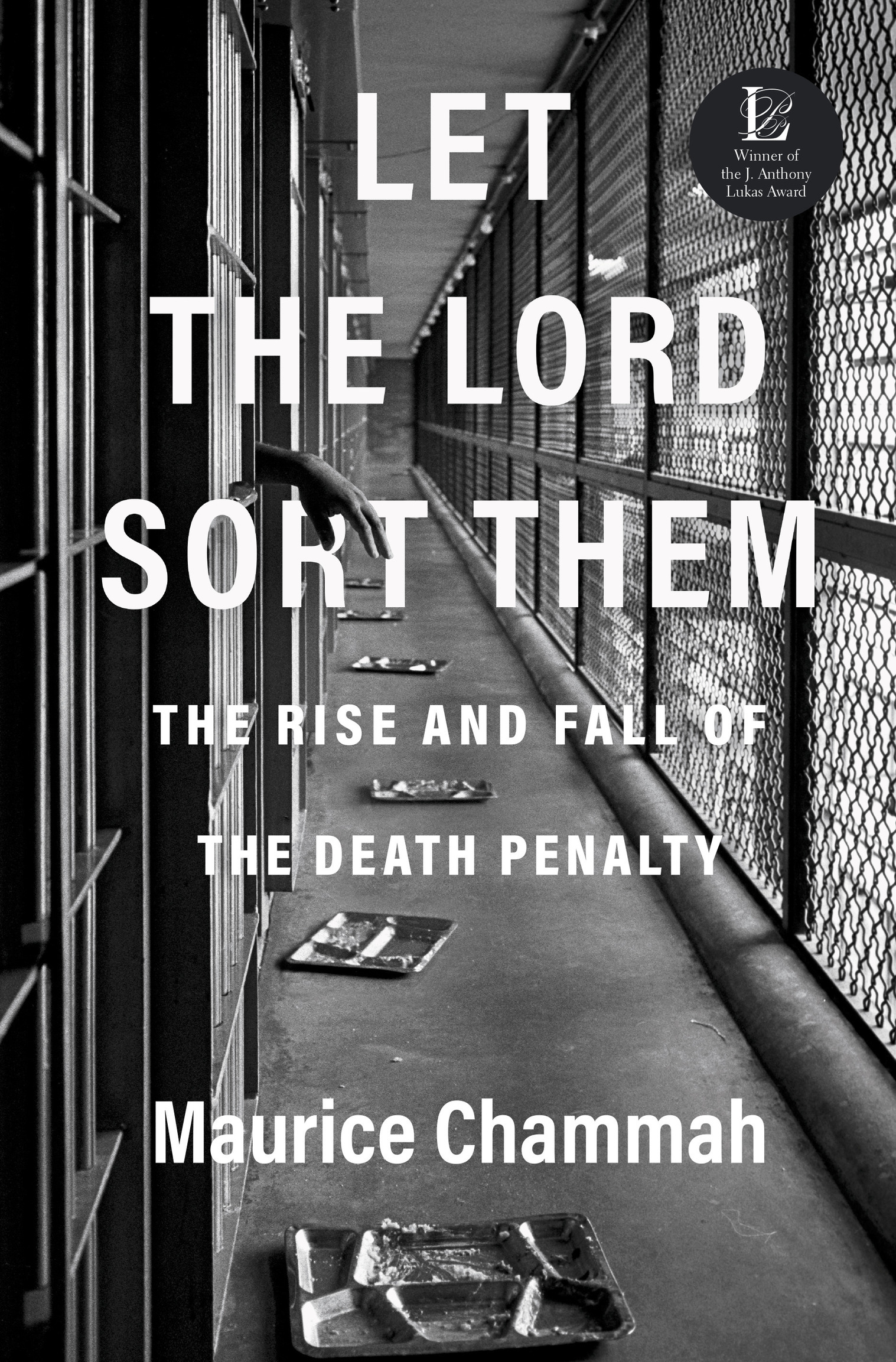

Praise for

LET THE LORD SORT THEM

Let the Lord Sort Them gives us the story of the death penalty through the eyes of the attorneys, legislators, judges, criminals, and victims for whom one of our oldest and most contentious policy debates became frighteningly real. Its a wonderfully written blend of history and reportage, delivered with sensitivity and grace.

Nate Blakeslee, New York Times bestselling author of American Wolf and Tulia

Its impossible to understand the death penalty in America without understanding the death penalty in Texas. Maurice Chammahs lyrically written, meticulously researched volume does more to advance our understanding of the states peculiar devotion to executions than any book before it.

Evan Mandery, author of A Wild Justice: The Death and Resurrection of Capital Punishment in America and professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Of the many books about capital punishment in the United States and in Texas in particularsome focused on players in the system, including both executioners and executed offenders, and some focused on the chasm between the legal system we have and the legal system that death penalty law promisesno volume I know of succeeds in weaving together these two orientations as seamlessly as Maurice Chammah has here. The result is a singularly illuminating book. Nobody, neither death penalty supporter nor abolitionist, will come away from Let the Lord Sort Them without having her or his belief in the fairness of the death penalty system utterly shaken if not entirely destroyed.

