dog company six

DOG COMPANY SIX

Edwin Howard Simmons

Naval Institute Press

Annapolis, Maryland

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2000 by Edwin Howard Simmons

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-61251-160-3

07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

First printing

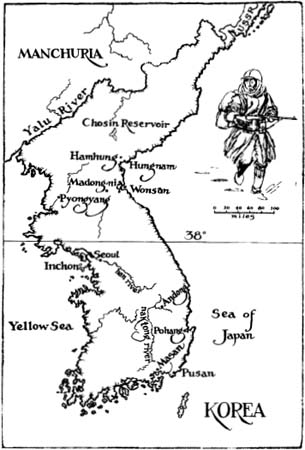

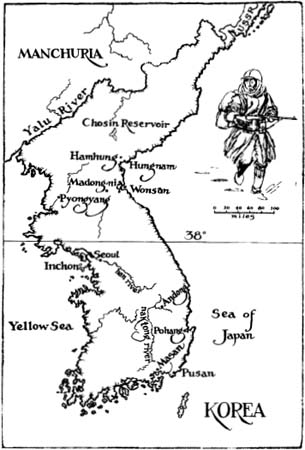

Map drawn by Charles Waterhouse

The electronic version of this book was brought to publication with the generous assistance of Edward S. and Joyce I. Miller.

For all the marines who served

in the Korean War

Contents

Bayard regarded his outstretched legs with a great deal of interest. They were floating in front of him like two silver-white fish on the surface of the rusty-red water. All his civilian fat was gone. The legs were thin, and the wet, white skin was stretched tight against the bone and muscle. He must look, he decided, like one of El Grecos gaunt and attenuated figures.

Bayard was in his bathtub.

He had been wounded in April; it was now June. This was the Hotel Otsu on Lake Biwa, a few miles from Kyoto. He had arrived at the Otsu that afternoon. The hotel had been built, he supposed, twenty or thirty years ago for the American and European tourist trade. Now its shabby elegance was made available to dependents, special visitors, transient officers, and convalescents through the good offices of U.S. Army Special Services, Far East Command.

The porcelain of the tub was cracked and stained. The shoddy Oriental imitation of Western plumbing creaked and groaned and worked its secrets spasmodically. Above the chipped and broken shoulder-high tile, the walls and ceiling were painted a strident yellow. The underpowered electric lightbulb hanging bare from its cord glowed a sullen brown.

But the water was hot, and this was the bath he had promised himselfthe long, hot soaking that would wash away the ingrained pore-deep smells of Korea and the overlying antiseptic and fecal odors of the hospital.

The soaking went on for a long time. At last Bayard broke free from the lethargy induced by the bath and climbed reluctantly from the tub. He stood in the center of the tiny bathroom and rubbed dry with the thin and slightly stale towel, examining his bare body as he did so with the diligent curiosity of a child.

He dried his legs thoughtfully. They were oddly smooth. Then he remembered that the months of living in woolen underclothing had worn off the body hair.

The scar from his wound crawled like a many-legged red lizard from the angle of his hip to the lower edge of his ribs. The surgeon in the Yokusuka hospital had said, If that piece of grenade had been one inch this way or that.

Still naked, Bayard moved over to the washbasin, where he had laid out his shaving things. He studied his face critically in the mirror. The skin lay firm and clear against the bone. The red windburn had changed in the hospital to a deceptively healthy-looking tan. But his eyes were still tired, and his brown hair, cut to regulation length this afternoon by the hotel barber, was beginning to show streaks of gray.

If it had been an American-made fragmentation grenade, it probably would have killed all three of them. As it was, the casing had been poorly cast in some Chinese foundry, and half of it in one large fragment had ripped across Bayards abdomen while the rest shivered into pinpointsized splinters that had peppered Baby-san and Havac.

Bayard shaved carefully using a new blade, combed his hair, and then went into the bedroom. He put on a new set of cotton underwear. The drawers were his regular size, but they were too big and to hold them up he had to tighten the tapes on the sides all the way. In the nine months between Inchon and now he had lost twenty pounds.

The mama-san who looked after his room had brought his uniform from the tailor shop, and it lay on the bed, the green kersey jacket and trousers neatly pressed. The uniform was enlisted issue, and the cloth felt stiff and unfamiliar. The green wool would be hot and uncomfortable on a June night, but his summer service tropical worsteds were lost, along with the rest of his officers uniforms.

The lieutenant in charge of the warehouse had been more than apologetic for the loss. He had been practically grief-stricken. He insisted on showing Bayard that the divisions personal effects were now all neatly sorted and stacked, tagged and palletized. Everything was very systematic.

But, the lieutenant had said, you remember the helter-skelter confusion of seabags and footlockers you left behind on the Kobe docks when you loaded out for Inchon in September. Then there was the typhoon, and later some of the baggage was pilfered by the dock workers before things were gotten under control. And, for a while during the worst part of the Chosin Reservoir in December, the casualty reporting system had broken down and some of the division personnel had been mistakenly reported dead or missing in action and their personal effects sent prematurely to their dependents in the States.

Bayard had listened politely to the lieutenants explanations. The term personal effects bore a nice, clean antiseptic quality. A mans belongings were reduced to a neatly typed inventory and a carefully packed box. Before shipment any items of government property and all such things as condoms and pornographic pictures were removed so that what the dependents received of their sons or husbands belongings was sterile and immaculate and something like a retouched photograph.

Bayard didnt much care that his own things were missing. What was it he had lost? There was nothing, as he remembered it, that really mattered in the trunk, just his uniforms, some insignia, a few books he might have read again, some old letters, and a cheap camera.

And the large photograph of Donnaa Harris and Ewing photographyounger and perhaps better looking than she really was. But he didnt need a photograph to remember Donnas tall, full-curved figure, her warm chestnut hair, or the faint violet shadows under her eyes.

Gratuitous issues of clothing were supposed to be made only to enlisted marines, but the lieutenant seemed to feel he had to make up for the loss of the trunk. Bayard accepted just what he thought he would need for the trip home. Then he had gone to the army PX in downtown Kobe and bought himself a new set of insignia and ribbons and a few other essentials.

Now, in his hotel room, Bayard pinned onto the green jacket his silver captains bars, the bronze Marine Corps insignia, and the two rows of World War II ribbons, now topped off with the Silver Star and the gold-starred Purple Heart.

That twice-awarded Purple Heart was his ticket home. Two wounds requiring hospitalization, and back to the States you went. That was Marine Corps policy. He would finish his convalescent leave, present his orders for endorsement, and get air transportation back to the continental United States. His ribbons were his passport. He had done his share. No further explanations were required. No apologies to anyone. None needed. He didnt owe anything to anybody.

Dearest Donna, he had written from the hospital just before his release,

Please thank your father for his offer to contact the Secretary of the Navy but it isnt necessary. I am practically home. Everything has been repaired. You have nothing to worry about. All the essential parts are functioning perfectlya fact which I will demonstrate to you at the earliest opportunity. Also I have a very handsome scar. Unfortunately the damned thing is located where only my very best friends will ever see it.

Next page