Table of Contents

Guide

Table of Contents

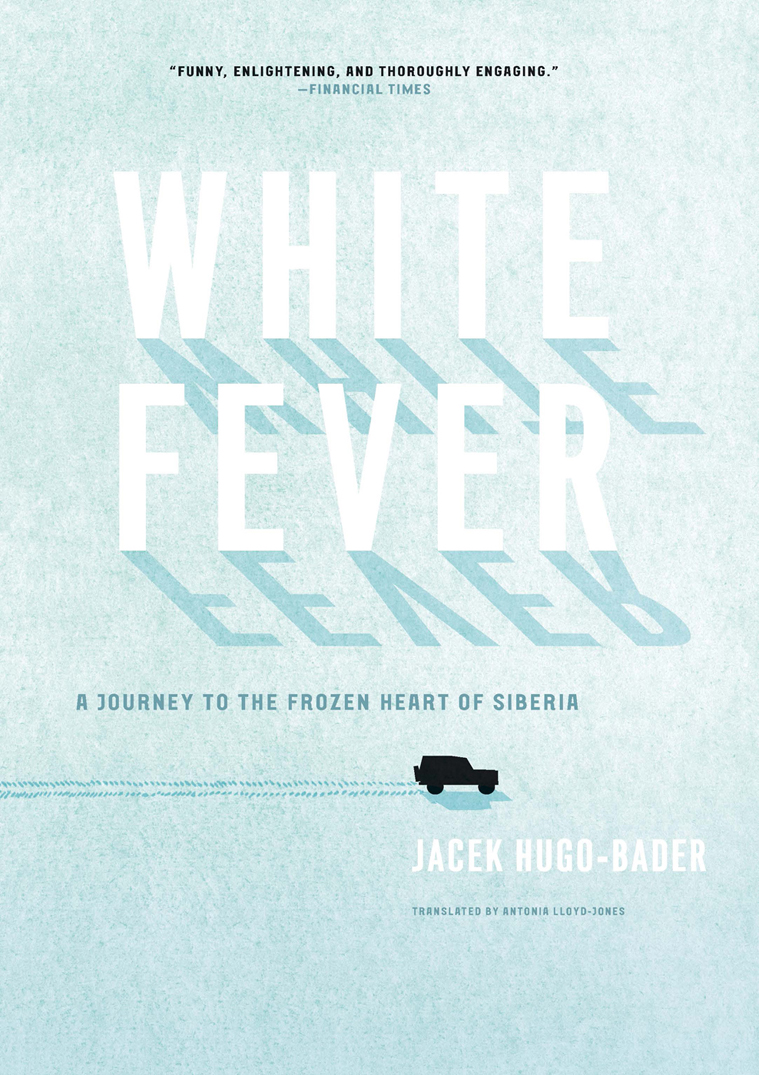

Chin Li, the wandering Chinese man somewhere near Novosibirsk.

Bonnet into the wind

My only prayers were not to break down in the taiga at night, and not to run into any bandits. I was ready for the first of these misfortunes, but not for the second. I must have been the only madman to travel across that terrible ocean of land without a weapon, and on my own into the bargain.

The locals favourite sport is shooting. They drive normally, on the right-hand side of the road, but theyve got the steering wheel on the right too, because the cars are imported from Japan. They hold it in their left hand, so they can easily stick the right one out of the window and blast away, while on the move, with whatever weapon they have, at road signs, adverts and notice boards.

In eastern Siberia I didnt see a single road sign that wasnt as full of holes as a colander. Large and small bores, single shots and whole bursts, and even some huge holes made by a heavy shotgun.

And every few dozen metres theres the wreck of a burned-out car.They must have broken down in the winter, at night too, and their desperate owners set them alight to keep warm.

Theres little chance this would have helped them to survive.

NIGHT

What idiots. Before leaving they should have found out how to survive a winters night in the taiga.

I always stop the car with the bonnet facing into the wind, just in case. If its blowing from another direction, it can pump poisonous exhaust fumes inside.

I keep the engine idling to warm the car up. It wont run out of fuel, because it only uses about a litre an hour, and the tank is always at least half full.

