ALSO BY HAMPTON SIDES

Stomping Grounds

Ghost Soldiers

Blood and Thunder

Americana

Hellhound on His Trail

In the Kingdom of Ice

Copyright 2018 by Hampton Sides

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

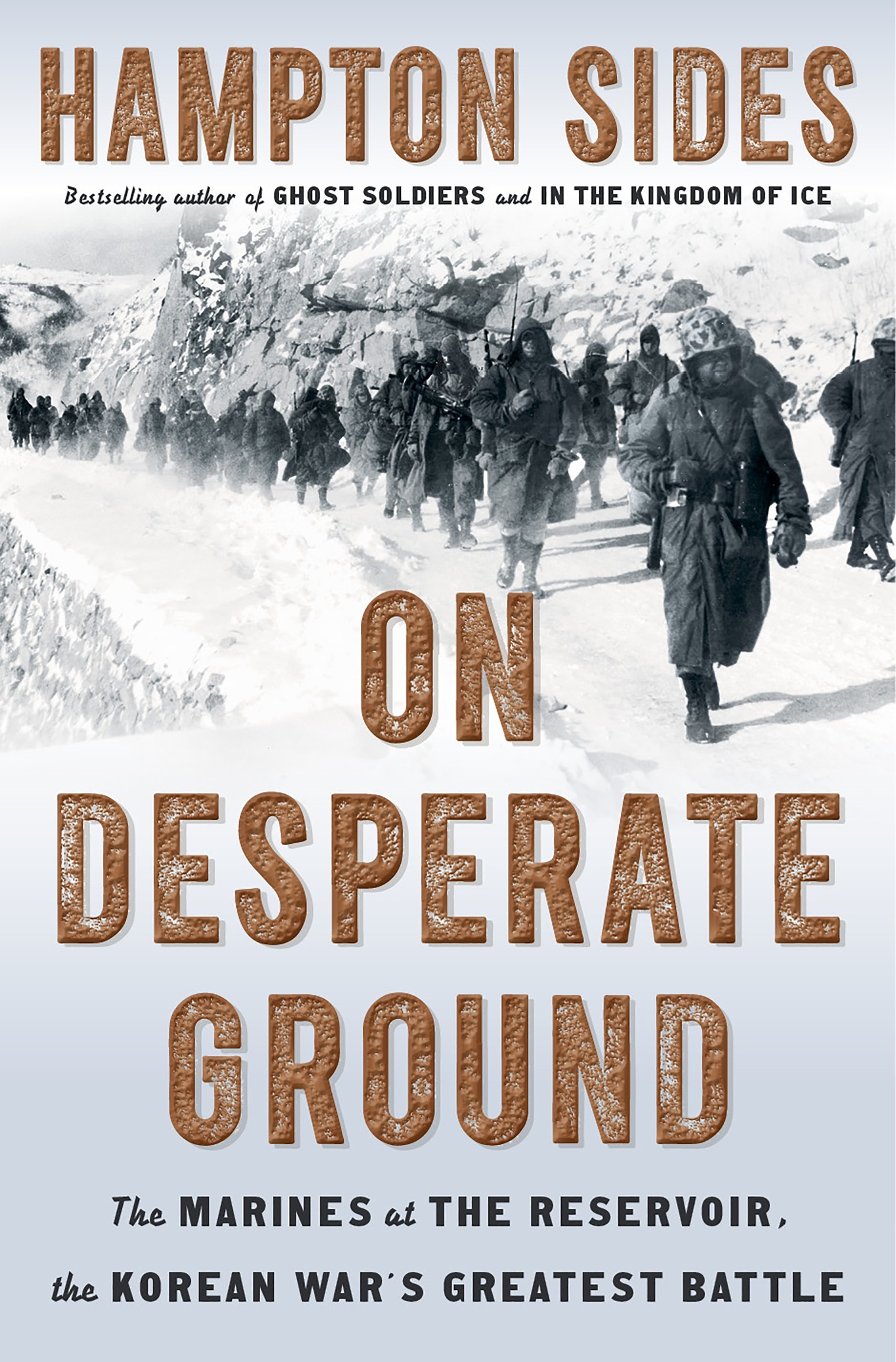

Cover image: U.S. troops march south from Koto-ri during the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, Korea, December 9, 1950. PhotoQuest / Getty Images

Cover design by John Fontana

Names: Sides, Hampton, author.

Title: On desperate ground : the Marines at the reservoir, the Korean Wars greatest battle / Hampton Sides.

Other titles: Marines at the reservoir, the Korean Wars greatest battle

Description: First edition. | New York : Doubleday, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018010543 | ISBN 9780385541152 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780385541169 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Korean War, 19501953CampaignsKorea (North)Changjin Reservoir. | United States. Marine Corps. Marine Division, 1stHistory. | Changjin Reservoir (Korea)History, Military20th century.