David R. Dow, author of The Autobiography of an Execution and Cullen Professor at the University of Houston Law Center

A nuanced and deeply reported account of evolving attitudes toward the death penalty in Americaa thorough, finely written, and unflinching look at one of the most controversial aspects of the American justice system.

Publishers Weekly

[A] nuanced look at the complex history of the death penalty[Chammahs] outstanding storytelling and thorough research make this an excellent analysis of modern legal and criminal-justice history.

Booklist

Copyright 2021 by Maurice Chammah

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Crown and the Crown colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to The Texas Observer for permission to reprint portions of To Kill or Not to Kill? (April 23, 2014). Copyright Texas Observer.

Portions of this work originally appeared, in different form, in the following publications: The Slow Death of the Death Penalty (December 17, 2014) and How Mexico Saves Its Citizens from the Death Penalty in the U.S. (September 22, 2016) in The Marshall Project (themarshallproject.org), and Executions Are So Common, Even Protesting Them Has Become Routine (November 12, 2013) in Texas Monthly.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Chammah, Maurice, author.

Title: Let the Lord sort them / Maurice Chammah.

Description: First edition. | New York: Crown, [2021] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020025171 (print) | LCCN 2020025172 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524760267 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781524760274 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Capital punishmentTexasHistory20th century. | TexasPolitics and government1951

Classification: LCC HV8699.U6 T435 2021 (print) | LCC HV8699.U6 (ebook) | DDC 364.6609764dc23

LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2020025171

LC ebook record available at lccn.loc.gov/2020025172

Ebook ISBN9781524760274

crownpublishing.com

Book design by Jo Anne Metsch, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Cardon Webb

Cover photograph: Bruce Jackson

ep_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

Contents

PROLOGUE

ONE AFTERNOON IN NOVEMBER 1982, Warden Jack Pursley called a meeting of his senior staff. Pursley ran the oldest prison in Texas, which is located a few blocks from the courthouse square in Huntsville, a small city in the eastern part of the state. The Huntsville Unit is nicknamed the Walls because of the tall red brick fortifications that surround its grounds. (The bricks were made by prisoners.) Across the street stood the offices of the Texas Department of Corrections, the agency overseeing the states prisons. On one side of the street, Pursley gave orders; on the other side, he took them.

The staff had all been told of this meeting by phone rather than the usual written memo, and when unit chaplain Carroll Pickett arrived, he immediately noticed a pinched mood. The typical coffee and doughnuts were absent. Pickett asked the head of the maintenance crew what this was about. He didnt know, and together they asked a major, who didnt know either. After fifteen minutes or so, Pursley appeared, wearing his usual suit, boots, and Stetson hat. His face was grim. As he passed by Pickett, he murmured, Youre not going to like this.

Pursley removed his hat and set it down. We will soon be having an execution, he said. December 7, shortly after midnight.

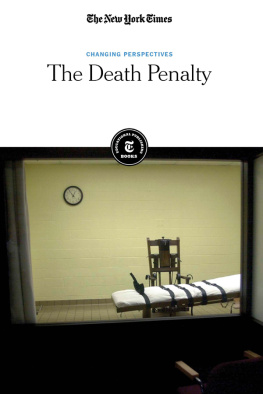

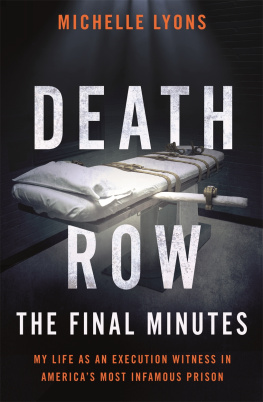

Many years later, Pickett could remember the stunned silence in the room, the knots in his own stomach. The last time an execution had taken place here was eighteen years ago, and nobody in the room had been around back then. In the intervening years, legal challenges had halted all executions, forcing the state legislature to write new capital punishment laws in 1973. The new death row prisoners began filing appeals. In the meantime, Pursley had been asked to fix up Old Sparky, the states electric chair. His work turned out to be unnecessary; the chair was now stored in a wooden crate. State legislators feared electrocutions would be too much of a spectaclea circus sideshow, one called itso in 1977 they adopted a new execution method called lethal injection. Though the procedure had been developed in Oklahoma, Pursleys team would be the first in the country to put it into practice. Sodium thiopental, a barbiturate, would render the prisoner unconscious. Pancuronium bromide, a paralytic, would freeze his respiratory muscles. Finally, potassium chloride would stop his heart.

I dont know a thing about what weve got to do, Pursley told the group. All of us have a great deal of learning to do in a short period of time. He read tasks off a clipboard. Two men would greet the condemned man at the death house. A tie-down team would strap him to the gurney. Others would load the body into a hearse and accompany the vehicle to the prison gate.

The warden led the men through heavy iron doors and into the old death house. They walked through a hallway, past several small cells where men had once spent their final days. The atmosphere reminded Pickett of a medieval dungeon: The walls were painted gray, and there was little ventilation, making it feel as if all of the air had somehow been sucked out of the room. Through another iron door was the death chamber, where Pursley showed them a wheeled stretcher with large leather straps laid across it. (Later, a gurney would be bolted to the floor.) Pickett noticed three small windows, framed in mint green, behind which the executioners would send the chemicals down tubes connected to an IV line.