This is the most sacred principle of travelling by car across Siberia in winter keep filling up, so youve always got at least half a tank of petrol. However, before lying down to sleep I always switch off the engine theres too big a risk of the wind changing direction during the night, in which case Ill never wake up again. But I set the alarm in my phone to wake me every two hours, then I get up and start the car, leaving it running for ten to fifteen minutes. Its not even to warm up the cab, but to keep the engine and the oil sump from freezing, and to charge up the battery. At minus thirty degrees youve no chance of the car starting in the morning without these manoeuvres, because the engine oil goes as dense as plasticine. I once tried adding it to the engine at that sort of temperature, and while I was about it, I tried to top up the brake fluid and the power steering fluid too. They were all so thick they refused to come out of the bottles.

But suppose the phone battery ran down and I didnt wake up until morning? Then Id have to light a bonfire. Of course no-one in their right mind travels across Siberia without an axe. You chop some firewood and pile it up, but you cant even light it with petrol because its terribly cold and windy, and everythings covered in snow. I took a jar with me containing a special mixture of petrol and engine oil in proportions of one to one. Even wet wood will catch light if you pour that on it.

However, suppose I got stuck in the steppes beyond Baikal, not in the taiga? Theres no kindling there. But Ive brought some with me. Im actually carrying a box of wood from Europe all the way across Siberia, not for warming my hands, of course. You have to put the bonfire on a shovel (which is just as vital as the axe) and stick it under the car to heat up the engine, and above all the oil sump. I can just as well do it with a petrol burner its a very simple device, a bit like a small flame-thrower, which I bought at a scrap-metal shop for 600 roubles (12).

But suppose the frost is so awful and youve slept so long that the battery has gone dead? Easy Ive got a second one, in the cab, where its much warmer. I dont even have to shift it, because its joined to the first one by cables. I only have to flick a switch.

But suppose the engine thats keeping you warm has broken down? Youve got to survive at least until morning. In fact the Siberians have a saying that in their country you dont even leave an enemy alone in the taiga, but that doesnt apply to the road situation or nighttime. The traffic volume is much lower, though it doesnt stop entirely, but there is no force strong enough to make the Russian driver stop after sunset. Theyre afraid of bandits.

The best solution is a vebasto, an independent heater driven by a small combustion engine, which heats separately from the workings of the car. It costs 1000 Euros, so I didnt indulge myself by getting one, but instead I have a small portable camping stove that I light in the cabin, and before going to sleep I turn it off, to save gas. At night Im warmed by one or two candles that I stand on the floor. On the coldest night I spent in the car, the temperature at dawn fell to minus thirty-six degrees, but in the cab it was only minus fifteen.

Of course Ive got a wonderful down sleeping bag and a down jacket, and I always keep enough food and drink for several days.

DREAM

In March 1957, possibly on the 9th at one in the afternoon, because Saturdays were when the science department of Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper held its weekly meetings, two reporters were given an unusual assignment by the editor-in-chief. (On that day and at that time, on the polished wooden floorboards between the kitchen and the bedroom in my grandmothers flat at 62 Warszawska Street in Sochaczewo, rather unexpectedly, I made my entrance into the world.)

We must tell our readers about the future, said the editor-in-chief. Describe what life in the Soviet Union will be like fifty years from now, lets say at the time of the ninetieth anniversary of the Great Socialist October Revolution.

That meant in 2007.

The book written by Mikhail Hvastunov and Sergei Gushchev, the journalists working for Komsomolskaya Pravda, is called Report from the Twenty-First Century. The authors wrote that we would use electronic brains on a daily basis (nowadays we call them computers), miniature transmitting and receiving stations (mobile phones) and biblio-transmission (i.e. the Internet), open cars from a distance (with remote control), take photographs with an electric camera (digital) and watch satellite television on flat screens.

They wrote about it at a time when in the house where I was born there was not even a black-and-white television set, a toilet or a phone to call the doctor.

Hvastunov and Gushchev spent most of their time in the Moscow laboratories of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, and from there they made a mental journey into the future, setting off for Siberia in the year 2007 in a wonderful jet plane.

I decided to give myself a fiftieth birthday present, which was to travel with this book right across Russia, from Moscow to Vladivostok. But I wouldnt take the plane like Hvastunov and Gushchev. Id already been there several times by train.