L OUISIANA PLACE NAMES

L OUISIANA PLACE NAMES

Popular, Unusual, and Forgotten Stories of Towns, Cities, Plantations, Bayous, and Even Some Cemeteries

C LARE DA RTOIS L EEPER

L OUISIANA S TATE U NIVERSITY P RESS

B ATON R OUGE

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2012 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing

DESIGNER: Michelle A. Neustrom

TYPEFACE: Garamond Premier Pro

PRINTER AND BINDER: Sheridan Books, Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Leeper, Clare DArtois.

Louisiana place names : popular, unusual, and forgotten stories of towns, cities, plantations, bayous, and even some cemeteries / Clare DArtois Leeper.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8071-4738-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8071-4739-9 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8071-4740-5 (epub) ISBN 978-0-8071-4741-2 (mobi) 1. Names, GeographicalLouisiana. 2. LouisianaHistory, Local. I. Title.

F367.L425 2012

910.01'409763dc23

2011048188

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

To the memory of my grandmother, Ora Wakeman Gladney, and of her grandfather, William H. Tunnard

I was not sure I understood, and asked her with a childs exasperation why she always needed to give me the old meanings of words, why couldnt she simply tell me what a word meant today? And she said, patiently, Everything has a name, and names are very important. Nothing exists unless it has a name. Can you think of something that doesnt have a name? And, everything has a past. Everythinga person, an object, a word, everything. If you dont know the past, you cant understand the present and plan properly for the future. We are going to build a new world, Ilana. How can we ignore the past?

CHAIM POTOK, Davitas Harp

C ONTENTS

P REFACE

M y great-great-grandfather W. H. Tunnard worked for or contributed to the major newspapers of the day, including the Shreveport Times, where he was editor. He also wrote a memoir of his experiences in the Civil War, A Southern Record: The History of the Third Louisiana Regiment.

W. H.s daughter wrote poetry and nostalgia pieces for the newspaper under the name Eulalie. When she died of consumption at age thirty, her daughter Ora became part of her grandfather Tunnards household.

Pa was clearly Oras hero, and she often recounted for her grandchildren and great-grandchildren the story of his familys coming south from New Jersey when he was two years old. At Kenyon College in Ohio, he studied to be an Episcopal minister. But instead he embarked on a career as a journalist, writing for the Baton Rouge Gazette and Comet.

Ora loved to tell stories about her grandfather: he was the most popular man in his regiment during the siege of Vicksburg because he owned a rat terrier that provided food for the starving men; throughout his life, he maintained many Confederate friendships from the war. She also talked about his newspaper work, which included organizing the Louisiana Press Association.

W. H. assured his multigenerational family the opportunity to know more about where Ora was born by giving her A Souvenir of the City of Shreveport, a lithographed silk handkerchief dated 1887, the year she was born. The handkerchief, imprinted by the A. Gast Bank Note and Lithographing Company, depicts thirteen scenes of Shreveport from that time.

One vignette is of the New Opera House, where the young Ora accompanied her grandfather to performances by Sarah Bernhardt, Amelita Galli-Curci, and Enrico Caruso. Other buildings she visited with Pa were the First National Bank, the U.S. Custom House and Post Office, Florsheim Bros. Furniture Store, Aug. J. Bogels Drug Store, and the Railroad Station. But Ora never mentioned going to the Racetrack or the Cat Fish Hotel.

Although Ora obviously admired Pas talent, she never suggested that any of us become a writer. Nevertheless, her daughter, granddaughter, and great-grandson all followed W. H. Tunnards lead by writing for newspapers.

P UBLISHER S N OTE

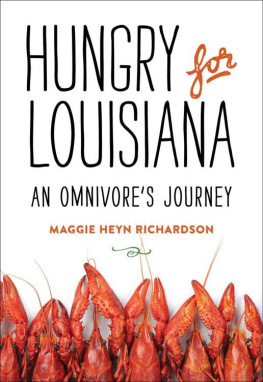

Louisiana Place Names is the result of the authors many decades of research both in the written record and in the wealth of legend, oral tradition, and folklore surrounding the origins of Louisiana place names. The highly personal nature of this journey means that the author has pursued some topics in more depth than others, and not every Louisiana place name is represented here. Looking into the derivations of place names is an organic and ongoing process, and this books gift to future generations is to assemble in one volume a lifetimes work of listening to, gathering, and transcribing the accumulated information we have about how our towns, cities, bayous, and other places came by their names.

L OUISIANA PLACE NAMES

I NTRODUCTION

F ebruary 7, 2011, marked fifty years since my first column called Louisiana Places: Those Strange Sounding Names appeared in the Baton Rouge Sunday Advocate. Shortly thereafter, the columns also began to run in the Sunday editions of the Shreveport Times, the Monroe News-Star, and the Lake Charles American Press.

In 1976, as part of the bicentennial celebration, I published the columns in a hardcover limited edition of one thousand copies; it was soon out of print.

I continued to write the column until I reluctantly gave it up in 1979. I resumed writing it in 2004. The date of my last column was August 13, 2006.

As a young freelance writer, I first conceived the idea of writing about place names while acting as a family tour guide in south Louisiana in the late 1950s. Armed with a road map and the classic book Louisiana: A Guide to the State, our family, with visiting Tennessee in-laws, set out on one of its day trips. The Guide was a wonderful companion if you took the tours it laid out, but if you wanted to go down other roads you were on your own. We were disappointed when we visited places that were not included in the book. Nevertheless, on that hot summer day, after reading the Guide and traveling the roads of Louisiana, I realized that place names contain a special and often unrecorded view of our history, and I knew that I wanted to write about them.

The following week, I pitched the idea to an editor who worried that there was not enough material to sustain a weekly column. To ease his concern, I prepared twelve sample columns, three months worth, and submitted them with my proposal to the publisher. After some weeks, the proposal was accepted. My first column, about Natchitoches, appeared on February 7, 1961.

During the years since I began writing the column, place-name research has undergone revolutionary changes brought on by communications technology, the Internet, and the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). Before these innovations were available for widespread public use, place-names research was limited to personal interviews, letters sent via U.S. mail, and visits to courthouses, museums, libraries, and place-name sites. Researchers can still use those resources, but they can also access the Web sites of cities, towns, villages, unpopulated places, historic sites, and numerous other sites, such as those for airports, cemeteries, churches, dams, and schools. Library archives, catalogs, and collections make sources accessible that may not easily be found in an old-fashioned card catalog. These new information technologies help, but they do not change the challenge.