Classification: LCC DS918.2.C35 S53 2018 | DDC 951.904/242dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018010543

Ebook ISBN9780385541169

v5.3.2

ep

WALKER AND MACK

And the steadfast men of the Korean War Generation

Sun Tzu says that in battle there are nine kinds of situations, nine kinds of ground. The final and most distressing type is a situation in which ones army can be saved from destruction only by fighting without delay. It is a place with no shelter, and no possibility of easy retreat. If met by the enemy, an army has no alternative but to surrender or fight its way out of its predicament.

Sun Tzu calls this desperate ground.

Contents

PROLOGUE

MORNING CALM

In the misting rain, they pressed against the metal skins of their boats and peeked over the gunwales for a glimpse of the shores they were about to attack. Some thirteen thousand men of the First Marine Division, the spearhead of the invasion, had clambered down from the ships on swinging nets of rope and then had crammed themselves into a motley flotilla of craft that now wallowed and bobbed in the channel. Several of the rusty old hulks, having been commandeered from Japanese trawlermen, smelled of sour urine and rotten fish heads. The Marines, many of them green from seasickness, saw the outlines of the charred foothills that rose above the port, and caught the scent of the brackish marshes and the slime of the mudflats. Corsairs, bent-winged like swallows, dove over the city, dropping thousand-pound bombs and sending five-inch rockets deep into hillside nests where the enemy was said to be dug in. Far out at sea, the naval guns rained fire upon the city, damaging tanks of butane that now flared and belched palls of smoke.

On this warm, humid morning of September 15, 1950, the Marines had arrived at their destination halfway around the world, to stun their foe and turn the war around: a surprise amphibious attack, on an immense scale, deep behind the battle lines. Only a few months before, these young men, fresh from their farms and hick towns, had piled into chartered trains and clattered across America to California. Then they climbed aboard transport ships, where many of them did their basic training, learning how to strip and rebuild M1 rifles, drilling on the crowded decks, practicing their marksmanship on floating targets towed from the fantails. They crossed the Pacific and stopped briefly in Japan, then heaved their way through a full-scale typhoon. They rounded the peninsula and moved in convoy up the west coast, through the silted waters of the Yellow Sea.

By the thirteenth of September the ships had begun to concentrate, 261 vessels in all, carrying more than 75,000 men and millions of dollars worth of war matriel. On the fourteenth, the armada was closing in on its target: the narrow confines of Flying Fish Channel. The channel led to Inchon, an industrial city of a quarter million people, whose strategically vital but treacherous port served the capital, Seoul.

On the morning of the fifteenth, in the seas west of Inchon, the ships ranged along the horizon, a long line of gray bars stitching through the mist. First came the destroyers Swenson,Mansfield, DeHaven. Then the high-speed transports Wantuck, Horace A. Bass,Diachenko, and the dock landing ship Fort Marion. Then the heavy cruisers Toledo and Rochester and three more destroyers: Gurke,Henderson, and Collett. Following in their mingled wakes came the British light cruisers Kenya and Jamaica, the attack transports Cavalier and Henrico. Farther out at sea lay the fast carriers, from which the Corsairs rose into the skies to make their deadly sorties.

By afternoon, as the Marines drew near the Inchon seawall, enemy rounds zinged across the water surface and mortar shells crashed haphazardly all around. Within a few minutes the Marines would reach the cut-granite ramparts. They would climb over, and they would set foot on the western shores of central Korea.

What was Korea to these young men? Some fate-ravaged place, an inflamed appendix, a wattle of real estate flapping off the face of the mainland. Though some of the units approaching Inchon had spent the past month bolstering United Nations forces at the southern tip of Korea, most of the First Marine Division had no experience with the country. They had little knowledge of Koreas tragic history, no appreciation for how faithfully this proud culture had held on through centuries of turmoil and besiegement. It was a small nation that history had pushed arounda shrimp among whales. The Mongols had had their way with her, the Manchus, the Russians, the Japanese. Now had come the Americans, nervous young men who knew next to nothing about the place, though some had passed around guidebooks filched from hometown libraries.

Korea, theyd learned, was known as the Hermit Kingdom. The Land of the Morning Calm. Its national dish was a hot mess of fermented cabbage. Some Marines had read with astonishment that in parts of Korea, peasants still nourished their crops with night soil and were known to roast the occasional hound for dinnerthese were some of the clichs that were passed around. Korea was said to be a dirt-poor country, mountainous, swept by Siberian winds, sultry during summer and breathtakingly cold in winter.

But what did the travel manuals really know? God created war, Twain wrote, so that Americans would learn geography, and the men of the First Marine Division were about to learn a lot about this tough, sorrowful scrap of land. While some would find a deep affinity for it, many would come to hate it, for all the things it was and for all the things it wasnt. But to most of them, more than anything, Korea just seemed a long way from homea long way to come to fight and bleed and die, in a war that was not officially a war, for a cause that at times was not altogether clear, for an endgame that was anybodys guess.